Penmachine

30 March 2010

Crime, sin, and authority

I've tried to figure out why the escalating sex abuse scandal in the Catholic Church is making me so angry. I mean, there's the obvious stuff: some priests and other Church officials have been getting away with the rape and beating of children for decades. And much of the Church hierarchy and bureaucracy, including the man who is now Pope, has been working hard to cover it all up, often with the tacit assistance of governments and other civil authorities.

A few of my friends and acquaintances are Catholics, but as far as I know none of them have been victims of these monsters—which is a relief. And I'm not only not Catholic, I'm not Christian or religious at all, but a happy atheist. However, I'm not gloating about the Catholic scandals, in some sort of twisted "I told you so" way. I'm sad and viscerally infuriated, in a way I hope many Catholics are, and quite a few do seem to be. Occasionally, learning new details makes me want to vomit. (Then again, that's not hard to do in general these days.)

I think my fury is it's because it's been going on for so bloody long: not just the physical and sexual abuse, but public knowledge of it and Church inaction about it. More than 20 years ago, following the Mt. Cashel Orphanage sex-abuse scandal in Newfoundland, a friend of mine and his girlfriend (who weren't afraid of being a bit tasteless) came to a Halloween party dressed as a priest and an altar boy, respectively. Even in the 1980s, the concept of a molesting priest was so widespread that everyone at the party got the reference.

It's also been 12 years since the Canadian federal government began attempts to apologize for sexual and physical abuse of native students at residential schools run by the Anglican, United, and Roman Catholic churches across the country until the 1960s, and to compensate the victims financially. And that's just here in Canada.

There are, unfortunately, small proportions of sexual predators and sadists in positions of authority inside some institutions that care for children, including schools, hospitals, foster homes, summer camps, and so on—and also including churches and religious organizations outside Catholicism. And sometimes there are coverups. But once exposed, those coverups can, should, and usually do result in shame, dismissals, apologies, and criminal charges. Even decades after the events.

Many groups and individuals within the Roman Catholic Church have had integrity, trying to get the molesters fired, charged, and punished. Yet men of authority within the institution, throughout its hierarchy—from priests and bishops to archbishops, cardinals, and apparently right up to the Pope—have used its power, influence, and worldwide reach to deny, deflect, hide, obfuscate, and in many cases abet those of its members who abuse children.

Their priority seems to have been to protect their Church, and the pedophiles within it, at the expense of their victims, the most vulnerable and innocent of its billion members. When pressed by incontrovertible evidence and public pressure, those same authorities have released half-hearted and defensive apologies. The situation is abominable, and the scandal deserves to be global front-page news, as it has become in recent months.

The Catholic Church claims to be the highest possible moral authority on Earth. Of course, personally, I think that's ridiculous. The horrifying enormity of child abuse and coverup within the Church over decades—more likely centuries, if we're honest with ourselves—only reinforces my conviction.

Indeed, it's hard to think of crimes more vile. If the beating and rape of children—as well as covering up those acts and enabling them to continue—are not sins worthy of excommunication, and presumably hellfire in the afterlife, I don't understand what could be. So if Catholics intend to continue taking claims of moral authority seriously, they must demand some large-scale changes in their Church, and the Pope and his underlings must listen to and act on those demands.

Given the glacial pace of change in Rome, and the stupefying weight of dogma and doctrine and history, I'm not optimistic. But I also genuinely hope that I am wrong.

Labels: controversy, linkbait, news, politics, religion, sex

05 January 2010

Death, pessimism, and realism

I've mused about death often enough on these blog pages, especially since I developed cancer in 2006 and it spread into my lungs since 2007, and now that it's gotten worse. I've also discussed my atheism and how that affects my attitude about death.

Some people think that without any belief in an afterlife, or a soul, or Heaven, death for me must be a scarier or emptier than for those who believe in such things—that somehow I must face death without comfort or solace. But that's not true. I have tried to explain it before, but yesterday blogger Greta Christina did a better job. She calls it "the difference between pessimism and realism," and it's worth a read, whatever you believe.

Labels: cancer, controversy, death, religion

06 November 2009

Raising free-thinking kids

(Cross-posted from Buzz Bishop's DadCAMP.)

Back in the mid-1970s when I grew up in Vancouver, almost all the stores were closed on Sundays, because of a piece of legislation called the Lord's Day Act. Every day before class in elementary school, we said the Lord's Prayer. These were vestiges of a general assumption, made since British Columbia was colonized a century earlier: even if everyone in B.C. wasn't Christian, the province would still run as if they were.

But Metro Vancouver has become remarkably secular in the three decades since then. In the 2001 Census, 40% of the population identified itself as having "no religious affiliation," and the proportion is probably even bigger now. (That's two and a half times the average across Canada.) My wife and I fit the trend: we have raised our two daughters, ages 9 and 11, in a non-religious household. Like us, few of our friends attend a mosque, temple, or church.

Buzz asked me to write this post because he saw that I just joined the Facebook group for Parenting Beyond Belief, a website run by Dale McGowan from Atlanta, Georgia. I signed up not because I needed much advice about raising children without religion (something many of us now do, especially in Vancouver), but to note publicly that it's been the approach in my family since our kids were born.

[Read more at dad-camp.com...]

Labels: canada, family, history, religion, vancouver, web

28 October 2009

Evolution book review: Dawkins's "Greatest Show on Earth," Coyne's "Why Evolution is True," and Shubin's "Your Inner Fish"

Next month, it will be exactly 150 years since Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859. This year also marked what would have been his 200th birthday. Unsurprisingly, there are a lot of new books and movies and TV shows and websites about Darwin and his most important book this year.

Next month, it will be exactly 150 years since Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859. This year also marked what would have been his 200th birthday. Unsurprisingly, there are a lot of new books and movies and TV shows and websites about Darwin and his most important book this year.

Of the books, I've bought and read the three of the highest-profile ones: Neil Shubin's Your Inner Fish (actually published in 2008), Jerry Coyne's Why Evolution is True, and Richard Dawkins's The Greatest Show on Earth: The Evidence for Evolution. They're all written by working (or, in Dawkins's case, officially retired) evolutionary biologists, but are aimed at a general audience, and tell compelling stories of what we know about the history of life on Earth and our part in it. I also re-read my copy of the first edition of the Origin itself, as well as legendary biologist Ernst Mayr's 2002 What Evolution Is, a few months ago.

Why now?

Aside from the Darwin anniversaries, I wanted to read the three new books because a lot has changed in the study of evolution since I finished my own biology degree in 1990. Or, I should say, not much has changed, but we sure know a lot more than we did even 20 years ago. As with any strong scientific idea, evidence continues accumulating to reinforce and refine it. When I graduated, for instance:

- DNA sequencing was rudimentary and horrifically expensive, and the idea of compiling data on an organism's entire genome was pretty much a fantasy. Now it's almost easy, and scientists are able to compare gene sequences to help determine (or confirm) how different groups of plants and animals are related to each other.

