Penmachine

04 April 2010

How did it get here?

A desiccated fruit husk, about 5 cm long, sat delicately on a nearby lawn this afternoon. I spotted it while walking the dog:

Did dry out like that naturally? I've seen similar veins-only leaf skeletons around, but this seems much more fragile:

I wonder what kind of fruit it was, and how it got there.

Labels: biology, photography, vancouver

15 March 2010

Studying for jobs that don't exist yet

After high school, there are any number of specialized programs you can follow that have an obvious result: training as an electrician, construction worker, chef, mechanic, dental hygienist, and so on; law school, medical school, architecture school, teacher college, engineering, library studies, counselling psychology, and other dedicated fields of study at university; and many others.

But I don't think most people who get a high school diploma really know very well what they want to do after that. I certainly didn't. And it's just as well.

At the turn of the 1990s, I spent two years as student-elected representative to the Board of Governors of the University of British Columbia, which let me get to know some fairly high mucky-muck types in B.C., including judges, business tycoons, former politicians, honourees of the Order of Canada, and of course high-ranking academics. One of those was the President of UBC at the time, Dr. David Strangway.

In the early '70s, before becoming an academic administrator, he had been Chief of the Geophysics Branch for NASA during the Apollo missions—he was the guy in charge of the geophysical studies U.S. astronauts performed on the Moon, and the rocks they brought back. And Dr. Strangway told me something important, which I've remembered ever since and have repeated to many people over the past couple of decades.

That is, when he got his physics and biology degree in 1956 (a year before Sputnik), no one seriously thought we'd be going to the Moon. Certainly not within 15 years, or probably anytime within Strangway's career as a geophysicist. So, he said to me, when he was in school, he could not possibly have known what his job would be, because NASA, and the entire human space program, didn't exist yet.

In a much less grandiose and important fashion, my experience proved him right. Here I am writing for the Web (for free in this case), and that's also what I've been doing for a living, more or less, since around 1997. Yet when I got my university degree (in marine biology, by the way) in 1990, the Web hadn't been invented. I saw writing and editing in my future, sure, since it had been—and remains—one of my main hobbies, but how could I know I'd be a web guy when there was no Web?

The best education prepares you for careers and avocations that don't yet exist, and perhaps haven't been conceived by anyone. Because of Dr. Strangway's story, and my own, I've always told people, and advised my daughters, to study what they find interesting, whatever they feel compelled to work hard at. They may not end up in that field—I'm no marine biologist—but they might also be ready for something entirely new.

They might even be the ones to create those new things to start with.

Labels: biology, education, memories, moon, school, science, vancouver, work

19 October 2009

Links of interest (2009-10-19):

From my Twitter stream:

- My dad had cataract surgery, and now that eye has perfect vision—he no longer needs a corrective lens for it for distance (which, as an amateur astronomer, he likes a lot).

- Darren's Happy Jellyfish (bigger version) is my new desktop picture.

- Ten minutes of mesmerizing super-slo-mo footage of bullets slamming into various substances, with groovy bongo-laden soundtrack.

- SOLD! Sorry if you missed out.

I have a couple of 4th-generation iPod nanos for sale, if you're interested. - Great backgrounder on the 2009 H1N1 flu virus—if you're at all confused about it, give this a read.

- The new Nikon D3s professional digital SLR camera has a high-gain maximum light sensitivity of ISO—102,400. By contrast, when I started taking photos seriously in the 1980s, ISO—1000 film was considered high-speed. The D3s can get the same exposure with 100 times less light, while producing perfectly acceptable, if grainy, results.

- Nice summary of how content-industry paranoia about technology has been wrong for 100 years.

- The Obama Nobel Prize makes perfect sense now.

- I like these funky fabric camera straps (via Ken Rockwell).

- I briefly appear on CBC's "Spark" radio show again this week.

- Here's a gorilla being examined in the same type of CT scan machine I use every couple of months. More amazing, though, is the mummified baby woolly mammoth. Wow.

- As I discovered a few months ago, in Canada you can use iTunes gift cards to buy music, but not iPhone apps. Apple originally claimed that was comply with Canadian regulations, but it seems that's not so—it's just a weird and inexplicable Apple policy. (Gift cards work fine for app purchases in the U.S.A.)

- We've released the 75th episode of Inside Home Recording.

- These signs from The Simpsons are indeed clever, #1 in particular.

- Since I so rarely post cute animal videos, you'd better believe that this one is a doozy (via Douglas Coupland, who I wouldn't expect to post it either).

- If you're a link spammer, Danny Sullivan is quite right to say that you have no manners or morals, and you suck.

- "Lock the Taskbar" reminds me of Joe Cocker, translated.

- A nice long interview with Scott Buckwald, propmaster for Mad Men.

Labels: animals, apple, biology, cartoon, geekery, humour, insidehomerecording, iphone, ipod, itunes, linksofinterest, nikon, photography, politics, science, surgery, television, video, web

11 September 2009

Lonely cactus

Time lapse video between 8:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m. I had hoped one of the flowers would open, but no such luck. Music is from my track "Striking Silver."

Labels: biology, home, photography, video

21 August 2009

Gnomedex 2009 day 1

My wife Air live blogged the first day's talks here at the 9th annual Gnomedex conference, and you can also watch the live video stream on the website. I posted a bunch of photos. Here are my written impressions.

My wife Air live blogged the first day's talks here at the 9th annual Gnomedex conference, and you can also watch the live video stream on the website. I posted a bunch of photos. Here are my written impressions.

Something feels a little looser, and perhaps a bit more relaxed, about this year's meeting. There's a big turnover in attendees: more new people than usual, more women, and a lot more locals from the Seattle area. More Windows laptops than before, interestingly, and more Nikon cameras with fewer Canons. A sign of tech gadget trends generally? I'm not sure.

As always, the individual presentations roamed all over the map, and some were better than others. For example, Bad Astronomer Dr. Phil Plait's talk about skepticism was fun, but also not anything new for those of us who read his blog. However, it was also great as a perfect precursor to Christine Peterson, who invented the term open source some years ago, but is now focused on life extension, i.e. using various dietary, technological, and other methods to improve health and significantly extend the human lifespan.

