Penmachine

23 April 2010

Geek office cleanout redux

Almost five years ago, I cleaned out a bunch of old electronics and cardboard from my office/studio downstairs. Yesterday, Earth Day, I got started on it again, this time shipping out four old CRT monitors, two printers, two desktop Macs, an old PowerBook, a couple of keyboards, a scanner, an external CD-ROM drive, a broken camcorder, and a whole mess of wires:

I had an incentive to do it today because, on her way to work, my wife Air noticed a one-day Earth Day electronics recycling event at Killarney Secondary School, which is where I took the heap. It was gone in less than five minutes.

My happiest discard was a drawer full of particularly beige SCSI cables, adapters, and terminators. If you've grown up connecting things to computers with USB or FireWire or Ethernet cables, or using Wi-Fi, be thankful you didn't have to deal with SCSI and its predecessors, which often required flipping tiny switches, swapping cables around, adding thick cable terminators to devices in apparently random combinations, and fiddling with software—and still often didn't work right. Good riddance, SCSI cables:

I felt like Perseus with the head of Medusa there. And yes, I reformatted my hard disks before donating them.

Labels: apple, geekery, green, home, memories, school

15 April 2010

Sunny days at Camp Jubilee

I can almost see the place where my daughter Marina slept last night, and will again tonight. But not quite. She and her school classmates in grades 6 and 7 are at Camp Jubilee for a two-night, three-day outdoor education adventure.

I can almost see the place where my daughter Marina slept last night, and will again tonight. But not quite. She and her school classmates in grades 6 and 7 are at Camp Jubilee for a two-night, three-day outdoor education adventure.

The camp sits near the tiny shoreline community of Frames Landing (which I'd never heard of until I looked it up just now) on the west shore of Indian Arm, the fjord whose mountain boundaries I can see from my front window. But those mountains are so steep and packed together that, though the camp is closer to our house than the ski slopes of Grouse Mountain that we can see clearly every day, it is entirely hidden behind several tree-coated ridges.

The only way to reach Camp Jubilee (or the homes at Frames Landing) is by boat. The camp has one to ferry visitors back and forth from Deep Cove, the urban harbour about 15 minutes to the south that is the easternmost part of North Vancouver. The kids have been incredibly lucky this week: the weather has been sunny and unusually warm, and looks to remain so through tomorrow when they come back.

I'm sure they've had a great time, and Marina will be pooped when I pick her up at school in the afternoon. Her younger sister will be returning from her own day trip with her classmates snowshoeing on Grouse Mountain. I expect they'll be a couple of sleepy girls come Friday night.

Labels: environment, family, school, vancouver

15 March 2010

Studying for jobs that don't exist yet

After high school, there are any number of specialized programs you can follow that have an obvious result: training as an electrician, construction worker, chef, mechanic, dental hygienist, and so on; law school, medical school, architecture school, teacher college, engineering, library studies, counselling psychology, and other dedicated fields of study at university; and many others.

But I don't think most people who get a high school diploma really know very well what they want to do after that. I certainly didn't. And it's just as well.

At the turn of the 1990s, I spent two years as student-elected representative to the Board of Governors of the University of British Columbia, which let me get to know some fairly high mucky-muck types in B.C., including judges, business tycoons, former politicians, honourees of the Order of Canada, and of course high-ranking academics. One of those was the President of UBC at the time, Dr. David Strangway.

In the early '70s, before becoming an academic administrator, he had been Chief of the Geophysics Branch for NASA during the Apollo missions—he was the guy in charge of the geophysical studies U.S. astronauts performed on the Moon, and the rocks they brought back. And Dr. Strangway told me something important, which I've remembered ever since and have repeated to many people over the past couple of decades.

That is, when he got his physics and biology degree in 1956 (a year before Sputnik), no one seriously thought we'd be going to the Moon. Certainly not within 15 years, or probably anytime within Strangway's career as a geophysicist. So, he said to me, when he was in school, he could not possibly have known what his job would be, because NASA, and the entire human space program, didn't exist yet.

In a much less grandiose and important fashion, my experience proved him right. Here I am writing for the Web (for free in this case), and that's also what I've been doing for a living, more or less, since around 1997. Yet when I got my university degree (in marine biology, by the way) in 1990, the Web hadn't been invented. I saw writing and editing in my future, sure, since it had been—and remains—one of my main hobbies, but how could I know I'd be a web guy when there was no Web?

The best education prepares you for careers and avocations that don't yet exist, and perhaps haven't been conceived by anyone. Because of Dr. Strangway's story, and my own, I've always told people, and advised my daughters, to study what they find interesting, whatever they feel compelled to work hard at. They may not end up in that field—I'm no marine biologist—but they might also be ready for something entirely new.

They might even be the ones to create those new things to start with.

Labels: biology, education, memories, moon, school, science, vancouver, work

07 September 2009

Under reconstruction

Like other children across the continent, my daughters return to school tomorrow. I'm hoping the school is ready for them.