- Our understanding of our relationship with chimpanzees and our extinct mutual relatives (including Australopithecus, Paranthropus, Sahelanthropus, Orrorin, Ardipithecus, Kenyanthropus, and other species of Homo in Africa) was far less developed. With more fossils and more analysis, we know that our ancestors walked upright long before their brains got big, and that raises a host of new and interesting questions.

- The first satellite in the Global Positioning System had just been launched, so it was not yet easily possible to monitor continental drift and other evolution-influencing geological activities happening in real time (though of course it was well accepted from other evidence). Now, whether it's measuring how far the crust shifted during earthquakes or watching as San Francisco marches slowly northward, plate tectonics is as real as watching trees grow.

- Dr. Richard Lenski and his team had just begun what would become a decades-long study of bacteria, which eventually (and beautifully) showed the microorganisms evolving new biochemical pathways in a lab over tens of thousands of generations. That's substantial evolution occurring by natural selection, incontrovertibly, before our eyes.

- In Canada, the crash of Atlantic cod stocks and controversies over salmon farming in the Pacific hadn't yet happened, so the delicate balances of marine ecosystems weren't much in the public eye. Now we understand that human pressures can disrupt even apparently inexhaustible ocean resources, while impelling fish and their parasites to evolve new reproductive and growth strategies in response.

- Antibiotic resistance (where bacteria in the wild evolve ways to prevent drugs from being as effective as they used to) was on few people's intellectual radar, since it didn't start to become a serious problem in hospitals and other healthcare environments until the 1990s. As with cod, we humans have unwittingly created selection pressures on other organisms that work to our own detriment.

...and so on. Perhaps most shocking in hindsight, back in 1990 religious fundamentalism of all stripes seemed to be on the wane in many places around the world. By association, creationism and similar world views that ignore or deny that biological evolution even happens seemed less and less important.

Or maybe it just looked that way to me as I stepped out of the halls of UBC's biology buildings. After all, whether studying behavioural ecology, human medicine, cell physiology, or agriculture, no one there could get anything substantial done without knowledge of evolution and natural selection as the foundations of everything else.

Why these books?

The books by Shubin, Coyne, and Dawkins are not only welcome and useful in 2009, they are necessary. Because unlike in other scientific fields—where even people who don't really understand the nature of electrons or fluid dynamics or organic chemistry still accept that electrical appliances work when you turn them on, still fly in planes and ride ferryboats, and still take synthesized medicines to treat diseases or relieve pain—there are many, many people who don't think evolution is true.

No physicians must write books reiterating that, yes, bacteria and viruses are what spread infectious diseases. No physicists have to re-establish to the public that, honestly, electromagnetism is real. No psychiatrists are compelled to prove that, indeed, chemicals interacting with our brain tissues can alter our senses and emotions. No meteorologists need argue that, really, weather patterns are driven by energy from the Sun. Those things seem obvious and established now. We can move on.

But biologists continue to encounter resistance to the idea that differences in how living organisms survive and reproduce are enough to build all of life's complexity—over hundreds of millions of years, without any pre-existing plan or coordinating intelligence. But that's what happened, and we know it as well as we know anything.

If the Bible or the Qu'ran is your only book, I doubt much will change your mind on that. But many of the rest of those who don't accept evolution by natural selection, or who are simply unsure of it, may have been taught poorly about it back in school—or if not, they might have forgotten the elegant simplicity of the concept. Not to mention the huge truckloads of evidence to support evolutionary theory, which is as overwhelming (if not more so) and more immediate than the also-substantial evidence for our theories about gravity, weather forecasting, germs and disease, quantum mechanics, cognitive psychology, or macroeconomics.

Enjoying the human story

So, if these three biologists have taken on the task of explaining why we know evolution happened, and why natural selection is the best mechanism to explain it, how well do they do the job? Very well, but also differently. The titles tell you.

Shubin's Your Inner Fish is the shortest, the most personal, and the most fun. Dawkins's The Greatest Show on Earth is, well, the showiest, the biggest, and the most wide-ranging. And Coyne's Why Evolution is True is the most straightforward and cohesive argument for evolutionary biology as a whole—if you're going to read just one, it's your best choice.

However, of the three, I think I enjoyed Your Inner Fish the most. Author Neil Shubin was one of the lead researchers in the discovery and analysis of Tiktaalik, a fossil "fishapod" found on Ellesmere Island here in Canada in 2004. It is yet another demonstration of the predictive power of evolutionary theory: knowing that there were lobe-finned fossil fish about 380 million years ago, and obviously four-legged land dwelling amphibian-like vertebrates 15 million years later, Shubin and his colleagues proposed that an intermediate form or forms might exist in rocks of intermediate age.

Ellesmere Island is a long way from most places, but it has surface rocks about 375 million years old, so Shubin and his crew spent a bunch of money to travel there. And sure enough, there they found the fossil of Tiktaalik, with its wrists, neck, and lungs like a land animal, and gills and scales like a fish. (Yes, it had both lungs and gills.) Shubin uses that discovery to take a voyage through the history of vertebrate anatomy, showing how gill slits from fish evolved over tens of millions of years into the tiny bones in our inner ear that let us hear and keep us balanced.

Since we're interested in ourselves, he maintains a focus on how our bodies relate to those of our ancestors, including tracing the evolution of our teeth and sense of smell, even the whole plan of our bodies. He discusses why the way sharks were built hundreds of millions of years ago led to human males getting certain types of hernias today. And he explains why, as a fish paleontologist, he was surprisingly qualified to teach an introductory human anatomy dissection course to a bunch of medical students—because knowing about our "inner fish" tells us a lot about why our bodies are this way.

Telling a bigger tale

Richard Dawkins and Jerry Coyne tell much bigger stories. Where Shubin's book is about how we people are related to other creatures past and present, the other two seek to explain how all living things on Earth relate to each other, to describe the mechanism of how they came to the relationships they have now, and, more pointedly, to refute the claims of people who don't think those first two points are true.

Dawkins best expresses the frustration of scientists with evolution-deniers and their inevitable religious motivations, as you would expect from the world's foremost atheist. He begins The Greatest Show on Earth with a comparison. Imagine, he writes, you were a professor of history specializing in the Roman Empire, but you had to spend a good chunk of your time battling the claims of people who said ancient Rome and the Romans didn't even exist. This despite those pesky giant ruins modern Romans have had to build their roads around, and languages such as Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, French, German, and English that are obviously derived from Latin, not to mention the libraries and museums and countrysides full of further evidence.

He also explains, better than anyone I've ever read, why various ways of determining the ages of very old things work. If you've ever wondered how we know when a fossil is 65 million years old, or 500 million years old, or how carbon dating works, or how amazingly well different dating methods (tree ring information, radioactive decay products, sedimentary rock layers) agree with one another, read his chapter 4 and you'll get it.

