Penmachine

21 June 2008

Quandary: should I see "Expelled" or not?

Back in March I wrote about the dumb behaviour of the people who made the film Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed. Now, probably because of that posting and my other entries here about science, I've been invited by distributor KinoSmith to attend a press screening of the movie here in Vancouver next week. I'm wondering if I should bother to go.

Back in March I wrote about the dumb behaviour of the people who made the film Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed. Now, probably because of that posting and my other entries here about science, I've been invited by distributor KinoSmith to attend a press screening of the movie here in Vancouver next week. I'm wondering if I should bother to go.

Propagandumentary

First, some background about Expelled. It is a purported documentary, supposedly a Michael Moore–style critique of the current academic establishment of evolutionary biology. I enjoy a good intellectual debate, especially about topics as important to us as the development of life on earth, so if that's what Expelled really were, it might make an interesting film.

However, the evidence indicates that instead it is, in the words of New York Times reviewer Jeannette Catsoulis , "one of the sleaziest documentaries to arrive in a very long time [and] a conspiracy-theory rant masquerading as investigative inquiry." (That is the first line of her review.) Here, for instance, is a quote about Expelled from narrator Ben Stein:

Love of God and compassion and empathy leads you to a very glorious place. Science leads you to killing people.

It's fine for people to disagree, but a blanket line like "science leads you to killing people" is not only wrong, it's profoundly simplistic and inflammatory. Would religious people be likely to attend a movie promoted by lines like, "religion leads you to killing people"? I suspect, for instance, that many have been put off reading Christopher Hitchens's book God Is Not Great, with its chapter, "Religion Kills." (I haven't read it either, but not for that reason.)

Is it worth my time?

Okay, fine, so I'm not disposed to like the movie, but am I being closed-minded about it? Here's another issue. Totally beyond its mistaken premises, its misleading of interviewees, its senseless invocation of Hitler and Stalin as inevitable consequences of accepting natural selection, its plagiarism, and its promotion of intelligent design as a supposedly scientific idea instead of as a front for (mostly biblical) creationism, Expelled is also, by all indications, a lousy movie: poorly made, badly edited, patronizing, disorganized, and often dull.

Anyway, here's my quandary. I'm interested in finding out what all the fuss is about, so part of me thinks I should use the free double passes that arrived in the mail yesterday, and take three friends to see Expelled next Thursday. I wouldn't pay to see it, because I don't think the filmmakers deserve my money, but these are free tickets, and it's actually costing them for me to go.

On the other hand, I still remember seeing Highlander 2 back in 1991. That movie was so bad that it somehow made its predecessor worse: in my mind, it tainted the first Highlander film, which I had enjoyed. I get the feeling that Expelled is similarly bad, the kind of film that makes you wish you'd never seen it and had those few hours of your life back.

Probably not

We have a friend visiting from Australia for a couple of weeks, and our family would like to spend time with her. My daughters' final piano lesson is that same day. I suspect I have many better things to do, such as hanging out in my back yard, or maybe having a nap.

So, after my fine promotion here, does anyone want four free tickets to see Expelled next Thursday, June 26, 2008, at 7:00 p.m., at Tinseltown in downtown Vancouver? The tickets say, "Arrive early as theatre capacity is limited and seating is not guaranteed," by the way. Let me know if you want them, even if just for the hell of it. (Pun intended.)

Labels: biology, controversy, creationism, intelligentdesign, linkbait, movie, naturalselection, religion, science

21 March 2008

Some people have bad ideas

I like to give people the benefit of the doubt, but sometimes they squander it. A couple of examples.

A few months ago, I gave a bit of a mixed review to Why Beautiful People Have More Daughters, a book about evolutionary psychology. It turns out that the main author, Satoshi Kanazawa, has taken his ideas to at least one ridiculous and terrifying extreme:

Imagine that, on September 11, 2001, when the Twin Towers came down, the President of the United States was not George W. Bush, but Ann Coulter. What would have happened then? On September 12, President Coulter would have ordered the US military forces to drop 35 nuclear bombs throughout the Middle East, killing all of our actual and potential enemy combatants, and their wives and children. On September 13, the war would have been over and won, without a single American life lost.