Like other children across the continent, my daughters return to school tomorrow. I'm hoping the school is ready for them.

All during the 2008–2009 school year, construction crews performed a seismic upgrade to the building. The school district set up some portable classrooms on the upper field, and the kids rotated through using them while different classrooms in the structure were rebuilt. By June, the crews seemed to be finishing up, reaching the last class.

But then, over the summer, the building was further gutted, and even this past week there were still heaps of construction materials fenced off in the schoolyard. Old light fixtures littered the grounds and interior, the gym was filled with workers and dust and mess, and there were ominous pits dug here and there.

The men have been working furiously, including Saturdays, to get the school ready for tomorrow's onslaught. I'm sure there was a lot of overtime paid this Labour Day weekend. Yet I'll be interested to find out what state the school is in tomorrow. Maybe they worked some miracles.

Labels: construction, family, holiday, school, vancouver

20 May 2009

Ouch

Okay, maybe we did pay a price for our fabulous little trip. Not because of all the heavy food, but from the intensity of the activity. Aside from our outings, we also did a bit of shopping and quite a lot of swimming in the hotel pool. So, after all that, once we got home, my cancer medication side effects kicked in and I was in the bathroom till 2 a.m.

Okay, maybe we did pay a price for our fabulous little trip. Not because of all the heavy food, but from the intensity of the activity. Aside from our outings, we also did a bit of shopping and quite a lot of swimming in the hotel pool. So, after all that, once we got home, my cancer medication side effects kicked in and I was in the bathroom till 2 a.m.

Then, this morning, we were all so wiped out we could hardly struggle out of bed. The kids were tired enough that I kept them home from school so they're in better shape for Thursday (or maybe after lunch today), and I've been resting. Alas, my wife had to make her way to a couple of medical and dental appointments, so she dragged herself out of the house.

Anyway, I think the weekend was enough of an educational experience that it's okay for the girls to miss a bit of school. The Woodland Park Zoo and the Boeing factory are a killer field trip, right?

Labels: cancer, chemotherapy, family, school, seattle, travel

28 April 2009

Healthy

It's a cliché that without health, we have nothing, but clichés exist for a reason. Here are my kids when they're healthy:

This week has been a bit of a worry because our younger daughter (top, in yellow) has been home sick for a couple of days with a vague malady (nothing like swine flu, fortunately), while yesterday, our older daughter (bottom, in fuchsia) tripped during gym class and made a total face-plant on the school gymnasium floor, leading to a doctor's visit to rule out a concussion.

(Coincidentally, two other kids also hurt themselves during the same gym class, even though they weren't doing any oddball activities—one gashed his head, the other just banged his leg and didn't have to leave school.)

Of course, I'm often laid up with side effects from my cancer medication, and this week even my wife had to ice an ankle she twisted a little while ago. So we've seen an inkling of what it could be like if we were all out of commission. I'm glad that's not the regular state, at least for the other three members of my family.

Labels: cancer, family, pain, school

04 April 2009

20 years behind the kit

Twenty years ago this spring, I played my first gig as a drummer, at the Last Class Bash for the UBC Science Undergraduate Society. Our band, the Juan Valdez Memorial R&B Ensemble, was a five-piece with me on drums, my roommates Alistair, Sebastien, and Andrew on guitars and bass, and Ken Otter (now a professor of zoology) on another guitar.

Twenty years ago this spring, I played my first gig as a drummer, at the Last Class Bash for the UBC Science Undergraduate Society. Our band, the Juan Valdez Memorial R&B Ensemble, was a five-piece with me on drums, my roommates Alistair, Sebastien, and Andrew on guitars and bass, and Ken Otter (now a professor of zoology) on another guitar.

We'd spent months rehearsing, but we still didn't know how to sing proper harmonies. Our playlist included mostly old songs from the '60s: "Gloria," "Long Cool Woman," the theme from "Batman." I skipped a final lecture for one of my high-level biology courses to set up for the show in the Student Union Building party room. Our friend Steve ran the rented PA system.

We were relatively terrible, but we were silly, and we had a good time. So did the heavy-drinking audience.

I'm still playing in a later version of the same band. Sebastien is still on guitar, I'm still on drums when I feel up to it. We're still playing some of those same songs. I've spent half my life in this act.

Labels: anniversary, band, friends, memories, music, neurotics, school

29 March 2009

Long lost friends

In 1974, on my first day of kindergarten, I made some friends. One of my earliest memories of school that year was three of us working on an art project. Rand, one of my friends, had a huge (huge for five-year-olds, at least) bottle of white glue turned upside down, but like a ketchup bottle, it was jammed.

In 1974, on my first day of kindergarten, I made some friends. One of my earliest memories of school that year was three of us working on an art project. Rand, one of my friends, had a huge (huge for five-year-olds, at least) bottle of white glue turned upside down, but like a ketchup bottle, it was jammed.

Brent, my other friend, sang out, "There's no more gluuuuuue!" And then a huge glop of it fell onto the paper, completely covering up what we were working on.