- Some stuff Dr. Plait said: "Skepticism is not cynicism." "You ask for the evidence [...] and make sure it's good." "Be willing to drop an idea if it's wrong. Yeah, that's tough." "Scientists screw it up as well." "It sucks to be fooled. You can lose your money. You can lose your life."

- Christine Peterson: "Moving is how you tell your body, I'm not dead yet!" "You see people hitting soccer balls with their heads. Would you do that with your laptop? And that's backed up!" (You might like my friend Bill's reaction on my Facebook page.)

As Lee LeFever quipped on Twitter, "The life extension talk is a great followup to the skepticism talk because it provides so many ideas of which to be skeptical." My thought was, her talk seemed like hard reductionist nerdery focused somewhere it may not apply very well. My perspective may be different because I have cancer; for me, life extension is just living, you know? But I also feel that not everything is an engineering problem.

There were a number of those dichotomies through the day. Some other notes I took today:

- Bre Pettis passed out 3D models "printouts" created with the MakerBot he helped design. "Bonus points for being able to print out your... uh... body... parts." "Oh my god, you should put this brain inside Walt Disney's head!" "What's black ABS plastic good for?" "Printing evil stuff."

- One of the most joyous things you'll ever see is a keen scientist really going off on his or her topic of specialty. Firas Khatib on FoldIt protein folding was one of those. For a given sequence of amino acids, the 3D protein structure with lowest free energy is likely to be its useful shape in biology—and his team made a video game to help people figure out optimum shapes, which in the long run can help cure diseases.

- Todd Friesen is a former search engine and website spammer. He had lots of interesting things today. In the world of white and black search engine optimization (SEO), SPAM = "Sites Positioned Above Mine." For spammers, RSS = "Really Simple Stealing" and thus spam blogs. Major techniques for web spammers: hacking pages, bribing people for access, forum posts and user profiles, comment spam. Pay Per Click = PPC = "Pills, Porn, and Casinos."

- I liked these from the Ignite super-fast presentations: "There are more social media non-gurus than social media gurus. Which means we can take them." On annual reports: "Imagine waiting A YEAR to find out what a company is doing."

We had a great trip down to Seattle via Chuckanut Drive with kk+ and Fierce Kitty. Tonight Air and I are sleeping in the Edgewater Hotel on Seattle's Pier 67, next to the conference venue, and tonight is also the 45th anniversary of the day the Beatles stayed in this same hotel and fished out the window.

Labels: anniversary, band, biology, conferences, geekery, gnomedex, history, music, science, travel

03 August 2009

When we are one

While researchers continue to study it, no one is yet sure why music moves us—how we can be affected emotionally by timed sequences of sounds. But we are. And while I play rock drums and love me some guitar, in my life, the most affecting music has been live, vocal, and collective.

Here's what I mean. One of the most astonishing things I've ever heard was the student choir at Magee, the high school where my wife teaches. Years ago I attended one of their concerts. They are, and have long been, an excellent choir. You can get a tiny sense of it from this video, but the sound doesn't do it justice (plus, Christmas carols in August sound weird):

That's a pale simulation of the true experience, though. At that concert years ago, held in the school's old auditorium, the singing was enveloping, and overpowering, from a full-size choir onstage. I almost cried from the sound alone.

Here's another example that had me getting teary for no good reason:

Thanks to Darren for the link.

Those of us who were around in the '80s best remember Bobby McFerrin from his annoying novelty song "Don't Worry, Be Happy." But he is a powerful and innovative jazz singer, who is at his best when co-opting audiences. When he does that, when the audience sings along as a mass of voices, I lose it. I nearly cried right now as I listened to the audience come in on "Ave Maria" at the link I just posted—and again at the end:

So beautiful. There's no way I could have held it in if I had been there.

I can think of other instances: Celso Machado and the crowd I was in at the Vancouver East Cultural Centre more than 15 years ago, or a packed-full B.C. Place Stadium singing the end of U2's "40" ("How long/To sing this song...") long after the band had left the stage in 1987. You get the idea.

Whatever the reasons we evolved to love music, one of its benefits is how it joins us. When you sing with a group, or even if you're just there when one is singing well, you become part of that group in a way that's almost impossible by any other means. You could be singing "Ave Maria" with McFerrin, or chanting "Die! Die! Die!" with Metallica, but when it happens, you're all one. We're all one.

Labels: biology, evolution, music, video

14 July 2009

Links of interest 2006-07-05 to 2006-07-13

Yup, still on a blog break. So, more of my selected Twitter posts, newest first:

- Vancouver to Whistler in one minute (okay, I cheated):

- We're in the mountains, but in a civilized way. Pool/hot tub, grocery store across the street, Wi-Fi. But, uh, there is mountain weather.

- Super-duper stop-motion movie with 60,000 photo prints (ad for Olympus, via Lisa Bettany and Photojojo). Chris Atherton points out that this follows Wolf and Pig.

- Okay camera nerds, here's some rangefinder pr0n for you.

- The stereotypically blingtastic (and boobtastic) video diminishes Karl Wolf's tolerable version of Toto's "Africa." (And I'm no Toto fan.) It's like a live-action Hot Chicks with Douchebags. Yes, the choirboy harmonies are actually kind of charming, but he's going P-Diddy on it in the end.

- In the storage closet, my kids found something of mine from 1976 that is EVEN GEEKIER than my U.S.S. Enterprise belt buckle:

Red shirts were available back then, as well as the blue Mr. Spock style, but I chose Kirk. Of course. - The only sounds I can hear right now: the dishwasher, the fan in the hallway, and the birds in the trees outside the window.

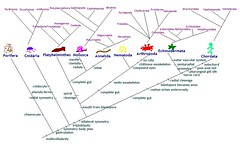

- During my biology degree, Platyhelminthes was a favourite organism name. Now there's a plush toy! (With 2 heads!!)

- When I used to busk with the band, our biggest victories were scaring away the holy rollers across the street (we got applause).

- Neat. When a ship is built, here are the differences between milestones: keel laying, christening, commissioning, etc.

- AutoTune the News #6. Even more awesome.

- Picked up kids from Aldergrove camp. Sadly, there was a terrible accident on the Port Mann Bridge. We took a long Langley/Surrey/New Westminster detour.