Alas, while there's a lot of wonderful information in The Greatest Show on Earth, and many fascinating photos and diagrams, Dawkins could have used some stronger editing. The overall volume comes across as scattershot, assembled more like a good essay collection than a well-planned argument. Dawkins often takes needlessly long asides into interesting but peripheral topics, and his tone wanders.

Sometimes his writing cuts precisely, like a scalpel; other times, his breezy footnotes suggest a doddering old Oxford prof (well, that is where he's been teaching for decades!) telling tales of the old days in black school robes. I often found myself thinking, Okay, okay, now let's get on with it.

Truth to be found

On the other hand, Jerry Coyne strikes the right balance and uses the right structure. On his blog and in public appearances, Coyne is (like Dawkins) a staunch opponent of religion's influence on public policy and education, and of those who treat religion as immune to strong criticism. But that position hardly appears in Why Evolution is True at all, because Coyne wisely thinks it has no reason to. The evidence for evolution by natural selection stands on its own.

I wish Dawkins had done what Coyne does—noting what the six basic claims of current evolutionary theory are, and describing why real-world evidence overwhelmingly shows them all to be true. Here they are:

- Evolution: species of organisms change, and have changed, over time.

- Gradualism: those changes generally happen slowly, taking at least tens of thousands of years.

- Speciation: populations of organisms not only change, but split into new species from time to time.

- Common ancestry: all living things have a single common ancestor—we are all related.

- Natural selection: evolution is driven by random variations in organisms that are then filtered non-randomly by how well they reproduce.

- Non-selective mechanisms: natural selection isn't the only way organisms evolve, but it is the most important.

The rest of Coyne's book, in essence, fleshes those claims and the evidence out. That's almost it, and that's all it needs to be. He recounts too why, while Charles Darwin got all six of them essentially right back in 1859, only the first three or four were generally accepted (even by scientists) right away. It took the better part of a century for it to be obvious that he was correct about natural selection too, and even more time to establish our shared common ancestry with all plants, animals, and microorganisms.

Better than other books about evolution I've read, Why Evolution is True reveals the relentless series of tests that Darwinism has been subjected to, and survived, as new discoveries were made in astronomy, geology, physics, physiology, chemistry, and other fields of science. Coyne keeps pointing out that it didn't have to be that way. Darwin was wrong about quite a few things, but he could have been wrong about many more, and many more important ones.

If inheritance didn't turn out to be genetic, or further fossil finds showed an uncoordinated mix of forms over time (modern mammals and trilobites together, for instance), or no mechanism like plate tectonics explained fossil distributions, or various methods of dating disagreed profoundly, or there were no imperfections in organisms to betray their history—well, evolutionary biology could have hit any number of crisis points. But it didn't.

Darwin knew nothing about some of these lines of evidence, but they support his ideas anyway. We have many more new questions now too, but they rest on the fact of evolution, largely the way Darwin figured out that it works.

The questions and the truth

Facts, like life, survive the onslaughts of time. Opponents of evolution by natural selection have always pointed to gaps in our understanding, to the new questions that keep arising, as "flaws." But they are no such thing: gaps in our knowledge tell us where to look next. Conversely, saying that a god or gods, some supernatural agent, must have made life—because we don't yet know exactly how it happened naturally in every detail—is a way of giving up. It says not only that there are things we don't know, but things we can never learn.

Some of us who see the facts of evolution and natural selection, much the way Darwin first described them, prefer not to believe things, but instead to accept them because of supporting scientific evidence. But I do believe something: that the universe is coherent and comprehensible, and that trying to learn more about it is worth doing for its own sake.

In the 150 years since the Origin, people who believed that—who did not want to give up—have been the ones who helped us learn who we, and the other organisms who share our planet, really are. Thousands of researchers across the globe help us learn that, including Dawkins exploring how genes, and ideas, propagate themselves; Coyne peering at Hawaiian fruit flies through microscopes to see how they differ over generations; and Shubin trekking to the Canadian Arctic on the educated guess that a fishapod fossil might lie there.

The writing of all three authors pulses with that kind of enthusiasm—the urge to learn the truth about life on Earth, over more than 3 billion years of its history. We can admit that we will always be somewhat ignorant, and will probably never know everything. Yet we can delight in knowing there will always be more to learn. Such delight, and the fruits of the search so far, are what make these books all good to read during this important anniversary year.

Labels: anniversary, books, controversy, evolution, religion, review, science

30 September 2009

Blasphemy: funny if it weren't often so dangerous

Today is International Blasphemy Day (of course there are a Facebook page and group). The event is held on the anniversary of the 2005 publication in Denmark of those infamous cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad. Subversive cartoonist Robert Crumb is coincidentally in on the action this year too, with his illustrated version of the Book of Genesis.

Today is International Blasphemy Day (of course there are a Facebook page and group). The event is held on the anniversary of the 2005 publication in Denmark of those infamous cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad. Subversive cartoonist Robert Crumb is coincidentally in on the action this year too, with his illustrated version of the Book of Genesis.

Blasphemy Day isn't aimed merely at Islam or Christianity, but at all and any religions and sects that include the concepts of blasphemy, apostasy, desecration, sacrilege, and the like. "Ideas don't need rights," goes the tagline, "people do."

While my grandfather was a church musician, and my parents had me baptized and took me to services for a short while as a youngster, I've never been religious, so no doubt I blaspheme regularly without even thinking about it. I've written plenty about religion on this blog in the past few years, often blasphemously in someone's opinion, I'm sure. In 2007 I wrote my preferred summary of my attitude:

The beauty of a globular cluster or a diatom, the jagged height of a mountain or the depth of geological time—to me, these are natural miracles, not supernatural ones.

In that same post, I also wrote tangentially about blasphemy:

...given the scope of this universe, and any others that might exist, why would any god or gods be so insecure as to require regulated tributes from us in order to be satisifed with their accomplishments?

If the consequences—imposed by humans against each other, by the way—weren't so serious in so many places, the idea of blasphemy would be very funny. Even if there were a creator (or creators) of the Universe, how could anything so insignificant as a person, or even the whole population of a miniscule planet, possibly insult it?

We're talking about the frickin' Universe here. (Sorry, should be properly blasphemous: the goddamned Universe.) You know, 13.7 billion years old? Billions of galaxies, with billions of stars each? That one? Anything happening here on Earth is, on that scale, entirely irrelevant.

To my mind, there are no deities anyway. But if you believe there are, please consider this: it's silly to think that a god or gods could be emotionally fragile enough to be affected by our thoughts and behaviours, and even sillier to believe that people could or should have any role in enforcing godly rules. Silliest yet is that believers in a particular set of godly rules should enforce those rules on people who don't share the same belief.

Being a good person is worth doing for its own sake, and for the sake of our fellow creatures. Sometimes being good, or even simply being accurate, may require being blasphemous by someone else's standards. Today is a day to remember that.