I stayed friends with Rand and Brent for many years afterward. When Brent's family took a year away to go sailing around the Caribbean, we borrowed their TRS-80 Model I personal computer, the first one we had in our house. Rand and I spent hours at each other's homes, or with his family at their cabin on Keats Island, playing with Star Wars action figures.

Even when Rand changed to a West Side private school and his family moved out that way, we kept in touch, and a couple of years later I went to that school too. We lost touch with Brent slowly after that, though he was in my Boy Scout troop until 1982, and I have seen him from time to time in the interim.

Rand and I once tried making smoke bombs at his place, and drying them in the microwave. Not a smart move. We had to open all the windows and pull out the smoke alarm battery, hoping things would clear before his parents got home.

Eventually, he moved to yet another school and, as happens, we drifted away from one another. He emigrated to New York City almost 20 years ago, got married, and had a son. I stayed here in Vancouver, got married, and had two daughters. My daughters started kindergarten at the same school where Rand and I met a few years ago. They're still going there.

Recently Rand and I got in touch again on Facebook. He and his wife and son were in town last week to visit his family, and on Friday night my girls and I met them downtown for dinner. It was a short visit, but fun—the first time Rand and I had seen each other for more than 25 years. Long enough that he had time to grow taller than me.

We were both pretty big nerds back in the '70s and early '80s. Our nerdiness has mellowed, and it's also cooler to be geeky these days than it used to be. So we're different, yet not. Just like Vancouver.

Labels: friends, memories, newyork, school, vancouver

16 March 2009

A little walk

This is my kids' walk to school—and since I attended the same school in the '70s, it's also the same walk I took each day 30 years ago:

Compiled from 47 photos taken with my Nikon D50 every 15 to 20 steps on the way, and made with iMovie '09. Music is my tune "Camp Walk," from 2006.

Labels: family, memories, movie, nikon, penmachinepodcast, school

10 March 2009

Fooling yourself

Back in 1974, Richard Feynman, one of the most famous physicists of the 20th century, gave a commencement address at the California Institute of Technology. He called it "Cargo Cult Science" (PDF). It contains what I think is the best succinct summary of the scientific process:

The first principle is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool.

Then, he said, "it's easy not to fool other scientists. You just have to be honest in a conventional way after that." The entire structure of science—in universities and journals, online and at symposia, and in the principles of being able to repeat experiments, falsify theories, and predict results—is an attempt to keep from fooling ourselves about reality.

That shows how hard it is to avoid being foolish: scientists and the rest of us still fool ourselves all the time. But the process also does a good job correcting mistakes, so our foolishness doesn't last. As a human system, science isn't perfect, but it does well at refining our knowledge, letting us weed out imperfections in what we understand about our world and universe.

Labels: publicspeaking, school, science

10 February 2009

Real cutting and pasting

Graphic designer Michael Bierut is more than a decade older than me, but still, his article in the New York Times (via Kottke) this week felt familiar. I realized that's because, even though I've only hacked around the edges of the business of design and layout, I've been doing it for more than 30 years in some way or another.

Graphic designer Michael Bierut is more than a decade older than me, but still, his article in the New York Times (via Kottke) this week felt familiar. I realized that's because, even though I've only hacked around the edges of the business of design and layout, I've been doing it for more than 30 years in some way or another.

More importantly, I belong to what is probably the last generation to straddle the gap between pre- and post-computer design. In elementary school in the 1970s, we made student newspapers with pens on Gestetner mimeograph paper, reproduced on smeary blue-inked sheets just like our notices and test papers. (More than a decade later, I had a used hand-crank Gestetner in my basement to run off newsletters for my computer club the Apple Alliance—there's some irony, or at least foreshadowing, in that.)

By the mid-1980s I was printing out long columns of dot-matrix type to cut and paste (with actual scissors and glue) onto photocopy masters, while also using Letraset rub-on letter stencils for headlines. That was for student newspapers—but putting together our high school annual still involved typewritten text, printed photos, rubber cement, and grease pencil. The real work of typography and layout was left to the professionals we never met at the printing plant in Winnipeg. We had perhaps two or three choices of typeface.

A few years later, the Science Undergraduate Society at UBC had an IBM PC clone with Ventura Publisher, and then a Mac with PageMaker. The only laser printer available was downtown, so I took floppy disks down and paid several dollars a page to print out 8x10s, which we then lined up to assemble tabloid-style layouts on blue-lined layout sheets. I drove those down to the printer to produce some of the first issues of The 432.

By the early '90s, everything was digital until the presses rolled, and a few years after that even floppies or CD-Rs were passé in favour of email and FTP. This decade I've hardly done anything for print at all: what little design work I do is for the Web, or podcasts, or maybe a PDF file that might get printed. Maybe.

So for me, a desktop, rulers, pica scales, cut and paste, cropping, and so on represent memories of the real physical activities. My kids may do some similar things for art projects, and with their grandmother when creating cards and photo books in her crafting room in Maple Ridge, but I don't expect they ever will for publication. Why would they, when we have six Macs (and two laser printers) in the house?