- Google's changing culture. Point: Google now has more employees than Microsoft did at launch of Windows 95.

- Time lapse: 8 hours from my front window in about 1 min 30 sec, made with my new Nikon D90 and free Sofortbild capture software (and iMovie):

Something like John Biehler's Nikon Coolpix P6000 is better for timelapse long term; the D90's mechanical shutter, which is rated for 100,000 uses, would wear out in less than 6 months if used for time lapse every day. P.S. Andy Gagliano pointed to a useful Macworld podcast about making time-lapse movies. - Depressing: most Internet Explorer 6 users use it at work, because they're not allowed to use another browser.

- These Christopher Walken impressions are way funnier than I expected.

- The way monkeys peel a banana shows us we've all been doing it the needlessly hard way all these years.

- Um... hot!

- Most appropriate Flash cartoon ever?

- Drinking whisky and Diet Dr. Pepper, watching MythBusters. Pretty mellow.

- A good photo is "not about the details or the subject. It's what your subconscious pulls out of it all without thinking."

- Just picked up another month's supply of horrible, nasty, vile, wonderful, beautiful, lifesaving anti-cancer pills. Thanks, Big Pharma Man.

- My wife tells me she's discovered a sure-fire tip for a gal to attract quality guys in public: carry a huge SLR camera over your shoulder.

- "For the great majority [...] blogging is a social activity, not an aspiration to mass-media stardom."

- Just talked to younger daughter (9) for first time after three days at summer camp. She's a little homesick, but having fun.

- I took a flight over a remote landscape:

- The 50 worst cars of all time (e.g. "The Yugo had the distinct feeling of something assembled at gunpoint").

- I haven't seen either Transformers movie, but that's okay, I saw this.

- Dan Savage: cheating on your spouse should now be known as "hiking the Appalachian Trail." Good point in the article too.

- You can still buy a station wagon with fake wood paneling!

- Train vs. tornado. It does not end well. Watch without fast-forward/scrubbing for maximum tension.

- Just lucked into a parking spot on Granville Island. Time for some lunch.

- Sent the kids off for a week of horse-riding camp today. Wife Air and I had sparkling wine in the garden. Vewwy vewwy quiet around here.

- Just sorted a bunch of CDs. Still several discs missing cases, and cases missing discs. I feel like a total '90s throwback.

- Rules of photography (via Alastair Bird).

- When did the standard Booth Babe uniform become cropped T-shirt and too-short schoolgirl kilt?

- Listening to "Kind of Blue." It's been awhile.

- "A two-year old is kind of like having a blender, but you don't have a top for it." - Jerry Seinfeld (via Ryan).

Labels: audio, biology, blog, cancer, chemotherapy, family, flickr, geekery, google, microsoft, movie, music, oceans, photography, sex, startrek, transportation, video, whistler

31 May 2009

Ignore Oprah's health advice, please

Like most TV shows, The Oprah Winfrey Show is entertaining as its first goal. And like most men, I've rarely enjoyed it much—because it's not aimed at me. That's fine.

But when she discusses health topics, Oprah can be dangerous (here's a single-page version of that long article). You have to infer from her show that on matters of health and medical science, Ms. Winfrey herself doesn't think critically, taking quackery just as seriously as, or more seriously than, anything with real evidence behind it. For every segment from Dr. Oz about eating better and getting more exercise, there seem to be several features on snake oil and magical remedies.

Vaccines supposedly causing autism, strange hormone therapy, offbeat cosmetic surgery, odious mystical crap like The Secret—she endorses them all. Yet even when the ones she tries herself don't seem to work for her, she doesn't backtrack or correct herself. And, almost pathologically, she remains obsessed with her weight despite all her other accomplishments.

Obviously, anyone who's taking their health advice solely from Oprah Winfrey, or any other entertainment personality, is making a mistake. However, I'd go further than that. Sure, watch Oprah for the personal life stories, the freakish tales, her homey demeanor, the cool-stuff giveaways if you want. But if she's dispensing health advice, ignore what she has to say. The evidence indicates to me that, while she may occasionally be onto something good, chances are she's promoting something ineffective or hazardous instead. Taking her advice is not worth the risk.

Labels: biology, controversy, media, science, television

23 April 2009

Big bugs and more

Photo Synthesis is a new blog started this month that will showcase science photography from around the Web. Right now it's almost all insect macrophotography (close-ups), but I'm sure there will be different stuff soon. At least I hope so—many people get creeped out by giant close-up pictures of ants, no matter how cool they are.

Labels: biology, photography, science

08 March 2009

A match of wits

Our problem woodpecker has returned, a month later, and seems undeterred by our protective chimney cages. We thought weather or the bird itself might have disturbed them, but no, they are still firmly in place. So the first move is to make the cages bigger—our Northern flicker may be large enough to get its beak right between the mesh to the metal.

Whenever I've heard the hammering (around 7 a.m., or 8 now that we're in Daylight Saving Time), I've made a quick leap into my bathrobe and slippers and tossed some pebbles from our yard onto the roof, which seems to scare it away each time. But, clever as this bird is, it doesn't seem to learn from the experience. As my dad said, "it's a match of wits." So far, the woodpecker is outwitting us.

Labels: animals, annoyances, biology, vancouver

07 February 2009

Return of the pecker

Remember this guy, the crazy Northern flicker woodpecker who used our kitchen stovepipe for a sounding board last March? Who woke us up every morning around 7 until we wrapped the metal chimney in bubble wrap? Who we thought was gone for good?

Well, he's back. Or was. Yesterday morning around 8 a.m., suddenly there was that familiar machine-gun metallic banging in the kitchen again. (The later hour makes sense, since it's over a month earlier in the season, so the sun is rising a bit later too, and I expect these guys time their noisemaking to the light.) I'm not sure if the bubble wrap fell off in the winter winds, or whether my dad, who lives in the other half of the duplex, removed it at some point.

UPDATE: My dad set up a nice solution to the problem, as shown in the photo. Let's see if it works.

UPDATE: My dad set up a nice solution to the problem, as shown in the photo. Let's see if it works.

When the pecker started pecking, I was in the kitchen, so I immediately turned on the noisy stove fan again, and the banging stopped. Encouragingly, there was nothing today. But listen, flicker, I have my ear out for you. You'd best mosey along before we take action again.