Yes, we need a woman in the White House, but not the one who’s running.

Uh, okay.

That's straight-on crazy talk (not to mention almost certainly incorrect in its results). Doesn't raise my opinion of his book, that's for sure.

On the other side of the evolutionary aisle are the producers of Expelled, a documentary claiming that the academic and scientific establishment are unfairly quashing free speech, by shunning researchers who promote intelligent design/creationism and other "critiques" of evolutionary biology. The movie is hosted by Ben Stein (probably best known as the teacher who said, "Bueller? Bueller?"), and also apparently argues that accepting evolution leads inevitably to atheism, which then (get this) led to the Stalinist pogroms and the Holocaust.

Uh, okay.

Among those interviewed in the film is PZ Myers, an American biology professor. He is also almost as well-known an atheist and staunch critic of religion and creationism as Richard Dawkins. He says that the producers were dishonest when asking him to appear in Expelled, claiming that its working title was Crossroads (although the expelledthemovie.com domain had apparently already been registered) and that it was a more objective examination of science and religion, rather than a project advocating for creationism. He has been scathingly critical of the film ever since.

Myers's interview ended up in the film anyway, which has been pre-screened a few times in the U.S. for largely hand-picked evangelical Christian audiences. One of those screenings just occurred in Minnesota, where Myers happened to be, so he signed up on the website for tickets for him, his family, and some friends. But when he showed up, the film's producer, who was also present and helped to organize the screening, barred him from entering.

His family and friends got in. One of those friends, also someone interviewed for the film under false pretenses?

Richard Dawkins. Yes, that one. No, really.

It's not turning into a good PR move for the movie's producers.

Labels: biology, controversy, creationism, intelligentdesign, movie, naturalselection, religion, science

20 March 2008

A billion years, or 600 million, give or take

How does evolution explain something like DNA and how it's decoded? Natural selection/chance-change over billions of years doesnt seem adequate to explain it. Are there other evolutionary mechanisms that might explain it?

Also, DNA seems very clearly to be instructions/information. From an evolutionary standpoint, would that be an illusion because [we humans interpret] what turns out to be chance results as something more meaningful and organized because the result kind of works?

Now, beware, since IANAEBOP (I Am Not An Evolutionary Biologist Or Philosopher). I do have pretty decent background in biology generally, it being my degree and all, and that means I need to understand natural selection well. So here goes my take.

What's chance, what isn't?

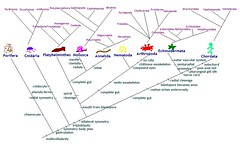

One of the issues here is that too often people talk about natural selection, including the initial appearance of DNA, as a random process. It's actually much the opposite: yes, mutations (i.e. the source material or "seeds" for evolutionary change) occur randomly, but the ones that persist because they lead to greater reproductive success are completely non-random. Non-random rules arising from natural processes filter out almost all the random stuff, leading to evolutionary processes that build upon themselves to generate new things.

But non-randomness doesn't have to imply conscious agency (at least I don't think so). Nor does it imply inevitability, or even directionality, really. If you rolled back the clock and started things over again with the first simple microorganisms, or at any later stage, even with essentially the same conditions, the result might very well have turned out very differently.

Evolution is a historical process, and like human history, there are so many inter-related, contingent influences going on that if we, say, started over again 75 million years ago with dinosaurs, even if an asteroid still wiped them out, there's no guarantee a human-like intelligence would arise later. Or if it did, that primates would necessarily be what did it.

Similarly, roll back farther, and would insects end up as the dominant multicellular animals again? Might woody flowering plants once more come to dominate over ferns and other now less common forms? Maybe not.

You can think of an analogy in something like the pattern of a streambed. Yes, the movement of individual water molecules or sand grains may be essentially random, but gravity and friction and a variety of other simple laws of nature, interacting in a very complex way, make it so that the result—the tree-like form of a drainage basin—has a very non-random structure. (If you drop something on earth, it falls down. If things were random, you'd have no way to predict which direction it would go.)