Labels: art, design, ego, memories, retro, school

27 January 2009

Math and photos

When you have one child, it's easy to delude yourself about the magnitude of your influence on them. When our first daughter was young, for instance, I subconsciously assumed that she was the way she was largely because of the parenting my wife and I offered. As soon as her sister was born a couple of years later, we discovered how wrong we were.

When you have one child, it's easy to delude yourself about the magnitude of your influence on them. When our first daughter was young, for instance, I subconsciously assumed that she was the way she was largely because of the parenting my wife and I offered. As soon as her sister was born a couple of years later, we discovered how wrong we were.

Not that parenting (or family, or friends, or society more generally) is irrelevant, but parents of more than one child will tell you that their kids do seem to be born with certain personality traits, and they develop their own interests and approaches to the world as they grow. Children are little people, individuals, right from the beginning, not blank slates to be molded completely by how we raise them. Our daughters have a lot in common, but they're also quite different.

Math girl

As I've noted before, my younger daughter L, who turned nine yesterday, makes up her own homework in her spare time. A couple of days ago, for example, she was copying equations out of a Math 11 textbook. She's a little too young to understand them—after all, they're eight years ahead of her current curriculum—but she's certainly getting good at writing square-root signs.

My wife Air, who's a math teacher (hence the textbooks in our house), suggested that L try the Grade 8 book instead, only five years ahead, where some of the problems might be closer to her level. So this morning we woke up to hear our daughters arguing vociferously about subtraction problems.

Photo girl

Among her other interests, our older daughter M has liked photography for some time, and we bought her a little Pentax point-and-shoot digicam for Christmas 2007. She likes it, but she also enjoys using my big Nikon DSLR because of the higher quality photos it takes. She often creates some really good compositions, and of course her perspective is quite different from mine. Here are some of my favourites she's taken:

They're certainly better than anything I took when I was ten. Or, as in the case of the top left photo, four (!).

Labels: family, photography, school

21 November 2008

Farewell, Mr. PJ

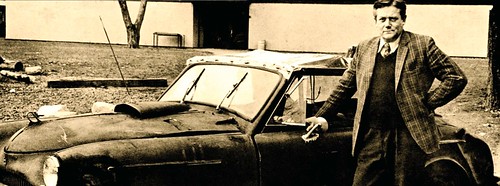

In 1986 I was in the last class of Math 12 students taught by Tony Parker-Jervis, the legendary mathematics teacher, hot-rod enthusiast, and curmudgeon at St. George's School. He had been on staff there since the '50s or early '60s—and before that, he had been among the school's first students, graduating in 1935 before going off to war, where he taught himself advanced mathematics while calculating ballistics trajectories.

In 1986 I was in the last class of Math 12 students taught by Tony Parker-Jervis, the legendary mathematics teacher, hot-rod enthusiast, and curmudgeon at St. George's School. He had been on staff there since the '50s or early '60s—and before that, he had been among the school's first students, graduating in 1935 before going off to war, where he taught himself advanced mathematics while calculating ballistics trajectories.

I just received a message that Mr. PJ has died, more than two decades after he retired. Former students like me remember him fondly, though he terrified us at the time. His ruthless high standards and eccentric teaching and testing methods are probably the main reason that I, not a natural mathematician, scored well enough in provincial exams and Euclid contests to take advanced-level freshman math courses at university. (I finally exhausted my capabilities with the brain-bending black art of integral calculus, where I squeaked by with 56%.)

It strikes me as odd now, but seemed natural at a British-style boys' school in the '80s: Mr. PJ spoke with a distinct, growly English accent. That's strange because he grew up here in Vancouver. He also smoked relentlessly, wore chalk-stained tweed jackets (or maybe the same jacket?) every day, and was infamous for keeping underperforming students after school for short tests he made up on the spot. He called them GOWYGIAR—Get Out When You Get It All Right. We pupils could help each other as he sat at his desk or paced the room threateningly, but each of us could only leave when we had answered every question to his satisfaction. Sometimes they were long afternoons.

UPDATE: His British accent is more sensible now that I know that in addition to being born in Singapore and spending his first few years on a Malaysian rubber plantation (which I had heard before), he studied in England after living in Vancouver, before the War (which I had not). The new details are from his obituary, published in the Vancouver Sun.

Our raw marks in his classes were pitiful, because his tests and assignments were so hard that all but the most gifted boys routinely averaged 30 or 40%. But he scaled up our scores by some inscrutable formula that usually bumped the best marks—maybe as high as 70%!—up to 100%, dragging the rest of us along. He chuckled wryly at that, but he taught us enough that provincial exams seemed easy.

Mr. PJ drove a massive '70s Cadillac, but his secret weapon was an old Austin (British car, of course) that he had souped up himself with a huge V8 engine and bizarre silver paint. Rumours had it capable of well over 150 miles an hour. I'm not sure what he did to the Austin frame to keep it from annihilating itself at such speeds. He no longer brought it to school regularly when I was there, but we did see it occasionally. It merited its own three-page spread in The Dragon (PDF), the school newsletter, as late as last year. The article was simply called "THE CAR," and we all knew what it was talking about.