This is not a purely Vancouver problem by any means, as I found out from the Bad Astronomer in Colorado last year.

Labels: animals, annoyances, biology, vancouver

19 December 2008

Violence and sex

When you think about it a little, the two major things we prevent our children from seeing, sex and violence, are pretty weird. Not in themselves individually, but on how we fixate on them as a yin-yang pair. What's even weirder is that we treat sex (which, of the two, is certainly the good one) as the worst—even for adults.

Consider: When the great photographic website The Big Picture has a year-end picture retrospective, it warns us about violent images but still lets us see them, but doesn't include any sexual pictures at all, even though I'm sure 2008 included some amazing ones. And your local video rental store puts the porn in a hidden back room, but leaves the horror movies out on the public shelves.

I think I know why.

What I mean is, while we generally protect our kids from seeing extreme violence and gore, whether real or simulated, they still get exposed to a lot of lower-level stuff. Even for rather young children, everything from Mario pounding enemy characters with a hammer in videogames, to Bugs Bunny and Batman cartoons, to TV shows like Destroyed in Seconds (a guilty pleasure both for me and for my ten-year-old daughter) is fair game. As they get older, we're pretty much fine with letting them play more graphic games, watch CSI and Indiana Jones, and see shows where stuff (and people) get blowed up real good.

But apparently we're not going to let them see any sex. Nudity and sexuality are going to get a PG-13 or R or NC-17 from the ratings board a lot more easily than violence. And when was the last time a violent movie received an X rating? Surely any suggestion of sexuality between kids' videogame or TV characters would probably lead to a recall or cancellation—yet it's fine if they punch each other. The key example here? The infamous "hot coffee mod."

Here's my theory. For most people in developed western societies, any violence beyond accidents or schoolyard fisticuffs is pure fantasy. Unless you're a solider or maybe a gang member, or just perhaps a police officer in an extreme and unusual situation, chances are you will never kill or maim anyone on purpose in your entire life. You will never break someone's neck in hand-to-hand combat. You will never blow up a building or shoot down a plane. You will never aim a machine gun or a rocket launcher, or wield a sword in anger. You absolutely will not ever vaporize a planet.

And that's a good thing.

But nearly everyone, once they become adults, eventually has sex. Maybe a lot of it.

And that's also a good thing, or should be.

Children who see violence, especially exaggerated violence of the Donkey Kong or blowed-up-real-good variety, are seeing something they can fantasize about, but which they will never do. Children who see sex are seeing something they will almost certainly do eventually.

And that's why we adults think of sex as more dangerous for our kids. It's why we shield them from it for longer. It's why when we do discuss it at first, we have Serious Talks about the Human Reproductive System. And why we don't have Serious Talks about High Explosives.

Because sex is real, and important, and as we become adolescents we're wired by evolution to want it way more than we want to blow stuff up. So children need to learn about sex as a real thing, so they can make wise decisions when they get there. (How many of us, conversely, ever need to make any sort of decision about, say, wearing ear protection when firing a mortar in battle?)

I'm sure some sociologist has considered this already. However much the dichotomy between sex and violence makes sense, however, it's still pretty weird.

Don't even get me started on swearing.

Labels: biology, controversy, evolution, movie, psychology, sex, tv, videogames, violence

10 September 2008

Adam Savage laughs maniacally

I've never seen this effect (via Bad Astronomy) before:

Man, I just laughed and laughed out loud. No, you should not try it at home.

Labels: biology, geekery, humour, mythbusters, science

08 September 2008

Thinking about science

How strange that many people find science distant, or useless, or boring, or suspicious. I think the scientific impulse is naturally human, and that only the way some of us learn about it, and the way it is presented in our societies, is what mutes our interest.

How strange that many people find science distant, or useless, or boring, or suspicious. I think the scientific impulse is naturally human, and that only the way some of us learn about it, and the way it is presented in our societies, is what mutes our interest.

Today's link on Daring Fireball to Wired reminded me of that. Writer Clive Thompson says that:

Science isn't about facts. It's about the quest for facts.

A few months ago, web comic xkcd made a similar point in reference to MythBusters:

Ideas are tested by experiment. That is the core of science. Everything else is bookkeeping.

I learned lots of things from my science degree, but the key thing was that it's not a catalogue of knowledge, but a process to find that knowledge. A process that, fundamentally, is fun for the people who practice it. We should all understand that to be the foundation for the many things we have invented and come to know over the past few centuries.

Labels: biology, education, mythbusters, science

21 June 2008

Quandary: should I see "Expelled" or not?

Back in March I wrote about the dumb behaviour of the people who made the film Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed. Now, probably because of that posting and my other entries here about science, I've been invited by distributor KinoSmith to attend a press screening of the movie here in Vancouver next week. I'm wondering if I should bother to go.

Back in March I wrote about the dumb behaviour of the people who made the film Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed. Now, probably because of that posting and my other entries here about science, I've been invited by distributor KinoSmith to attend a press screening of the movie here in Vancouver next week. I'm wondering if I should bother to go.

Propagandumentary

First, some background about Expelled. It is a purported documentary, supposedly a Michael Moore–style critique of the current academic establishment of evolutionary biology. I enjoy a good intellectual debate, especially about topics as important to us as the development of life on earth, so if that's what Expelled really were, it might make an interesting film.

However, the evidence indicates that instead it is, in the words of New York Times reviewer Jeannette Catsoulis , "one of the sleaziest documentaries to arrive in a very long time [and] a conspiracy-theory rant masquerading as investigative inquiry." (That is the first line of her review.) Here, for instance, is a quote about Expelled from narrator Ben Stein:

Love of God and compassion and empathy leads you to a very glorious place. Science leads you to killing people.

It's fine for people to disagree, but a blanket line like "science leads you to killing people" is not only wrong, it's profoundly simplistic and inflammatory. Would religious people be likely to attend a movie promoted by lines like, "religion leads you to killing people"? I suspect, for instance, that many have been put off reading Christopher Hitchens's book God Is Not Great, with its chapter, "Religion Kills." (I haven't read it either, but not for that reason.)

Is it worth my time?