Labels: controversy, linkbait, politics, religion, science

28 June 2009

Links of interest 2006-06-21 to 2006-06-27

While I'm on my blog break, more edited versions of my Twitter posts from the past week, newest first:

- My wonderful wife got me a Nikon D90 camera for my 40th birthday this week. I'm thinking of selling my old Nikon D50, still a great camera. Anyone interested? I was thinking around $325. I also have a brand new 18–55 mm lens for sale with it, $150 by itself or $425 together. I have all original boxes, accessories, manuals, software, etc., and I'll throw in a memory card, plus a UV filter for the lens.

- Roger Hawkins's drum track for "When a Man Loves a Woman" (Percy Sledge 1966): tastiest ever? Hardly a fill, no toms, absolutely delicious.

- Thank you thank you thank you to everyone who came to my 40th birthday party—both for your presence and for the presents. Photos from the event, held June 27, three days early for my actual birthday on Tuesday, are now posted (please use tag "penmachinebirthday" if you post some yourself).

- I think Twitter just jumped the shark. In trending topics, Michael Jackson passed Iran, OK, but both passed by Princess Protection Program (new Disney Channel movie)?

- AT&T (and Rogers, presumably) is trying to charge MythBusters' Adam Savage $11,000 USD for some wireless web surfing here in Canada.

- After more than 12 years buying stuf on eBay, here's our first ever item for sale there. Nothing too exciting, but there you go.

- Michael Jackson's death this week made me think of comparisons with Elvis, John Lennon, and Kurt Cobain. Lennon and Cobain still seemed to have some artistic vitality ahead of them. Feel a need for Michael Jackson coverage? Jian Ghomeshi (MP3 file) on CBC in Canada is the only commentator who isn't blathering mindlessly. But as a cancer patient myself, having Farrah Fawcett and Dr. Jerri Nielsen (of South Pole fame) die of it the same day is a bit hard to take.

- Seattle's KCTS 9 (PBS affiliate) showed "The Music Instinct" with Daniel Levitin and Bobby McFerrin. If you like music or are a musician, it's worth watching, even if it's a bit scattershot, packing too much into two hours.

- New rule: when a Republican attacks gay marriage, lets assume he's cheating on his wife (via Jak King).

- The blogs and podcasts I'm affiliated with are now sold on Amazon for its Kindle e-reader device, for $2 USD a month. I know, that's weird, because they're normally free, and are even accessible for free using the Kindle's built-in web browser, so I don't know why people would pay for them—but if you want to, here you go: Penmachine, Inside Home Recording, and Lip Gloss and Laptops. Okay, we're waiting for the money to roll in...

- Great speech by David Schlesinger from Reuters to the International Olympic Committee on not restricting new media at the Olympics (via Jeff Jarvis).

- TV ad: "Restaurant-inspired meals for cats." Um, have they seen what cats bring in from the outdoors?

- I planned to record my last segment for Inside Home Recording #72, but neighbour was power washing right outside the window (in the rain!). Argh.

- You can't trust your eyes: the blue and green are actually the SAME COLOUR.

- Can you use the new SD card slot in current MacBook laptops for Time Machine backups? (You can definitely use it to boot the computer.) Maybe, but not really. SDHC cards max out at 32GB (around $100 USD); the upcoming SDXC will handle more, but none exist in Macs or in the real world yet. Unless you put very little on the MacBook's internal drive, or use System Preferences to exclude all but the most essential stuff from backups, then no, SD cards are not viable for Time Machine.

- Some stats from Sebastian Albrecht's insane thirteen-times-up-the-Grouse Grind climb in one day this week. He burned 14,000+ calories.

- Even though I use RSS extensively, I find myself manually visiting the same 5 blogs (Daring Fireball, Kottke, Darren Barefoot, PZ Myers, and J-Walk) every morning, with most interesting news covered.

- I never get tired of NASA's rocket-cam launch videos.

- Pat Buchanan hosts conference advocating English-only initiatives in the USA. But the sign over the stage is misspelled.

- Who knew the Rolling Stones made an (awesome) jingle for Rice Krispies in the mid-1960s?

- Always scary stuff behind a sentence like, "'He is an expert in every field,' said a church spokeswoman."

- Kodachrome slide film is dead, but Fujichrome Velvia killed it a long time ago. This is just the official last rites.

- My friends Dave K. and Dr. Debbie B. did the Vancouver-to-Seattle bicycle Ride to Conquer Cancer (more than 270 km in two days) last weekend. Congrats and good job!

- My daughter (11) asks on her blog: "if Dad is so internet famous, I mean, Penmachine is popular, then, maybe I am too..."

- Evolution of a photographer (via Scott Bourne).

Labels: amazon, apple, backup, birthday, cancer, film, geekery, linksofinterest, music, news, olympics, photography, politics, religion, science, space, television, twitter

02 June 2009

Those damned angry atheists

Christopher Hitchens was his usual bombastic and arrogant self on CBC's "Q" today (MP3 file). That's no surprise, since he is perhaps the angriest—or at least the most provocative—of the angry New Atheists who have had bestselling books over the past few years. Many religious people, and a good number of my fellow atheists too, think Hitchens's take-no-prisoners approach is wrong and counterproductive. Why, they ask, should atheists antagonize believers the way he and others, like Richard Dawkins, do?

"Q" host Jian Ghomeshi asked Hitchens a similar question today:

Tell me who you think your audience is, because you're quite aggressive with your argument. [...] If you really want to change things, it might take some effort to overcome organized religion in the world, but I'm wondering if [...] being a little softer in your approach might be more effective?

It's true that most atheists would prefer to be more conciliatory towards the world's religious majorities. But I think Hitchens and his compatriots serve a valuable purpose. With their polemics, their public profiles, indeed with their anger, they have made atheism visible in this new century, especially in America. Without them, we might not have heard Barack Obama's acknowledgment of non-believers in his inaugural address.

The angry New Atheists are like the activist vanguard of the LGBT rights movement, and of other civil rights movements before it. Not every gay person wants to march in protests, or make films outing hypocritical homosexual politicians. But the demands and self-righteousness of the vanguard are why same-sex marriage is a reality in Canada, and in several European countries and American states, today, rather than decades from now.

I grew up in an ostensibly secular Canada in the '70s, but we still said a prayer every morning in public school, and the Lord's Day Act prevented stores from opening on Sunday. Those rituals didn't offend me at the time, but as a non-religious youngster, I still felt like an outsider. The assumption seemed to be not only that everyone was religious, but that we were all Christians too. That has changed, largely because of Canada's increasing multiculturality.

High-profile writers like Hitchens and Salman Rushdie and Douglas Adams and Barbara Ehrenreich; scientists like Richard Dawkins and David Suzuki and Richard Feynman; comedians like Julia Sweeney and Ricky Gervais and George Carlin; musicians like Ani DiFranco and Mick Jagger and Eddie Vedder; actors like Omar Sharif and Eva Green and Emma Thompson and Ian McKellen and Katharine Hepburn; and others from Penn and Teller to Linus Torvalds to the MythBusters to Nigella Lawson—around the world, all profess their atheism.