I hadn't seen or heard from Mr. PJ at all in the past 22 years, and don't even know what he'd been up to. Like other teachers who have died since I left St. George's School, including my old home room teacher Craig Newell this year, he leaves a gap that I didn't realize was there. The influence of teachers, decades later, is remarkable.

Labels: death, memories, school, teaching, vancouver

20 November 2008

Berlin 1965

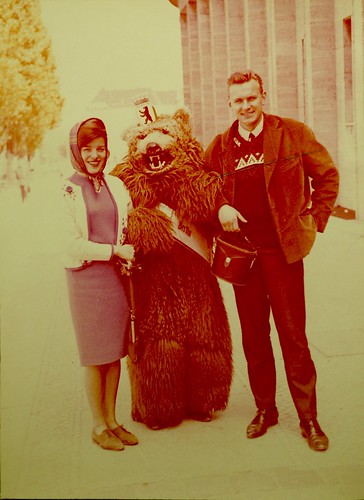

For as long as I can remember, my parents have had this photo hanging on their bedroom wall:

I made a copy last night because my younger daughter has a project at school where she's discussing Germany, and she wanted a copy of this picture to illustrate Berlin, where it was taken. It was 1965, on my parents' honeymoon. My mom and dad were 26 at the time, and that's the city's mascot, a bear, between them. Here they are today (without the bear):

My dad still wears collared shirts most of the time, though my mom isn't into the bonnets anymore.

They look young in that first photo. My wife and I were the same age, 26, when we got married 30 years later. We didn't feel so young then, but we were too.

Labels: anniversary, europe, family, photography, school

16 October 2008

Links of interest (2008-10-16):

I'm still doped up on Tylenol 3's and pretty tired post-surgery, so am not up for much thinking or original posts. I'm also contemplating email bankrupcy again, mere months after my last one, as my inbox creeps up to 800 once more. Sigh. Anyway, here's some interesting stuff:

- What if all movies had cell phones? (There's a good reason No Country for Old Men was set in 1980, by the way.)

- A worthy quote in this electional season: "I like to pay taxes. With them I buy civilization." - Oliver Wendell Holmes (though it may be a folksier recasting of "Taxes are the price we pay for a civilized society").

- "Hey news executives! Try this newsroom pop quiz: Give each staff member a pencil and tell everyone to stop what they're doing and write out the tag that creates a hypertext link." (via Dan)

- Andrew Sullivan rounds up quotes from a number of last night's press and blogger reactions to the final McCain-Obama debate.

- Also from Sullivan, it's a bit sad how well this video reflects the approach of the McCain campaign right now.

- While Leica's upcoming S2 camera is quite large (especially the lenses) for a digital SLR, it has a medium-format size sensor, meaning that it is smaller and probably more ergonomic than most of its direct competitors, and that even the rumoured €10,000–20,000 price isn't as insane as it sounds. Nevertheless, the cost of a reasonably complete S2 system when it's released next year will rival that of a condominium. It also bodes well for future "lower end" (for Leica, at least) cameras from this legendary manufacturer.

- What's it like to write other people's term papers for a living? (via Kottke)

- The web comic Basic Instructions makes me laugh almost every single time a new one comes out.

- Vancouver locals Buzz Bishop and Darren Barefoot accurately summarize the Canadian election held this week, in which nothing much changed. The result (as I discussed earlier) bodes poorly for our country's environmental and climate policy, which is one subject we can't afford to waste time on, unfortunately.

Labels: environment, film, leica, linksofinterest, movie, news, photography, politics, school, telecommunications, web, writing

09 October 2008

Grad up the mountain

It's been many years since I attended a university convocation ceremony, but I went to one today. My cousin Tarya graduated with a Bachelor's degree from Simon Fraser University, which I can see atop Burnaby Mountain from our front window.

It's been many years since I attended a university convocation ceremony, but I went to one today. My cousin Tarya graduated with a Bachelor's degree from Simon Fraser University, which I can see atop Burnaby Mountain from our front window.

I was glad to be able to make it, before my surgery tomorrow. (I've been on a liquid diet all day, so I had to miss out on the family lunch afterwards.) It's been almost 20 years since I graduated from UBC, and Tarya's the first in our family to get a university degree since then—and since I'm an only child, my cousins are as close to siblings as I have. She and her longtime boyfriend T.J. also just announced their engagement too, so it's an exciting month for her.

Exciting for many of us, in fact. My next excitement is that I'll be in hospital for most of the next week, so don't expect much in the way of updates here.

Labels: family, school, surgery

23 September 2008

Better social environments in school

My two kids attend the same elementary school I did 30 years ago. Although there is a recent addition, constructed since my older daughter began there in 2003, plus some ongoing seismic upgrading, the building hasn't changed much at all. (It was a relatively new structure when I started there in 1974.)