Okay, fine, so I'm not disposed to like the movie, but am I being closed-minded about it? Here's another issue. Totally beyond its mistaken premises, its misleading of interviewees, its senseless invocation of Hitler and Stalin as inevitable consequences of accepting natural selection, its plagiarism, and its promotion of intelligent design as a supposedly scientific idea instead of as a front for (mostly biblical) creationism, Expelled is also, by all indications, a lousy movie: poorly made, badly edited, patronizing, disorganized, and often dull.

Anyway, here's my quandary. I'm interested in finding out what all the fuss is about, so part of me thinks I should use the free double passes that arrived in the mail yesterday, and take three friends to see Expelled next Thursday. I wouldn't pay to see it, because I don't think the filmmakers deserve my money, but these are free tickets, and it's actually costing them for me to go.

On the other hand, I still remember seeing Highlander 2 back in 1991. That movie was so bad that it somehow made its predecessor worse: in my mind, it tainted the first Highlander film, which I had enjoyed. I get the feeling that Expelled is similarly bad, the kind of film that makes you wish you'd never seen it and had those few hours of your life back.

Probably not

We have a friend visiting from Australia for a couple of weeks, and our family would like to spend time with her. My daughters' final piano lesson is that same day. I suspect I have many better things to do, such as hanging out in my back yard, or maybe having a nap.

So, after my fine promotion here, does anyone want four free tickets to see Expelled next Thursday, June 26, 2008, at 7:00 p.m., at Tinseltown in downtown Vancouver? The tickets say, "Arrive early as theatre capacity is limited and seating is not guaranteed," by the way. Let me know if you want them, even if just for the hell of it. (Pun intended.)

Labels: biology, controversy, creationism, intelligentdesign, linkbait, movie, naturalselection, religion, science

21 May 2008

Links of interest (2008-05-21):

Chemo day today, so I'm in bed as usual, with Iron Chef America coming up in an hour. Some links:

- "Asperger's Syndrome has been a part of IT for as long as there's been IT. So why aren't we doing better by the Aspies among us?" (Via Tim Bray.)

- Finally! Apple Store Vancouver will open Saturday, May 24.

- Hancock may be the first original blockbuster movie idea in a long time—and it still has Will Smith! Nevertheless, I expect the new Indiana Jones opening on Thursday to be better, although there is blessedly very little original about it.

- While I've long thought the One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) project was a neat idea, I've also long had a sinking feeling that the people who put it together didn't really have a plan to make it work, especially once the computers were out in the field. It seems that may be true, according to the project's former director of security architecture (via Fake Steve), who writes, "now the company has half a million laptops in the wild, with no one even pretending to be officially in charge of deployment."

Labels: apple, biology, geekery, linksofinterest, movie, olpc, vancouver

07 May 2008

Rose petals and water drops

Ethan Gutmann at Ars Technica writes about the remarkable properties of rose petals when water drops land on them. Not only are rose petals superhydrophobic, like many plant leaves (water drops ball up on the surface), but unlike those leaves, those cool water drops also stick to the surface rather than rolling off.

Ethan Gutmann at Ars Technica writes about the remarkable properties of rose petals when water drops land on them. Not only are rose petals superhydrophobic, like many plant leaves (water drops ball up on the surface), but unlike those leaves, those cool water drops also stick to the surface rather than rolling off.

What makes that happen is the microscopic structure of the surface of the leaf. The petal surface is covered in tiny bumps, and the surfaces of those bumps are covered in even smaller, tiny tiny folds. But those tiny tiny folds are far enough apart that water at the bottom of a drop can get into them and stick to the surface; on most leaves, the folds are closer together, so the water can't stick and slides off.

Here's the research paper.

24 March 2008

Pecker

According to the provincial government, there are 12 species of woodpecker that appear at least occasionally in British Columbia, but only a few are common in the southern coastal areas outside the summer months. The one I've noticed most often is the pileated woodpecker, with its distinctive red swooshy head.

According to the provincial government, there are 12 species of woodpecker that appear at least occasionally in British Columbia, but only a few are common in the southern coastal areas outside the summer months. The one I've noticed most often is the pileated woodpecker, with its distinctive red swooshy head.

Right now, one of these guys is being a real goddamned pecker around our house.

UPDATE: I think I have unfairly maligned the pileated woodpecker. Although I still haven't spotted it directly, numerous reports from my readers and more careful listening to the infernal tapping tells me that our woodpecker is more likely to be a Northern flicker (I've updated the accompanying photo accordingly). In any case, a suggestion to burn some paper under our stove hood when we hear the tapping, so smoke sends the bird away, may be working. We'll see.

You see, it has decided that the metal chimney above our stove is an ideal target. I don't know why: if I were a woodpecker, I'd probably figure out fairly quickly that there aren't any tasty grubs living inside a kitchen vent. Then again, woodpecker skulls have evolved largely to withstand massive repeated impacts, not for smarts.

Now, imagine what it sounds like at, say 7:18 a.m. on Easter Monday, to have a woodpecker pounding away, Kalashnikov-like, on a highly-reverberant tube of metal that leads directly from the roof of your house into the amplifying stove hood in the middle of your kitchen, which is in the centre of the structure, right across the hall from the bedrooms. This has been going on intermittently for two or three weeks now at our place.

I stumbled out of bed and turned on the stove vent fan (which is very loud, being older than I am). No dice. So I wandered outside in bathrobe and bare feet and hucked a couple of small stones from our yard in the general direction of that part of the roof. I was surprised at my accuracy at such a bleary-eyed time of the morning.

There were some clattering noises, and I think I scared it off for now. It's likely pileated—the largest surviving woodpecker variety in North America, by the way—from the sound of its drumming, but I haven't actually seen it yet. I suppose if it persists in trying to find an insect colony in our kitchen chimney, it will eventually starve to death, but maybe it's clever enough to be working on some nearby trees too. I hope it avoids punching a bunch of holes in the aluminum, anyway, and that it gets the point (ha ha) eventually and moves on. Or I'll have to get better aim.

Labels: animals, annoyances, biology, vancouver

21 March 2008

Some people have bad ideas

I like to give people the benefit of the doubt, but sometimes they squander it. A couple of examples.