But, yet again, if you rolled back the clock and started the erosion process all over again, the stream's course might run in a very different direction. There would still be a tree-like structure constrained by natural laws, but the details of it would be totally different, so you couldn't plan to build a house or waterwheel or hydro dam in a particular location in advance.

The vastness of time

Another issue is time. Our brains really aren't well equipped to handle the kinds of time scales this stuff happens on. Something like DNA seems irredeemably complicated to have arisen by the hit-and-miss processes we're talking about. It's too well built. (Of course, the process also has its flaws, which is why people like me get cancer.) But we're used to watching stuff happen over the course of minutes or hours or days or weeks or months or years or maybe decades. The rise and fall of civilizations may take centuries. To us that seems like a long time.

Evidence seems to indicate that DNA first appeared pretty early on in earth's history. But it still took something like 600 million years, or maybe closer to a billion. Even if it were completely random (rather than a rule-driven process with random "seeds"), a lot of amazing things could happen totally by chance in 600 million years. And a lot of amazing things have happened in the 4 billion years since, some random, some not.

Humans have never witnessed a large asteroid impact on earth. As far as our actual experience (even on an evolutionary time scale) is concerned, it has never happened. But given enough time, tens or hundreds of millions of years, it pretty much must happen again, and it has happened several times before. So we can consider things impossible when, in the long run, they are inevitable, or at least probable.

Would DNA, or something like it, inevitably have arisen on earth, given enough time? We don't know, and can't know yet. That's why looking for unrelated life elsewhere is important: even if it's non-intelligent life, finding something that arose separately from life on earth would tell us that life-driving processes are at least reasonably likely in this universe.

Or maybe it really is nearly (but not quite) impossible, and it only happened here, once in all these billions of years there have been stars and planets. I hope not, but it could be.

Saving a step

Now, if you step back and ask why natural laws are structured in such a way that contingent, historical evolution can happen even once (or even why atoms and molecules can form at all in the first place, rather than just creating a universe that's nothing but a soup of plasma), that enters into realms of philosophy that I don't think we may ever be able to answer.

Many will answer that God must have made those rules. But if I think like that, I always have to ask: then what made the God (or gods) that could make those rules, and by what meta-rules? In my mind, it's the same problem, just one step further, so it isn't really an answer at all.

I'm comfortable enough thinking that life and the DNA that lets it propagate "just happened" (perhaps the greatest oversimplification it would ever be possible to make in any circumstance). And with observation and intelligence, we're able to understand very much about how things have happened since, without having to resort to supernatural explanations that, by definition, we cannot analyze because their rules must be inscrutable to us.

Labels: biology, evolution, history, intelligentdesign, naturalselection, religion, science, time

12 December 2007

Book Review: Why Beautiful People Have More Daughters

When I read Why Beautiful People Have More Daughters (buy at Amazon Canada

When I read Why Beautiful People Have More Daughters (buy at Amazon Canada or Amazon U.S.

), I wasn't angry, but I was uncomfortable—and not because one of the authors of this brand-new volume has been dead for almost five years. The book is a summary of the new field of evolutionary psychology, which shows that our evolutionary past strongly influences how humans think and behave today.

UPDATE March 2008: It looks like the main author if this book, Satoshi Kanazawa, is a bit of a wingnut, and also may not be analyzing many of his statistics correctly. I stand by my review of the book here, but my reservations listed in it (especially that there is very little information about what many of the mechanisms of evolutionary psychology are) have become stronger with new evidence. Overall, I'm likely to look at his work more skeptically from now on.

You can see why that might be discomfiting: most of us like to think that we're independent actors, making decisions based on thought, and maybe influenced by our upbringing and our environment. Sometimes we are. But Alan S. Miller (the dead one, who got the project started) and Satoshi Kanazawa (the living one, who finished it) show how often we're not. If you're a creationist or think that all evil derives from patriarchal traditions and corporate media, this book will bug the hell out of you.

Publisher Peguin sent me the book to review at the suggestion of Darren Barefoot. Although my biology degree is a couple of decades old now, I find nothing in the fundamental premises of evolutionary psychology shocking. It only makes sense that, like those of all other animals (more so, since we depend so much on it), our human brain has evolved along with the rest of our body, adapting through natural selection to our environment.

