It's been a while since I added to my Camera Works series, an ongoing batch of blog posts explaining why still cameras operate as they do. The idea of the series is to provide background on how film and digital cameras function, so you can use that knowledge to make better pictures.

It's been a while since I added to my Camera Works series, an ongoing batch of blog posts explaining why still cameras operate as they do. The idea of the series is to provide background on how film and digital cameras function, so you can use that knowledge to make better pictures.

My only qualifications are that I've been an enthusiastic amateur photographer most of my life, some people like the photos I take, and often enough they ask me questions about the subject. Today's topic comes from a Facebook question, which was:

What is the best method/lens/settings to capture fast moving sports action without any blurring of the subject?

While some artistic blurring may occasionally be useful, that is the goal of most sports and action photography: capturing a sharp image of the subject, without blur. And to do that, you really need a digital SLR (DSLR), not a point-and-shoot pocket camera. Whether you're talking a kids' soccer match, a professional basketball game, or an airshow, a DSLR (with a long lens) gives you the best chance of good photos. Manufacturers and sales reps may claim otherwise, but they're wrong.

Why you need a DSLR—even a cheap one

Today's pocket camera models are incredibly small and convenient, and can take very good video as well as beautiful still shots in many circumstances where their subjects aren't moving much. However, for action, even a top-of-the-line point-and-shoot—like the Canon G12 or Panasonic LX5—can't compete well with the cheapest DSLRs—like the Nikon D3100, Canon XS, Pentax K-x, or Sony A390. Point-and-shoot big-lens "zuperzooms" don't do much better either, even though they're almost the same size and weight as an SLR.

Moreover, today's low-end DSLRs cost about the same (in the $500–600 range, with lens) as high-end pocket cameras. DSLRs generally offer faster and more accurate autofocus, a much wider range of lens choices, better LCD screens, proper optical viewfinders, higher shutter speeds, better low-light performance, faster shot-to-shot burst modes, better battery life, and more accessories. The main advantage of point-and-shoot cameras is that they're smaller and lighter, so you're more likely to carry them with you all the time, and they're better at taking high-quality video more easily (something no DSLRs did at all until a couple of years ago).

If you're planning to take photos of a sporting event, it's best if you plan to bring a bigger and heavier camera along, so go for the DSLR. Almost any DSLR. If your budget is really limited, a used DSLR like an older Nikon D40 or Canon Rebel XT via eBay, Craigslist, or your local camera shop's used department will still probably work better than a new cheaper point-and-shoot. You could even try for a used professional sports DSLR from earlier last decade, which would have cost thousands new but which will have depreciated drastically now, though the cost-benefit tradeoff gets trickier there.

Choose a long lens—nearly any long lens

Especially when working on relatively close-up sports, such as basketball, professional sports photographers tend to use a fast (and expensive) zoom like a Canon or Nikon 70-200 mm f/2.8. For other sports where the action is farther away, they'll choose even more expensive fast-aperture super-telephotos like 300, 400, or 500 mm f/4 lenses, or insanely pricey multi-thousand-dollar 300 or 400 mm f/2.8 glass, often with teleconverters to extend the focal length of the lens further. With those big lenses, a monopod (not a tripod) becomes essential for vertical stability and to take the weight off your shoulders, while still giving you enough flexibility to move around.

However, if you're a normal person and can't afford those, in bright light, particularly outdoors, regular telephotos and zooms that extend to 200 or 300 mm or more (even inexpensive ones) can do great. Nikon's 55-200 mm kit zoom is cheap as dirt and works great, for instance, though you'll be at f/5.6 at the telephoto end of that. I have a similar plastic-bodied 80-200 mm lens. Newer lenses with an "ultrasonic" or "silent wave" autofocus motor inside the lens are generally a bit faster to focus than older AF lenses (which may include a louder, more traditional motor or use a screw-drive motor in the camera body), but that's not always true. A monopod is still good no matter which telephoto or zoom you choose.