A few months ago, I gave a bit of a mixed review to Why Beautiful People Have More Daughters, a book about evolutionary psychology. It turns out that the main author, Satoshi Kanazawa, has taken his ideas to at least one ridiculous and terrifying extreme:

Imagine that, on September 11, 2001, when the Twin Towers came down, the President of the United States was not George W. Bush, but Ann Coulter. What would have happened then? On September 12, President Coulter would have ordered the US military forces to drop 35 nuclear bombs throughout the Middle East, killing all of our actual and potential enemy combatants, and their wives and children. On September 13, the war would have been over and won, without a single American life lost.

Yes, we need a woman in the White House, but not the one who’s running.

Uh, okay.

That's straight-on crazy talk (not to mention almost certainly incorrect in its results). Doesn't raise my opinion of his book, that's for sure.

On the other side of the evolutionary aisle are the producers of Expelled, a documentary claiming that the academic and scientific establishment are unfairly quashing free speech, by shunning researchers who promote intelligent design/creationism and other "critiques" of evolutionary biology. The movie is hosted by Ben Stein (probably best known as the teacher who said, "Bueller? Bueller?"), and also apparently argues that accepting evolution leads inevitably to atheism, which then (get this) led to the Stalinist pogroms and the Holocaust.

Uh, okay.

Among those interviewed in the film is PZ Myers, an American biology professor. He is also almost as well-known an atheist and staunch critic of religion and creationism as Richard Dawkins. He says that the producers were dishonest when asking him to appear in Expelled, claiming that its working title was Crossroads (although the expelledthemovie.com domain had apparently already been registered) and that it was a more objective examination of science and religion, rather than a project advocating for creationism. He has been scathingly critical of the film ever since.

Myers's interview ended up in the film anyway, which has been pre-screened a few times in the U.S. for largely hand-picked evangelical Christian audiences. One of those screenings just occurred in Minnesota, where Myers happened to be, so he signed up on the website for tickets for him, his family, and some friends. But when he showed up, the film's producer, who was also present and helped to organize the screening, barred him from entering.

His family and friends got in. One of those friends, also someone interviewed for the film under false pretenses?

Richard Dawkins. Yes, that one. No, really.

It's not turning into a good PR move for the movie's producers.

Labels: biology, controversy, creationism, intelligentdesign, movie, naturalselection, religion, science

20 March 2008

A billion years, or 600 million, give or take

How does evolution explain something like DNA and how it's decoded? Natural selection/chance-change over billions of years doesnt seem adequate to explain it. Are there other evolutionary mechanisms that might explain it?

Also, DNA seems very clearly to be instructions/information. From an evolutionary standpoint, would that be an illusion because [we humans interpret] what turns out to be chance results as something more meaningful and organized because the result kind of works?

Now, beware, since IANAEBOP (I Am Not An Evolutionary Biologist Or Philosopher). I do have pretty decent background in biology generally, it being my degree and all, and that means I need to understand natural selection well. So here goes my take.

What's chance, what isn't?

One of the issues here is that too often people talk about natural selection, including the initial appearance of DNA, as a random process. It's actually much the opposite: yes, mutations (i.e. the source material or "seeds" for evolutionary change) occur randomly, but the ones that persist because they lead to greater reproductive success are completely non-random. Non-random rules arising from natural processes filter out almost all the random stuff, leading to evolutionary processes that build upon themselves to generate new things.

But non-randomness doesn't have to imply conscious agency (at least I don't think so). Nor does it imply inevitability, or even directionality, really. If you rolled back the clock and started things over again with the first simple microorganisms, or at any later stage, even with essentially the same conditions, the result might very well have turned out very differently.

Evolution is a historical process, and like human history, there are so many inter-related, contingent influences going on that if we, say, started over again 75 million years ago with dinosaurs, even if an asteroid still wiped them out, there's no guarantee a human-like intelligence would arise later. Or if it did, that primates would necessarily be what did it.

Similarly, roll back farther, and would insects end up as the dominant multicellular animals again? Might woody flowering plants once more come to dominate over ferns and other now less common forms? Maybe not.

You can think of an analogy in something like the pattern of a streambed. Yes, the movement of individual water molecules or sand grains may be essentially random, but gravity and friction and a variety of other simple laws of nature, interacting in a very complex way, make it so that the result—the tree-like form of a drainage basin—has a very non-random structure. (If you drop something on earth, it falls down. If things were random, you'd have no way to predict which direction it would go.)

But, yet again, if you rolled back the clock and started the erosion process all over again, the stream's course might run in a very different direction. There would still be a tree-like structure constrained by natural laws, but the details of it would be totally different, so you couldn't plan to build a house or waterwheel or hydro dam in a particular location in advance.

The vastness of time

Another issue is time. Our brains really aren't well equipped to handle the kinds of time scales this stuff happens on. Something like DNA seems irredeemably complicated to have arisen by the hit-and-miss processes we're talking about. It's too well built. (Of course, the process also has its flaws, which is why people like me get cancer.) But we're used to watching stuff happen over the course of minutes or hours or days or weeks or months or years or maybe decades. The rise and fall of civilizations may take centuries. To us that seems like a long time.

Evidence seems to indicate that DNA first appeared pretty early on in earth's history. But it still took something like 600 million years, or maybe closer to a billion. Even if it were completely random (rather than a rule-driven process with random "seeds"), a lot of amazing things could happen totally by chance in 600 million years. And a lot of amazing things have happened in the 4 billion years since, some random, some not.

Humans have never witnessed a large asteroid impact on earth. As far as our actual experience (even on an evolutionary time scale) is concerned, it has never happened. But given enough time, tens or hundreds of millions of years, it pretty much must happen again, and it has happened several times before. So we can consider things impossible when, in the long run, they are inevitable, or at least probable.

Would DNA, or something like it, inevitably have arisen on earth, given enough time? We don't know, and can't know yet. That's why looking for unrelated life elsewhere is important: even if it's non-intelligent life, finding something that arose separately from life on earth would tell us that life-driving processes are at least reasonably likely in this universe.

Or maybe it really is nearly (but not quite) impossible, and it only happened here, once in all these billions of years there have been stars and planets. I hope not, but it could be.

Saving a step

Now, if you step back and ask why natural laws are structured in such a way that contingent, historical evolution can happen even once (or even why atoms and molecules can form at all in the first place, rather than just creating a universe that's nothing but a soup of plasma), that enters into realms of philosophy that I don't think we may ever be able to answer.