Or, as Miller and Kanazawa point out, to what used to be our environment. We behave, make decisions, and organize ourselves the way we do today largely because it helped our ancestors survive and reproduce in Africa tens of thousands of years ago.

That's where things get interesting, and where the discomfort and controversy arise. Take this, from page 95:

Of course, diamonds and flowers are beautiful, but they are beautiful precisely because they are expensive and lack intrinsic value, which is why it is mostly women who think that diamonds and flowers are beautiful. Their beauty lies in their inherent uselessness; this is why Volvos and potatoes are not beautiful.

A major foundation of evolutionary psychology is that sex drives everything. Or, more accurately, that the differences between how men's and women's genes propagate to our descendants drives much of our behaviour, from the obvious (mating rituals) to the puzzling (wars, jobs, when we choose to travel, what we like to buy). We're just like dogs bred to be aggressive or good at herding sheep, or like birds and fish adapted to flocking and schooling, or predators that survive because natural selection molded their brains to know how to stalk and pounce and kill.

The result is many provocative statements about human beings:

- Divorced parents with children are playing a game of chicken, and it is usually the mother who swerves.

- Men do everything they do in order to get laid.

- Any reasonably attractive young woman exercises as much power as does the (male) ruler of the world.

- Clear evidence of women's promiscuity [...] is the size and shape of men's genitals and what men do with them.

- We believe in God for the same reason that men constantly think that women are coming on to them.

- It is the wife's age, not the husband's, that prompts [a man's] "midlife crisis."

- Religion is not an adaptation in itself but a byproduct of other adaptations. [...] The human brain [...] is biased to perceive intentional forces behind a wide range of natural physical phenomena [and thus] to see the hand of God at work.

- Humans are [...] born racist and ethnocentric, and learn through socialization and education not to act on such innate tendencies.

- Sometimes [a woman saying] "no" [to sex] really does mean "try a little harder."

Why Beautiful People Have More Daughters makes a reasonable case, with lots of reputable research backing it up, that much of the conventional wisdom of psychology and sociology is wrong. The authors and their evolutionary psychologist colleagues argue that many of the improper, cruel, unfair, and evil things (or, for that matter, altruistic, pleasant, equitable, and good things) that people do are not the result of childhood environments, cultural traditions, or power structures.

Rather, our behaviours today—whether our current ethics and morals judge them good or bad—are the same behaviours that helped our ancestors' genes propagate, and thus are the reason we're here now.

Men killing their wives, other men, and their stepchildren. Women wanting, and men liking, long lustrous blonde hair. Religiously motivated suicide bombers being almost exclusively young male Muslims. People of both sexes preferring blue eyes to brown. Women choosing older and more powerful men as mates, but more attractive men as lovers. Essentially all human societies permitting either polygyny (men with multiple wives or mistresses) or serial polygyny (men who marry, divorce, and remarry, usually to younger women). Young single women often traveling abroad to experience the world while their male cohorts tend to stay home and hate foreigners. All have explanations in evolutionary psychology, some more solid than others.

The writing in the book is sometimes a bit manic, as if the authors were yanking me as a reader from example to example, saying, "Look! Look! We're right again!" Some of their conclusions come with lots of convincing scientific evidence, not to mention theoretical predictions about human behaviour that turn out to be true. But others are apparently pure speculation. I also think many of their explanations would have been clearer using the past tense, rather than the present, to keep the role of our ancestral environment clear.

They do show that beautiful people tend to have more daughters, and why that makes sense, but the physiological mechanism of how it happens wasn't clear to me. And neither the authors nor their editors seem to know what "begs the question" is actually supposed to mean.

To be fair, Miller and Kanazawa take pains to note that many of the things we do make little sense in the modern world (meaning the fast-changing one we've been in for the past 10,000 years or so, since the invention of agriculture). But because those behaviours evolved over hundreds of thousands or millions of years before that, we can't help ourselves. And the authors also highlight some areas—homosexuality, declining birthrates in industrialized countries, the willingness to become a soldier—that their field can't explain very well.