Fast shutter speed at almost any cost

The key thing in any action photography is to run in shutter-priority ("S" or "T") mode and to keep your shutter speed as fast as you can manage it. The old rule of thumb is 1/[focal length], i.e. at 300 mm you need 1/300th of a second or faster, but even that is for still subjects. You need faster for sports: if you can run at 1/1000th of a second or faster, and make sure you pan along with the action, you'll have the best chance of good shots.

Consumer-focused DSLRs usually include a Sports preset (with a little "running man" icon) that tries to do that for you. Relatively slow sports like curling, tennis, soccer, football, baseball, or even track and field, will do fine with those settings, whether you use Sports mode or set shutter priority fairly fast. If you're getting into horse racing, motor sports, or airshows or something, high shutter speed is even more critical.

You may have to boost your camera's ISO/light sensitivity to make that happen in any sport, since it's better to have a sharp shot and some high-ISO grain than a blurry shot with less grain. (Your camera's Auto ISO setting will do that automatically in shutter-priority or Program mode, I think, but you may need to tweak the settings to get it to do what you want.)

Also make sure to use your motor drive/burst mode at its fastest setting, and set your autofocus to Continuous, so that it will follow your subject as best it can. Fire off lots of shots. Some of them will be good and in focus, some won't, but you should get some you can work with. Be prepared to crop them later too if that will get you better framing.

Working with your camera

Full-time sports pros spend tens of thousands of dollars on lenses and thousands more on pro DSLR bodies like the Nikon D3s or Canon EOS 1D Mark IV: those are expensive, huge, heavy high-speed SLRs optimized for low-light performance, blistering autofocus and burst-mode speeds, and resilience to getting bumped around and rained on. But Nikon, Canon, Sony, Pentax, and others now make prosumer cameras that are also pretty close to the pro models in performance, while pro-grade features from a few years ago have trickled down to entry-level DSLRs today.

No matter what camera you have, you can adjust settings to get the best results possible within its limitations. If you have an older DSLR, its high-ISO and Auto ISO, burst speed, and autofocus performance might not be as good as some newer models (even some cheaper newer models!). If you don't have an SLR but instead a point-and-shoot, you might be yet more limited in how far the lens can zoom, how fast the shutter can fire, how quickly you can get a burst of shots, and how well the sensor performs when its ISO is boosted.

No matter what, though, if you buy a monopod, go as telephoto and wide-aperture as you can afford, set high speeds in shutter priority and burst mode, track your subject by panning with it as it moves, and keep the autofocus in continuous-tracking mode, you'll get the best results you can with your camera. With those things in mind, your main task is to be there with your finger on the shutter release when the magic moments occur, to capture them before they're gone.

Previously in my Camera Works series

- Introduction: learn how your camera works

- Focal length, wide angle, and telephoto

- An aperture teaser and a full article about f-stops and depth of focus

- Crop factors and "full frame"

- Shutters, flashes, and sync speed

- Intermediate f-stops

- Why "digital" lenses are cheaper

- Image stabilization, vibration reduction, and anti-shake

- Pictures that tell a story

- Get better with your modern camera by going back to 1978

- Fireworks and other night photography without a tripod

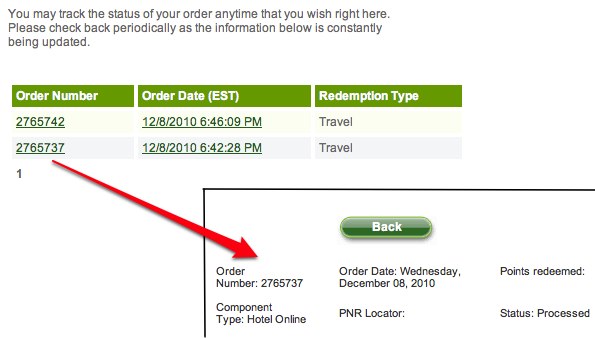

While my wife and I have had the occasional difficulty with it over the years, I like our credit union,

While my wife and I have had the occasional difficulty with it over the years, I like our credit union,