In doing so, they affirm that the non-religious and non-spiritual among us are part of the full and honourable diversity of human society. So the audience for Christopher Hitchens need not be religious people he is trying to de-convert (even if that is his goal). Rather, it can be the millions of us who believe in no gods or spirits, and who are comfortable saying so, because Hitchens is shouting it too.

UPDATE: Biologist Jerry Coyne, who is outspoken in his assertion that science and religion are incompatible, has an interesting post on this same topic.

Labels: cbc, controversy, radio, religion, writing

05 February 2009

The big gap

For the past couple of weeks I've been reading God's Crucible

For the past couple of weeks I've been reading God's Crucible, a history book by David Levering Lewis—which I gave to my dad for Christmas, but which he's loaned back to me. Today I got a lot of reading done, because my body was screwing with me: I'll have to skip my cancer medications for the next day or two because the intestinal side effects, unusually, lasted all day today and into the night, and I have to give my digestive system (and my butt) a rest.

Lewis's book covers, at its core, a 650-year span from the 500s to the 1200s, during which Islam began, and rapidly spread the influence of its caliphate from Arabia across a big swath of Eurasia and northern Africa, while what had been the Roman Empire simultaneously fragmented into its Middle Ages in Europe. That's a time I've known little about until now.

The history I took in school and at university covered lots of things, from ancient Egypt and Babylon up to the Roman Empire, and from the Renaissance to the 20th century, as well as medieval England. I learned something about the history of China and India, as well as about the pre-Columbian Americas. But pre-Renaissance Europe and the simultaneous rapid expansion of the dar al-Islam are a particularly big gap for me.

Whose Dark Ages?

I knew a little about Moorish Spain, and a tad about Charlemagne and Constantinople, but otherwise it was just the Dark Ages for me, and for a lot of students who learned the typical Eurocentric view of history. There was much more going on in more populated and interesting parts of the world, though. While Europeans (not even yet named that) eked along with essentially no currency, trade, or much cultural exchange beyond warfare with horses, swords, and arrows:

- China went through the Sui, Tang, and Song dynasties, reaching the peak of classical Chinese art, culture, and technology.

- India also saw several dynasties and empires, as well as its own Muslim sultans.

- Large kingdoms of the Sahel in near-equatorial Africa arose, including those of Ghana, Takrur, Malinke, and Songhai.

- The Maya in Central America developed city-states and the only detailed written language in the Western Hemisphere.

- The seafaring Polynesians reached their most distant Pacific outposts, including Easter Island, Hawaii, and New Zealand.

Crucially important, of course, was Islam. Muhammad was born in the year 570, and shortly after he died about six decades later, Muslim armies exploded out of Arabia and conquered much of the Middle East and North Africa, then expanded east and north into Central Asia. By the early 700s, the influence of the caliphate headquartered in Damascus had reached Spain (al-Andalus), where Muslims would remain in power for 700 years.

In his book, Lewis flies through the origins of Islam, the foundations of the Byzantine and Roman branches of the Catholic Church after the fall of Rome, the interminable conflict between it and Zoroastrian Persia to the east, the Muslim caliphate's sudden rise up the middle to take over the eastern and southern Mediterranean, and the crossing of Islamic armies into Europe at Jebel Tariq (now called Gibraltar) in 711. Then things bog down a little.

I'm about half-way through the book, and Lewis throws out so many names, alternate names for the same people, events, places, and such that it's hard to keep up. He hops back and forth in time enough that what story he's trying to tell isn't always clear—he was won the Pulitzer Prize, but that was for more focused historical biographies, such as of W.E.B. Du Bois, rather than sweeping surveys like this one. His writing isn't overly complex, and I'm learning a lot, but it's a tough go sometimes. Still, I think it will be worth sticking it out.

Labels: books, europe, history, religion, review

28 January 2009

Saddleback

The world's favourite sex columnist and podcaster, Dan Savage, has discovered another good definition of the word saddleback, with reference to Pastor Rick Warren's Saddleback Church.

The back story: Rick Warren has gajillions of followers across the U.S., and is the author of the bestseller The Purpose Driven Life. He gave the benediction prayer at President Obama's inauguration, much to the chagrin of gay activists and other people who supported Obama's social agenda—because Warren supported California's Prop 8 to abolish gay marriage, and follows the usual conservative evangelical line on most other social and sexual issues too. Even so, he is considered progressive by some people (or not conservative enough by some others) because he emphasizes improving the lives of poor people around the globe, as well as combating global climate change.

Warren's church is called the Saddleback Church, so Dan Savage asked his readers and listeners for another good definition of the word. Hence saddlebacking.

Labels: americas, controversy, politics, religion, sex

21 January 2009

Obama, religion, and hard work ahead

I was driving to my oncologist appointment just after 9:00 a.m. yesterday when the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court inaugurated Barack Obama as President of the United States. I heard it on the radio, and I teared up a little. The oath of office itself was surprisingly short, and both Obama and the Justice stumbled a little with the words in their enthusiasm—it sounded refreshingly informal and real.

Almost a year ago, even before the economy started seriously tanking, I wrote about Obama, saying:

America and the rest of us need inspiration now. America's citizens need to say to us, and to themselves, "We have been on the wrong path, and we will choose a different and better way." To see and to listen to Barack Obama as president will demonstrate the beginning of that choice. If I'm right, I think he will win.

He did win. Yesterday he could celebrate and dance; today he has to start doing stuff. Web nerds like me see good signs in small things, like the new whitehouse.gov website, which is well designed, has a blog with RSS, uses valid code, and is search engine friendly. More importantly, he has already ordered a halt to military commission prosecutions at Guantánamo Bay. He meets his military advisors this afternoon to plan withdrawal of U.S. armed forces from Iraq.

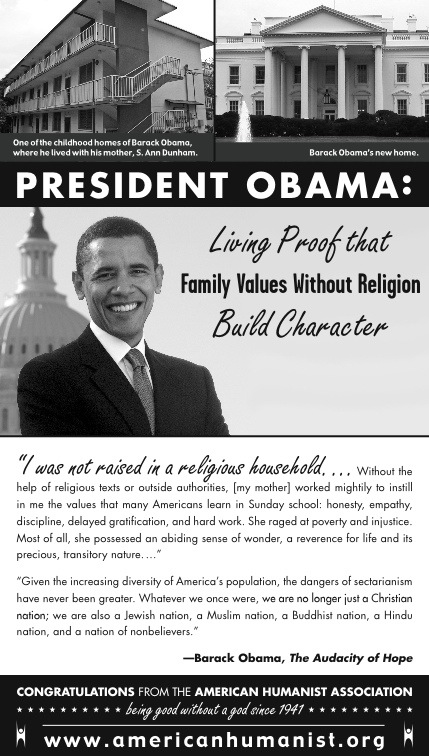

His response to America's unusual religiosity (for a Western democracy) is also worth noting. President Obama was not involved with and did not endorse this ad in the Washington Post from the American Humanist Association (via PZ Myers), but I think it is a good sign:

The headline is "President Obama: Living proof that family values without religion build character," with supporting quotes from his bestseller The Audacity of Hope ("I was not raised in a religious household..."). Some people are gonna get steamed over this one, I'm sure, and use it to continue maligning the new President. But though he is a Christian now, Obama obviously knows the benefits of a secular state, and why his country's founders created America as such. He understands that the non-religious —like both his parents—can be good people and raise healthy children, like him, who make wise choices.