We still love sweet and fatty foods, which were once rare and precious but are now overabundant and giving us health problems. Similarly, we behave in ways that begat us more children when living in small groups of hunter-gatherers in a sub-tropical savannah, but which may not be of similar benefit in a world of fast cars, 80-year lifespans, high explosives, supermarkets, birth control, jet travel, antibiotics, and Internet dating.

What made me uncomfortable about the book is that, as a bleeding-heart leftie, of course I want to believe that we are not so driven and constrained by our evolutionary history. But I'm also trained in biology and—even more after reading Miller and Kanazawa—it's clear to me that, like other animals, we must be.

But what we do is not always what we ought to do: Why Beautiful People Have More Daughters reinforces repeatedly that facts (what is) do not determine morals (what should be). As a parallel, knowing that fleas spread bubonic plague doesn't make the plague desirable, and knowing that is key to combating the disease. But, conversely, the way we think things should be isn't necessarily the way they are either. Wanting human nature to compel us to treat each other fairly and well doesn't make that true. We have to find different reasons to make it happen, to overcome much of what is innate in us.

That is yet another lesson of the modern world that my brain, prehistoric as it is, has trouble handling.

Labels: biology, books, controversy, evolution, naturalselection, psychology

04 May 2007

Perhaps the best explanation of science I've ever seen

It's really long, but this court transcript (no really!) (via Pharyngula) provides a remarkably clear explanation, early on, of the processes the scientific community has developed over the past several hundred years to get better at figuring what's going on in the universe.

It's really long, but this court transcript (no really!) (via Pharyngula) provides a remarkably clear explanation, early on, of the processes the scientific community has developed over the past several hundred years to get better at figuring what's going on in the universe.

Later on, Dr. Kevin Padian, the paleontologist witness in question, goes into more detail about fossils, evolutionary biology, problems with proposals about intelligent design, and so on, with similar verve. I recommend you read the whole thing, but if you're short on time, just the Qualifications section will do.

Some quotes from that part:

I think the term "theory" [...] has to be looked at the way scientists consider it. A theory is not just something that we think of in the middle of the night after too much coffee and not enough sleep. That's an idea. And if you have a hypothesis, it's something that's a testable proposition, you can actually find some evidence that will help you to weigh it one way or the other.

A theory, in science [...] means a very large body of information that's withstood a lot of testing. It probably consists of a number of different hypotheses, many different lines of evidence. And it's something that is very difficult to slay with an ugly fact, as Huxley once put it, because it's just a complex body of work that's been worked on through time.

Gravitation is a theory that's unlikely to be falsified even if we saw something fall up. It would make us wonder, but we'd try to figure out what was going on there rather than just immediately dismiss gravitation.

[...]

For all the world, it looks like, you know, to us normal people, that the sun goes around the Earth. And for most people, it wouldn't make a difference whether the sun went around the Earth or it went around the moon, as Sherlock Holmes famously said to Watson. But when the renaissance scholars understood, found out that, in fact, the sun does not go around the Earth but the Earth and the planets go around the sun, it changed the way we look at the whole natural world in a very important and fundamental way.

And so part of the process of science is to discover things that will make a difference to our understanding of the natural world and not simply to reinforce appearances that are very difficult to test in an objective or testable sense.

And I really like this one:

If you are looking for direct ancestors, if you insist on an unbroken stream of intermediate fossils to document a case, I'm afraid that that's going to be difficult to get under any circumstances, but it's also equally impossible for the historical record of humans.

If we had to come up with evidence of every one of our direct linear or collateral ancestors and know everything about them, it would be impossible, yet we don't question the parentage of our friends and neighbors because they can't do that.

[...]

That seems like a very difficult standard of evidence to live up to. We can't do that with humans most of the time, and I'd be surprised if we could do it with animals that are 350, 400 million years old.

I just stayed up till almost three in the morning reading the whole thing, even in my chemo-sozzled state (it helps that I slept six hours earlier this evening). I do have to say that his slides could have used some work, but the strength of the words and ideas did their job, which was the point. Overall, it's a remarkable piece of written work—even more remarkable for being a transcript of courtroom speech.

Labels: biology, creationism, evolution, intelligentdesign, naturalselection, paleontology, science