Many will answer that God must have made those rules. But if I think like that, I always have to ask: then what made the God (or gods) that could make those rules, and by what meta-rules? In my mind, it's the same problem, just one step further, so it isn't really an answer at all.

I'm comfortable enough thinking that life and the DNA that lets it propagate "just happened" (perhaps the greatest oversimplification it would ever be possible to make in any circumstance). And with observation and intelligence, we're able to understand very much about how things have happened since, without having to resort to supernatural explanations that, by definition, we cannot analyze because their rules must be inscrutable to us.

Labels: biology, evolution, history, intelligentdesign, naturalselection, religion, science, time

17 February 2008

Blogging about research, and a new way to buy my album

There's a ton of neat stuff over at ResearchBlogging.org, a site that aggregates blog posts about peer-reviewed research in the social and natural sciences. You can subscribe to an RSS feed for new posts, including citations. The blog from ResearchBlogging is also interesting, especially when it talks about controversies concerning what counts as legitimate research.

There's a ton of neat stuff over at ResearchBlogging.org, a site that aggregates blog posts about peer-reviewed research in the social and natural sciences. You can subscribe to an RSS feed for new posts, including citations. The blog from ResearchBlogging is also interesting, especially when it talks about controversies concerning what counts as legitimate research.

Some posts I've really enjoyed based on my biology degree background have been those at Pharyngula about how vertebrate eyes evolved (which, incidentally, firmly debunks the claim creationists frequently make that eyes are too complex to have evolved biologically) and how plant and animal development differ (and why the differences support the indications that our last common ancestor with plants was most likely a single-celled organism living more than 1.6 billion years ago).

And check out this lovely map of the human impact on marine ecosystems, which includes these nasty new marine dead zones off the west coast of North America, not far from where I live.

On a totally unrelated topic, my album Penmachine Sessions, which has been sold out in physical CD form since the middle of last year, is available in a whole bunch of digital forms, with the latest being the Amazon MP3 Store. It might be the best place to buy the album of all, since you get unrestricted, high-quality (256 kbps) MP3 files (that's better than the MP3 files I made for myself!) for only 99 cents each, or $8.99 for the whole album. I think it may only be available to U.S. customers for now, unfortunately.

No, I have no idea at all why Amazon labels my album as "explicit"—particularly because it is almost entirely instrumental music with no words!

Labels: biology, blog, controversy, creationism, evolution, music, science

12 December 2007

Book Review: Why Beautiful People Have More Daughters

When I read Why Beautiful People Have More Daughters (buy at Amazon Canada

When I read Why Beautiful People Have More Daughters (buy at Amazon Canada or Amazon U.S.

), I wasn't angry, but I was uncomfortable—and not because one of the authors of this brand-new volume has been dead for almost five years. The book is a summary of the new field of evolutionary psychology, which shows that our evolutionary past strongly influences how humans think and behave today.

UPDATE March 2008: It looks like the main author if this book, Satoshi Kanazawa, is a bit of a wingnut, and also may not be analyzing many of his statistics correctly. I stand by my review of the book here, but my reservations listed in it (especially that there is very little information about what many of the mechanisms of evolutionary psychology are) have become stronger with new evidence. Overall, I'm likely to look at his work more skeptically from now on.

You can see why that might be discomfiting: most of us like to think that we're independent actors, making decisions based on thought, and maybe influenced by our upbringing and our environment. Sometimes we are. But Alan S. Miller (the dead one, who got the project started) and Satoshi Kanazawa (the living one, who finished it) show how often we're not. If you're a creationist or think that all evil derives from patriarchal traditions and corporate media, this book will bug the hell out of you.

Publisher Peguin sent me the book to review at the suggestion of Darren Barefoot. Although my biology degree is a couple of decades old now, I find nothing in the fundamental premises of evolutionary psychology shocking. It only makes sense that, like those of all other animals (more so, since we depend so much on it), our human brain has evolved along with the rest of our body, adapting through natural selection to our environment.

Or, as Miller and Kanazawa point out, to what used to be our environment. We behave, make decisions, and organize ourselves the way we do today largely because it helped our ancestors survive and reproduce in Africa tens of thousands of years ago.

That's where things get interesting, and where the discomfort and controversy arise. Take this, from page 95:

Of course, diamonds and flowers are beautiful, but they are beautiful precisely because they are expensive and lack intrinsic value, which is why it is mostly women who think that diamonds and flowers are beautiful. Their beauty lies in their inherent uselessness; this is why Volvos and potatoes are not beautiful.

A major foundation of evolutionary psychology is that sex drives everything. Or, more accurately, that the differences between how men's and women's genes propagate to our descendants drives much of our behaviour, from the obvious (mating rituals) to the puzzling (wars, jobs, when we choose to travel, what we like to buy). We're just like dogs bred to be aggressive or good at herding sheep, or like birds and fish adapted to flocking and schooling, or predators that survive because natural selection molded their brains to know how to stalk and pounce and kill.

The result is many provocative statements about human beings:

- Divorced parents with children are playing a game of chicken, and it is usually the mother who swerves.

- Men do everything they do in order to get laid.

- Any reasonably attractive young woman exercises as much power as does the (male) ruler of the world.

- Clear evidence of women's promiscuity [...] is the size and shape of men's genitals and what men do with them.

- We believe in God for the same reason that men constantly think that women are coming on to them.

- It is the wife's age, not the husband's, that prompts [a man's] "midlife crisis."

- Religion is not an adaptation in itself but a byproduct of other adaptations. [...] The human brain [...] is biased to perceive intentional forces behind a wide range of natural physical phenomena [and thus] to see the hand of God at work.

- Humans are [...] born racist and ethnocentric, and learn through socialization and education not to act on such innate tendencies.

- Sometimes [a woman saying] "no" [to sex] really does mean "try a little harder."

Why Beautiful People Have More Daughters makes a reasonable case, with lots of reputable research backing it up, that much of the conventional wisdom of psychology and sociology is wrong. The authors and their evolutionary psychologist colleagues argue that many of the improper, cruel, unfair, and evil things (or, for that matter, altruistic, pleasant, equitable, and good things) that people do are not the result of childhood environments, cultural traditions, or power structures.