My two kids attend the same elementary school I did 30 years ago. Although there is a recent addition, constructed since my older daughter began there in 2003, plus some ongoing seismic upgrading, the building hasn't changed much at all. (It was a relatively new structure when I started there in 1974.)

It was always a good neighbourhood elementary school, but one thing that has improved dramatically is an aspect of the social environment. The first week of school has all the students in mixed classes with others of various grades: final class assignments don't come until the second week. Throughout the year, the school organizes events and regular volunteer jobs so that more senior students (grades four, five, six, and seven) mentor and support younger students (kindergarten through grade three).

The consequence is that students get to know each other across all eight class years in the school. Even in grade one, my daughter was able to wave and say hi in the hallway to grade seven students she knew. And now that she's in grade five, she has buddies in lower grades. Her sister, in grade three, knows kids both older and younger.

That's a big change from the '70s: when I started, grade seven students were scary and huge and intimidating unknowns. They remained that way pretty much until I was in a split grade six-seven class years later. And by then I had no idea who the little kids were.

I don't know if this is a common change in elementary schools in Greater Vancouver, or Canada, or more generally. Our school administration has put a lot of effort into helping students understand their peers of all ages and background. Of course there is still bullying, and fights break out, but no more (and perhaps less) than I remember. I think that overall it's more of a community than when I went there.

Labels: family, friends, memories, school, vancouver

02 September 2008

It is a new world

Included on my ten-year-old daughter's school supply list for this year:

1 USB flash memory key

The smallest and cheapest one we could find was part of a stack of them on a school supply table at Staples. 1 GB for $20, and smaller than an eraser. I think I hear the echoes of my young geeky self swooning in disbelief.

Labels: family, gadgets, geekery, memories, school

01 August 2008

Some people are way smarter

I spent my last four years of high school at St. George's, an exclusive British-style boys' school in Vancouver, and graduated in 1986. It was a good education, academically rigorous. Teachers there taught me to write, and offered me the opportunity to travel as far as Russia and Italy. But, especially after returning for a day with one of my daughters for my 20th reunion in 2006, something seemed amiss—aside from the obvious absence of girls. Jen's recent post about her 10th high school reunion got me thinking about my uneasiness again.

A recent article in The American Scholar called "The Disadvantages of an Elite Education" (via Jason Kottke) put a finger on it. The article focuses on America and its elite education system, the high-end elementary and high schools that feed into universities and later exclusive business and political organizations. Here's how author William Deresiewicz starts out:

It didn’t dawn on me that there might be a few holes in my education until I was about 35. I’d just bought a house, the pipes needed fixing, and the plumber was standing in my kitchen. There he was, a short, beefy guy with a goatee and a Red Sox cap and a thick Boston accent, and I suddenly learned that I didn’t have the slightest idea what to say to someone like him. So alien was his experience to me, so unguessable his values, so mysterious his very language, that I couldn’t succeed in engaging him in a few minutes of small talk before he got down to work.

That's what I sensed in part while I was at my Canadian elite school too, even though I wanted to be there. It was what really struck me 20 years later: how isolated, inward-looking, and self-congratulatory it is (and was) as an institution. While it certainly has outreach programs and encourages students to travel and be charitable and so on, it's easy to graduate feeling entitled to something, or everything.

And it can be something of a shock to go into a big public university, as I did, and find out just how many people are way, way smarter than you, in all sorts of ways. Then to discover, beyond that, those who are smarter and more creative and more interesting still, but who never went to university at all.

St. George's has always been a very good school—and it's happy to tell you so. But, as in Deresiewicz's Yale University:

Only a small minority [of students] have seen their education as part of a larger intellectual journey, have approached the work of the mind with a pilgrim soul. These few have tended to feel like freaks, not least because they get so little support from the university itself [which is] not conducive to searchers.

I'm no great intellectual vagabond, but seeing a bigger world beyond academics or business or law or medicine has been important to me. The most impressive, and the smartest, people I've met have been those who flourished outside the educational and business elites my high school was part of.

There's a tradition at private schools that encourages generations to attend, as part of a true Old Boys' network: students grow up, and then send their own kids, who later send theirs. But even if I had sons instead of daughters, I don't think I'd send them to my old high school. Which is a bit sad.

Labels: family, memories, school

19 June 2008

The green bog

I accompanied my older daughter's school field trip to Burns Bog in Delta, south of Vancouver, today. We had fun, and managed to avoid any heavy rain.

I accompanied my older daughter's school field trip to Burns Bog in Delta, south of Vancouver, today. We had fun, and managed to avoid any heavy rain.

I also took the chance to create some more high dynamic range (HDR) photos. That involves taking three or more pictures at different exposures, and then combining them in software using a technique called tone mapping.

You can see what that does below.

On the left you can see my camera's calculated single optimum exposure, the "best pick" the camera would normally make. Nothing wrong with it. But on the right is the HDR version I created, combining the left-side exposure with two others, one brighter and one darker:

The extra vividness of colour I chose to put into the tone-mapped HDR is obvious, but if you examine the large version, you can also see a lot more detail in the shadows and highlights of the image. That's the high dynamic range we're talking about—in a normal photo, some of the shadows might be totally black, while some of the highlights might be blown out to total white.