That he and his administration not only recognize, but celebrate the diversity of their country—and that, in his own carefully crafted words during the inaugural address, "our patchwork heritage is a strength, not a weakness"—is a strength in itself. He, like us, has seen in the past decade how parochial sectarianism can do vast harm around the world.

The man has enough good will from Americans, and many of the other few billion of us, that he need not work miracles immediately, but he also seems to know that he doesn't have too much time. He must work with the citizens who elected him to realign his country's domestic, foreign, energy, and environmental policies. He must translate his ability to inspire as a candidate into a mandate to inspire as the world's most powerful person. I think, and hope, that he is up to the task.

Labels: americas, government, politics, racism, religion

03 November 2008

Links of interest (2008-11-03):

- “[Obama] said he likes to go out trick-or-treating, but he can’t anymore. [...] He said he guessed he could have worn a Barack Obama mask.”

- America contains a strange dichotomy about teenage sex: "Social liberals in the country's 'blue states' tend to support sex education and are not particularly troubled by the idea that many teen-agers have sex before marriage, but would regard a teen-age daughter's pregnancy as devastating news. And the social conservatives in 'red states' generally advocate abstinence-only education and denounce sex before marriage, but are relatively unruffled if a teen-ager becomes pregnant, as long as she doesn't choose to have an abortion."

- From the same post at The Slog, back in 1970 Aretha Franklin sang and played piano in a lesson in soul that today's diva singers could still learn a thing or two (or twenty) from. In particular, her melisma (one syllable, many notes) is hardly noticeable, because she uses it sparingly and for (perhaps instinctive) emotional emphasis, rather than as a special effect. Maya Rudolph nailed it in this SNL satire in 2006 (sorry for the lousy audio, but you'll get it).

- Darren, who never adds salt or pepper to a prepared meal, wonders why so many of us do, even before we taste it. Shouldn't food, he asks, be properly seasoned before it arrives?

- Lisa has some good tips for photography on rainy days (also at TWIP)—especially useful right now in Vancouver.

- It's inevitable that an article (via Pharyngula) about an estranged son of the despicable Fred Phelps and his Westboro Baptist Church provokes a nasty flame war in the comments, but to have Phelps's equally vitriolic daughter Shirley (who obviously keeps up regular ego-surfing) be the first to comment brings it to a new level. Nice work by The Ubyssey, by the way—their journalism and copy editing seem to have improved since my days at UBC a couple of decades ago.

Labels: education, food, linksofinterest, music, photography, politics, religion, sex, weather

21 June 2008

Quandary: should I see "Expelled" or not?

Back in March I wrote about the dumb behaviour of the people who made the film Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed. Now, probably because of that posting and my other entries here about science, I've been invited by distributor KinoSmith to attend a press screening of the movie here in Vancouver next week. I'm wondering if I should bother to go.

Back in March I wrote about the dumb behaviour of the people who made the film Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed. Now, probably because of that posting and my other entries here about science, I've been invited by distributor KinoSmith to attend a press screening of the movie here in Vancouver next week. I'm wondering if I should bother to go.

Propagandumentary

First, some background about Expelled. It is a purported documentary, supposedly a Michael Moore–style critique of the current academic establishment of evolutionary biology. I enjoy a good intellectual debate, especially about topics as important to us as the development of life on earth, so if that's what Expelled really were, it might make an interesting film.

However, the evidence indicates that instead it is, in the words of New York Times reviewer Jeannette Catsoulis , "one of the sleaziest documentaries to arrive in a very long time [and] a conspiracy-theory rant masquerading as investigative inquiry." (That is the first line of her review.) Here, for instance, is a quote about Expelled from narrator Ben Stein:

Love of God and compassion and empathy leads you to a very glorious place. Science leads you to killing people.

It's fine for people to disagree, but a blanket line like "science leads you to killing people" is not only wrong, it's profoundly simplistic and inflammatory. Would religious people be likely to attend a movie promoted by lines like, "religion leads you to killing people"? I suspect, for instance, that many have been put off reading Christopher Hitchens's book God Is Not Great, with its chapter, "Religion Kills." (I haven't read it either, but not for that reason.)

Is it worth my time?

Okay, fine, so I'm not disposed to like the movie, but am I being closed-minded about it? Here's another issue. Totally beyond its mistaken premises, its misleading of interviewees, its senseless invocation of Hitler and Stalin as inevitable consequences of accepting natural selection, its plagiarism, and its promotion of intelligent design as a supposedly scientific idea instead of as a front for (mostly biblical) creationism, Expelled is also, by all indications, a lousy movie: poorly made, badly edited, patronizing, disorganized, and often dull.

Anyway, here's my quandary. I'm interested in finding out what all the fuss is about, so part of me thinks I should use the free double passes that arrived in the mail yesterday, and take three friends to see Expelled next Thursday. I wouldn't pay to see it, because I don't think the filmmakers deserve my money, but these are free tickets, and it's actually costing them for me to go.

On the other hand, I still remember seeing Highlander 2 back in 1991. That movie was so bad that it somehow made its predecessor worse: in my mind, it tainted the first Highlander film, which I had enjoyed. I get the feeling that Expelled is similarly bad, the kind of film that makes you wish you'd never seen it and had those few hours of your life back.

Probably not

We have a friend visiting from Australia for a couple of weeks, and our family would like to spend time with her. My daughters' final piano lesson is that same day. I suspect I have many better things to do, such as hanging out in my back yard, or maybe having a nap.

So, after my fine promotion here, does anyone want four free tickets to see Expelled next Thursday, June 26, 2008, at 7:00 p.m., at Tinseltown in downtown Vancouver? The tickets say, "Arrive early as theatre capacity is limited and seating is not guaranteed," by the way. Let me know if you want them, even if just for the hell of it. (Pun intended.)

Labels: biology, controversy, creationism, intelligentdesign, linkbait, movie, naturalselection, religion, science

21 March 2008

Some people have bad ideas

I like to give people the benefit of the doubt, but sometimes they squander it. A couple of examples.