Tone-mapped HDR photos involve a lot more decision making than traditional pictures, because depending on how you manipulate the image, its appearance can vary widely, from slightly enhanced (the way filters and darkroom work used to punch up film images) to strangely surreal (more like cross-processed, solarized, or otherwise highly altered film images).

So far I've been photographing nothing but plants in HDR for some reason, but I will play with the technique some more and post additional pictures to my Flickr HDR set.

Labels: geekery, hdr, park, photography, school, vancouver

17 May 2008

It was acceptable in the eighties

Back in 1986, a group of kids from my all-boys' private school (St. George's School in Vancouver) and a couple of affiliated girls' schools (Crofton House and York House) took a Spring Break "art tour" trip to Italy, with whirlwind visits to Rome, Florence, Pisa, Venice, Turin, and so on.

I have photos in an album somewhere, but Anne Pewsey Richards, who was also on the trip, has done much better. She posted a bunch of pictures to Facebook, and gave me permission to repost them at Flickr. If you thought my glasses were big the year before in my geekiest photo, check them out here with the accompanying sunglass clip-ons:

Anne's group shot also includes some prime '80s hair and fashions. (I'm on the far right, squinting—shoulda worn the clip-ons.)

Finally, you can see that I was a camera nerd, with the Nikon, big zoom lens, and obnoxious camera strap, even then (again, I'm far right—guess I had the contact lenses on there):

I'm sure there was no way at all that local Italians could tell that we were tourists. There are several people in her photos (Anne included—but she noted that she's lived in England since the early '90s) whom I have not seen even once in the intervening 22 years.

I also haven't been back to Europe since this trip.

Labels: europe, friends, memories, photography, retro, school, travel

16 March 2008

Wacky wireless

I'm posting this from my iPod Touch on a bench at the playground at my kids' school. They are riding bikes. Yay for free open Wi-Fi from one of the nearby apartments.

Labels: apple, family, geekery, ipod, school

15 March 2008

Links of interest for the Ides of March (2008-03-15):

- I mentioned the other Derek Miller before. Looks like he's going to get even more famous—his latest album is a collaboration with Double Trouble and Willie Nelson. So when you see "Derek Miller with Willie Nelson," it's really not me.

- I didn't know that the Milky Way, in which we live, is a barred spiral galaxy.

- User interface design, simplified.

- "That's not the same." "Yes it is."

- I love the existentialism of Garfield Minus Garfield.

- The 20 biggest record company screw-ups of all time.

- Podcasting statistics, explained.

- Check out the iPod on the Space Shuttle. (They had to put in a different battery for safety, by the way.)

- From Stuff White People Like: "[Going to graduate school] is an opportunity to join an elite group of people who have a passion for learning that is so great they are willing to forgo low five-figure publishing and media jobs to follow their dreams of academic glory."

Labels: ipod, linksofinterest, music, podcast, school

14 March 2008

Probability, the Fab Four, and my kids

As always, there are some people who think those darned kids today are taking us all to hell in a handbasket with their ignorance and filthy habits. However, I seem to recall titles like this only in my university statistics course textbook:

But that's not where it comes from. It's a school math worksheet for my younger daughter, who is eight and in grade two. I'm not sure "data management and probability" were words I could even say at that age. (Then again, I did know what "carbon monoxide" was from my first favourite book.)

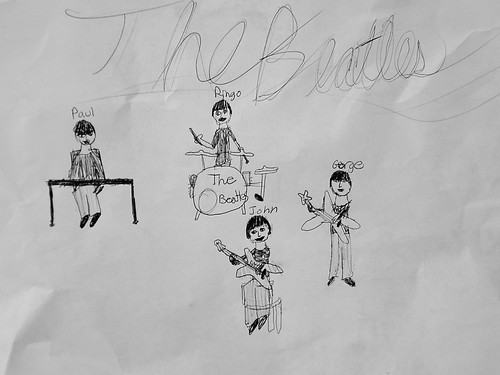

As for my other daughter, who is ten, she drew a picture the other day. It's taped to her bedroom door:

I liked the Beatles at that age too, but she loves them. I had no idea who the individual Beatles were, never mind what instruments they played—especially that Paul played piano as well as bass.

Notice that while John and George are playing their guitars left-handed, which isn't correct, Ringo's drums are frighteningly accurate. And even though his kit didn't have one, hers has a soundhole in the front drum head as most do these days. I guess my work as a drummer has rubbed off a bit.

Kids today. Too damned smart.

Labels: age, band, family, neurotics, probability, school

09 March 2008

Links of interest (2008-03-09):

- "You call this traveling? Twenty-one days, 15 countries, 45,000 miles—without setting foot outdoors."

- "The more affluent a country gets, the more things parents come to see as essential for raising children [so] as long as the world keeps creeping out of poverty, families will continue to shrink."