A few months ago, I gave a bit of a mixed review to Why Beautiful People Have More Daughters, a book about evolutionary psychology. It turns out that the main author, Satoshi Kanazawa, has taken his ideas to at least one ridiculous and terrifying extreme:

Imagine that, on September 11, 2001, when the Twin Towers came down, the President of the United States was not George W. Bush, but Ann Coulter. What would have happened then? On September 12, President Coulter would have ordered the US military forces to drop 35 nuclear bombs throughout the Middle East, killing all of our actual and potential enemy combatants, and their wives and children. On September 13, the war would have been over and won, without a single American life lost.

Yes, we need a woman in the White House, but not the one who’s running.

Uh, okay.

That's straight-on crazy talk (not to mention almost certainly incorrect in its results). Doesn't raise my opinion of his book, that's for sure.

On the other side of the evolutionary aisle are the producers of Expelled, a documentary claiming that the academic and scientific establishment are unfairly quashing free speech, by shunning researchers who promote intelligent design/creationism and other "critiques" of evolutionary biology. The movie is hosted by Ben Stein (probably best known as the teacher who said, "Bueller? Bueller?"), and also apparently argues that accepting evolution leads inevitably to atheism, which then (get this) led to the Stalinist pogroms and the Holocaust.

Uh, okay.

Among those interviewed in the film is PZ Myers, an American biology professor. He is also almost as well-known an atheist and staunch critic of religion and creationism as Richard Dawkins. He says that the producers were dishonest when asking him to appear in Expelled, claiming that its working title was Crossroads (although the expelledthemovie.com domain had apparently already been registered) and that it was a more objective examination of science and religion, rather than a project advocating for creationism. He has been scathingly critical of the film ever since.

Myers's interview ended up in the film anyway, which has been pre-screened a few times in the U.S. for largely hand-picked evangelical Christian audiences. One of those screenings just occurred in Minnesota, where Myers happened to be, so he signed up on the website for tickets for him, his family, and some friends. But when he showed up, the film's producer, who was also present and helped to organize the screening, barred him from entering.

His family and friends got in. One of those friends, also someone interviewed for the film under false pretenses?

Richard Dawkins. Yes, that one. No, really.

It's not turning into a good PR move for the movie's producers.

Labels: biology, controversy, creationism, intelligentdesign, movie, naturalselection, religion, science

20 March 2008

A billion years, or 600 million, give or take

How does evolution explain something like DNA and how it's decoded? Natural selection/chance-change over billions of years doesnt seem adequate to explain it. Are there other evolutionary mechanisms that might explain it?

Also, DNA seems very clearly to be instructions/information. From an evolutionary standpoint, would that be an illusion because [we humans interpret] what turns out to be chance results as something more meaningful and organized because the result kind of works?

Now, beware, since IANAEBOP (I Am Not An Evolutionary Biologist Or Philosopher). I do have pretty decent background in biology generally, it being my degree and all, and that means I need to understand natural selection well. So here goes my take.

What's chance, what isn't?

One of the issues here is that too often people talk about natural selection, including the initial appearance of DNA, as a random process. It's actually much the opposite: yes, mutations (i.e. the source material or "seeds" for evolutionary change) occur randomly, but the ones that persist because they lead to greater reproductive success are completely non-random. Non-random rules arising from natural processes filter out almost all the random stuff, leading to evolutionary processes that build upon themselves to generate new things.

But non-randomness doesn't have to imply conscious agency (at least I don't think so). Nor does it imply inevitability, or even directionality, really. If you rolled back the clock and started things over again with the first simple microorganisms, or at any later stage, even with essentially the same conditions, the result might very well have turned out very differently.

Evolution is a historical process, and like human history, there are so many inter-related, contingent influences going on that if we, say, started over again 75 million years ago with dinosaurs, even if an asteroid still wiped them out, there's no guarantee a human-like intelligence would arise later. Or if it did, that primates would necessarily be what did it.

Similarly, roll back farther, and would insects end up as the dominant multicellular animals again? Might woody flowering plants once more come to dominate over ferns and other now less common forms? Maybe not.

You can think of an analogy in something like the pattern of a streambed. Yes, the movement of individual water molecules or sand grains may be essentially random, but gravity and friction and a variety of other simple laws of nature, interacting in a very complex way, make it so that the result—the tree-like form of a drainage basin—has a very non-random structure. (If you drop something on earth, it falls down. If things were random, you'd have no way to predict which direction it would go.)

But, yet again, if you rolled back the clock and started the erosion process all over again, the stream's course might run in a very different direction. There would still be a tree-like structure constrained by natural laws, but the details of it would be totally different, so you couldn't plan to build a house or waterwheel or hydro dam in a particular location in advance.

The vastness of time

Another issue is time. Our brains really aren't well equipped to handle the kinds of time scales this stuff happens on. Something like DNA seems irredeemably complicated to have arisen by the hit-and-miss processes we're talking about. It's too well built. (Of course, the process also has its flaws, which is why people like me get cancer.) But we're used to watching stuff happen over the course of minutes or hours or days or weeks or months or years or maybe decades. The rise and fall of civilizations may take centuries. To us that seems like a long time.

Evidence seems to indicate that DNA first appeared pretty early on in earth's history. But it still took something like 600 million years, or maybe closer to a billion. Even if it were completely random (rather than a rule-driven process with random "seeds"), a lot of amazing things could happen totally by chance in 600 million years. And a lot of amazing things have happened in the 4 billion years since, some random, some not.

Humans have never witnessed a large asteroid impact on earth. As far as our actual experience (even on an evolutionary time scale) is concerned, it has never happened. But given enough time, tens or hundreds of millions of years, it pretty much must happen again, and it has happened several times before. So we can consider things impossible when, in the long run, they are inevitable, or at least probable.

Would DNA, or something like it, inevitably have arisen on earth, given enough time? We don't know, and can't know yet. That's why looking for unrelated life elsewhere is important: even if it's non-intelligent life, finding something that arose separately from life on earth would tell us that life-driving processes are at least reasonably likely in this universe.

Or maybe it really is nearly (but not quite) impossible, and it only happened here, once in all these billions of years there have been stars and planets. I hope not, but it could be.

Saving a step

Now, if you step back and ask why natural laws are structured in such a way that contingent, historical evolution can happen even once (or even why atoms and molecules can form at all in the first place, rather than just creating a universe that's nothing but a soup of plasma), that enters into realms of philosophy that I don't think we may ever be able to answer.

Many will answer that God must have made those rules. But if I think like that, I always have to ask: then what made the God (or gods) that could make those rules, and by what meta-rules? In my mind, it's the same problem, just one step further, so it isn't really an answer at all.

I'm comfortable enough thinking that life and the DNA that lets it propagate "just happened" (perhaps the greatest oversimplification it would ever be possible to make in any circumstance). And with observation and intelligence, we're able to understand very much about how things have happened since, without having to resort to supernatural explanations that, by definition, we cannot analyze because their rules must be inscrutable to us.