- jamNOW lets you jam online with other musicians, interact with fans, and listen to live streams from nightclubs all over the place. Haven't tried it, so I'm not sure how well it works.

- Looks like the iMac DV in our kitchen is finally officially obsolete. It's slow, but it still works pretty well.

- Are things really this bad for biology teachers in significant portions of the U.S.A.?

- "If all you do is work, your value judgements are unlikely to be sound."

- "I rejoice in this life that I have, and in the grandeur of a world that preceded me, and an earth that will abide without me."

- "Studies have shown that abstinence-only education does virtually nothing to prevent kids from having sex [and that] abstinence-only group[s] used birth control less frequently."

- "When I get a resume, the first thing I do is type the person's name into Google. If nothing comes up, I trash the resume without reading it."

- "I don't want my ISP looking at how I use the Internet to target ads to me, period, any more than I want the phone company listening in on my conversations in order to sell me stuff."

- TripIt looks like one of the best online travel resources out there, though I haven't tried it.

- How to make your website or blog faster.

- The Universe is 13.73 billion years old, give or take only about 120 million years. Now that is a cool finding.

Labels: apple, astronomy, evolution, family, google, linksofinterest, music, school, science, sex, space, travel, web

05 March 2008

VFS students made a video of my tsunami blog posts

Back in late 2004 and early 2005, following the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, I wrote a series of blog posts that turned into a popular online article about tsunamis.

Back in late 2004 and early 2005, following the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, I wrote a series of blog posts that turned into a popular online article about tsunamis.

Now a two-minute video based on it, created by three local film school students, is available in iPod-compatible format for iTunes or QuickTime—as well as on my podcast.

Click the preview below to play it, or the direct link to see it bigger (that big one is a 25 MB MPEG file, so it may take awhile to load):

My friend Sebastien, who is Head of Digital Design at Vancouver Film School, referred me to the three students (Jamie Peterson, Erica Edwards, and Shalinder Matharu), who needed a topic for an infographic project. My contribution was limited to a couple of basic scripts; they did the rest, adapting the article into the instructional video graphic using Adobe Illustrator, Photoshop, and After Effects (no, those are not real paper cutouts—I asked).

Obviously, they had to cut down the concepts a huge amount to fit into the short time available, but I think the result is effective. It's difficult to keep scientific accuracy in such an abbreviated format, but I believe any quibbles a real wave researcher might have (such as with the shape of the wave) are pretty minor. Nice job, Jamie, Erica, and Shal.

Labels: animation, blog, podcast, school, science, video

21 December 2007

Happy Solstice

Here's a photo of the sun finally lighting up the wall of my daughters' school this morning. It was 8:53 a.m.—there's the Winter Solstice for you:

Labels: family, holiday, school, science, weather

10 November 2007

Worth remembering

I went to St. George's School, a private boys' high school in Vancouver. It was founded in the early 1930s, so many of the school's first graduates fought in World War II. Quite a number of them died.

I went to St. George's School, a private boys' high school in Vancouver. It was founded in the early 1930s, so many of the school's first graduates fought in World War II. Quite a number of them died.

Each year on Remembrance Day, November 11 (even if it falls on a weekend, as it does tomorrow), the school holds a large service where the names of those dead former students are read out. It takes some time.

My daughters' public elementary school, Chaffey-Burke in Burnaby, also used to be my school, from kindergarten through grade seven. It held its Remembrance Day assembly yesterday, and I attended. The school was built in the late '60s, so none of its former students are veterans of the big wars, but the assembly was still a significant event. The staff work hard to make the remembrance something real, not a simple reciting of platitudes.

As part of the event, the school invited Mr. Tom Stewart, a local World War II veteran, to attend and speak. He brought a photo of himself as a boy in uniform, before he set out to fight, and reminded the students that kids like the one he was, teenagers not that much older than the pupils themselves, not only went off to Europe and the Pacific then, but are doing just as hard and dangerous a job in Afghanistan now. The military, he said, doesn't decide to fight—those are political choices—but youngsters are always the ones hired to do the work, to risk injury and death.

As they filed from the gym, each student shook his hand—many in a rush to get some lunch, but some with genuine appreciation.

Canada treats Remembrance Day pretty seriously, even though we haven't had a drastic war on our own soil. The carnage of World War I in Europe, which inspired the day, changed the demographics and politics and character of this country irrevocably. And Canadian coffins flown back regularly this year from Central Asia remind us that despite what we should have learned from all the horrors of the 20th century, peace is a long way off for many people in the world—ourselves included.

I've always treated Remembrance Day pretty seriously too, in part because of that list of names of my distant high-school colleagues. More so this year, as I face my own thoughts of death. Even a hardened cynic would find it pretty hard to hear 400 poppy-wearing little kids singing "Where Have All the Flowers Gone?" and not get a bit choked up. Especially when they start singing it again spontaneously at the end of the ceremony, long after they were supposed to be finished.

Labels: death, family, holiday, remembranceday, school, war