Labels: biology, evolution, history, intelligentdesign, naturalselection, religion, science, time

09 March 2008

What does a film about gays and religion mean to me?

At the video store yesterday my wife suggested we pick up For the Bible Tells Me So, a documentary about Christian families whose children come out as gay. Despite a slightly silly and jarring animated interlude, it's a good film.

It would be especially worthwhile for people in similar situations: those parents, relatives, and friends who have been brought up to think of gays and lesbians as "abominations" (in the words of an oft-cited Bible passage) but who want to maintain their religion and also accept a loved one's homosexuality. Or for those raised conservatively Christian who are gay themselves, and struggle with it.

But I'm neither gay nor religious. I'm an atheist, and my many friends who are gay, lesbian, or transgendered don't offend my sensibilities in any way. For me, the movie is more of an anthropological study, and a fascinating one because a religious life is so far from my own experience.

It makes sense to me that those who work to reconcile the Bible (or the Qu'ran, or other religious books) with many aspects of modern life often have tough work to do. Those books were written centuries or millennia ago, by people who knew nothing of gravitational theory, fossils, deep time, microbiology and germs, Big Bang cosmology, evolution, quantum mechanics and relativity, plate tectonics, organic and inorganic chemistry, absolute zero, the concept of a vacuum, and DNA—or even of the existence of the Americas, Australia, Antarctica, and the Pacific Ocean.

So if authorities at the time thought that homosexuality was unclean or improper or abominable, of course they wrote that into their religious texts. Accordingly, that same passage of the Bible also condemns wearing clothes of mixed fibres, cutting your hair a certain way, and eating shellfish and pork as equally wrong. Plus, other passages of those same books condone or accept slavery, physical abuse of women, pillaging and murder during wartime, and other things many of us now consider abominable.

And indeed, still other parts say you should sell all you have and give the proceeds to the poor, not squander your wealth wastefully, go forth and multiply, not be arrogant and boastful, forgive debts, and love your neighbour. Oh, and you shall not work on the Sabbath, shall honour your parents, shall not kill or commit adultery or bear false witness, etc.

You can consider those proclamations the words of men now long dead—words sometimes wise and transcendent, sometimes narrow-minded and obsolete. Or you can consider them the word of God. Then you might have to interpret what those words could mean in a time where we have stood on the Moon, created antibiotics, invented the Internet, changed the climate, developed sexual reassignment surgery, measured the age of the Universe, and reached a population exceeding six billion.

I find those interpretations interesting. But unlike the subjects of the film, including well-known gay Episcopal Bishop Gene Robinson, for me they are unnecessary. I have no personal need to reconcile modern ethics and morals with the Bible or the Qu'ran or the Vedas; with the teachings of Buddha or Lao Tzu or Confucius; or for that matter with the myths of the Spartans, Aztecs, Bantu, Haida, or Maori. Any or all of those things can inform my sense of right and wrong, but they don't define it.

All of us struggle to be good people. For the Bible Tells Me So can help some of us in that struggle. It's worth watching, whether its struggle is yours or not.

Labels: americas, film, movie, religion, science, sex

10 January 2008

Praise cheesus

25 October 2007

How to read the Bible

There's been a bit of a buzz recently about the book The Year of Living Biblically, where author A.J. Jacobs, an agnostic Jew, chose to live by all the rules in the Bible (even the obscure ones, and mostly from the Old Testament) as much as he could, for an entire year. The Bible is of course a fascinating book, even for atheists like me, for whom it is not a divine revelation but a magnificent human construction.

Like the Quran, the Hindu Vedas, Buddhist Sutras, the Analects of Kong Fuzi (Confucius), and the myths and stories of everyone from the Egyptians, the Greeks and Romans, and the Norse to the Inca, the Haida, and the vast diaspora of Polynesia, the Bible has profoundly affected, and been the foundation of, huge parts of human culture and history. I know less about it (and those other works) than I should.

I'm not sure Jacobs's book would be my best resource, though I'm sure it's funny and revealing—in a radio interview with Jacobs I heard this morning, I discovered that wearing clothes whose fibres mix wool and linen is apparently forbidden. Daily showers are, however, apparently fine, even though I've heard of some religious Christians and Jews who disdain "bathing for pleasure." And in the Bible (New Testament especially), there appears to be a whole lot more about helping the poor and needy than the behaviour of a lot of people who claim to be literalist Christians would indicate.

Perhaps a better introduction would be How to Read the Bible, by Richard Holloway, the controversial retired Anglican Bishop of Edinburgh. On the most recent CBC "Ideas" podcast, he and Paul Kennedy engage in a fascinating discussion (MP3, available on CD once that MP3 link expires) of his book.

Richard Dawkins, most prominent atheist, was raised Anglican, and he has called Anglicanism a watered-down, weakened strain of the virus he thinks religion is. Holloway surely does not disabuse Dawkins of that assessment, especially when he writes things like:

One of the constant themes of the Bible is the human capacity to get God wrong, which is why the distance between those who believe God is a human invention and those who believe God is real is narrower than we might think.

and:

The afterlife of great texts [like the Bible] eclipses the intention of the original author, even if we think we know what it was.

and:

Retrojecting ideas from a later perspective into the text of the Hebrew Bible became a major enterprise in Christianity, with two branches, historical and theological.

Those are just from the first chapter. I knew nothing about Holloway until I heard the podcast, but I suspect that a lot of believing people—especially those prone to Biblical literalism—no longer consider him a good Anglican, or a good Christian, regardless of his previous senior role in the church.

Now, by nature, I know pretty much nothing about the past 2000 years of Christian theology, just as I am largely ignorant of what intellectuals among Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, Jews, Zoroastrians, Jains, Buddhists, and others have thought and written about their own faiths—or what modern academics outside those religions have to say about them. I'm not particularly interested in becoming a religious expert either, for even all religions put together are only a part of how humans try to understand and organize the world (not the part that most interests me).

But from what I have heard and read this week, I like Holloway's approach, and will probably read his book at some point, which I guess means I'll need to get to reading that Bible eventually too. From previous comments on this blog (and surely some more to come on this post), a small number of you readers might think doing so will lead to a born-again conversion in me, especially with my cancer and everything now, or that I've already consigned myself to Hell unless I repent pretty darn soon.

If I were you, I wouldn't bet any money on that.

Labels: bible, books, cbc, controversy, podcast, religion, science

06 October 2007

Religion and fundamentalism

This is an excellent written debate between American pundits Andrew Sullivan (iconoclastic gay right-winger and moderate Christian) and Sam Harris (well-known atheism activist and proponent of meditation) on the nature of religion and fundamentalism. It happened last spring, but I only just stumbled on it.

They continue to disagree at the end, but manage to spar more politely and interestingly than the usual shouting matches on the subject.

Labels: andrewsullivan, creationism, debate, evolution, religion, samharris