Rather, our behaviours today—whether our current ethics and morals judge them good or bad—are the same behaviours that helped our ancestors' genes propagate, and thus are the reason we're here now.

Men killing their wives, other men, and their stepchildren. Women wanting, and men liking, long lustrous blonde hair. Religiously motivated suicide bombers being almost exclusively young male Muslims. People of both sexes preferring blue eyes to brown. Women choosing older and more powerful men as mates, but more attractive men as lovers. Essentially all human societies permitting either polygyny (men with multiple wives or mistresses) or serial polygyny (men who marry, divorce, and remarry, usually to younger women). Young single women often traveling abroad to experience the world while their male cohorts tend to stay home and hate foreigners. All have explanations in evolutionary psychology, some more solid than others.

The writing in the book is sometimes a bit manic, as if the authors were yanking me as a reader from example to example, saying, "Look! Look! We're right again!" Some of their conclusions come with lots of convincing scientific evidence, not to mention theoretical predictions about human behaviour that turn out to be true. But others are apparently pure speculation. I also think many of their explanations would have been clearer using the past tense, rather than the present, to keep the role of our ancestral environment clear.

They do show that beautiful people tend to have more daughters, and why that makes sense, but the physiological mechanism of how it happens wasn't clear to me. And neither the authors nor their editors seem to know what "begs the question" is actually supposed to mean.

To be fair, Miller and Kanazawa take pains to note that many of the things we do make little sense in the modern world (meaning the fast-changing one we've been in for the past 10,000 years or so, since the invention of agriculture). But because those behaviours evolved over hundreds of thousands or millions of years before that, we can't help ourselves. And the authors also highlight some areas—homosexuality, declining birthrates in industrialized countries, the willingness to become a soldier—that their field can't explain very well.

We still love sweet and fatty foods, which were once rare and precious but are now overabundant and giving us health problems. Similarly, we behave in ways that begat us more children when living in small groups of hunter-gatherers in a sub-tropical savannah, but which may not be of similar benefit in a world of fast cars, 80-year lifespans, high explosives, supermarkets, birth control, jet travel, antibiotics, and Internet dating.

What made me uncomfortable about the book is that, as a bleeding-heart leftie, of course I want to believe that we are not so driven and constrained by our evolutionary history. But I'm also trained in biology and—even more after reading Miller and Kanazawa—it's clear to me that, like other animals, we must be.

But what we do is not always what we ought to do: Why Beautiful People Have More Daughters reinforces repeatedly that facts (what is) do not determine morals (what should be). As a parallel, knowing that fleas spread bubonic plague doesn't make the plague desirable, and knowing that is key to combating the disease. But, conversely, the way we think things should be isn't necessarily the way they are either. Wanting human nature to compel us to treat each other fairly and well doesn't make that true. We have to find different reasons to make it happen, to overcome much of what is innate in us.

That is yet another lesson of the modern world that my brain, prehistoric as it is, has trouble handling.

Labels: biology, books, controversy, evolution, naturalselection, psychology

10 December 2007

Surfing molluscs

We have aquatic snails in our fish tank, rather by accident. They came in on one of the plants we bought for the aquarium, and they multiply like crazy.

We have aquatic snails in our fish tank, rather by accident. They came in on one of the plants we bought for the aquarium, and they multiply like crazy.

As someone who specialized in marine invertebrates for my biology degree, I rather like these little molluscs. They keep the sides of the tank spotlessly clean. They move surprisingly quickly (for snails). There are, however, often too many of them—they outnumber the fish by at least an order of magnitude—so we occasionally have to scoop some out and, uh, send them to greener pastures. (I have no doubt that things are greener, not to mention sludgier, in the Greater Vancouver sewer system.)

The snails perform one stunt that I hadn't seen before. Often they will make their way to the top of the aquarium and then "surf" upside down on the underside of the water's surface, riding the currents created by the tank filter. Sometimes one will circulate around for several minutes, its muscular foot flat against the surface tension, then it will either stick to a side or drift down to the gravel at the bottom to start trucking its way around again.

It's pretty cool, and probably the fastest these creatures will ever travel in their lives. Unless they get to visit the sewer someday, I guess.

Labels: biology, extremesports, family, fish, invertebrates

23 November 2007

A whale straight in the eye

Blue whales are so large that, in most oceans in the world, if you were underwater with an adult one, you wouldn't be able to see one end from the other.

Blue whales are so large that, in most oceans in the world, if you were underwater with an adult one, you wouldn't be able to see one end from the other.

If one were swimming in the nutrient-rich waters near Vancouver, for instance, the body of the whale would disappear into the distance because the visibility is too obscured (by plankton and other things in the water itself) to take in the animal's entire 30-metre length—about the same as three typical shipping containers.

But if you want to see what it would be like to examine a blue whale up close, life size, here's a web page (via Mirabilis) where you can do it.

Labels: animals, biology, environment, oceans

17 October 2007

Pity about James Watson

UPDATE: I think Angela Gunn of USA Today (whom I think I met briefly back in 2005) has the best followup on Watson this week, and as a bonus she's actually read his new book right through. The Daily Telegraph has also termed his comments a symptom of "Nobel Syndrome."

The photo here is of James Watson, one of the co-discoverers of the structure of DNA and winner of the Nobel Prize for it. He also appears to be quite the bigot, stating this week that he is:

The photo here is of James Watson, one of the co-discoverers of the structure of DNA and winner of the Nobel Prize for it. He also appears to be quite the bigot, stating this week that he is:

...inherently gloomy about the prospect of Africa [because] all our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours—whereas all the testing says not really.

In other words, he thinks black people are just inevitably dumber than white people. He's wrong, quite wrong, in ways that many people have demonstrated over many decades.

His comments have set off quite a storm, as you would expect, and they are also far from his first controversial statements. I find his remarks both ignorant of the science on the subject (odd, given his supposed expertise) and morally repugnant, regardless of his esteemed achievements. I hope you do too.

Labels: biology, controversy, evolution, jameswatson, racism, science

30 May 2007

Rejecting reality and believing falsehood

One of my recurring themes here recently has been the ways our Old World primate brains make it difficult for us humans to understand many basic things, including probability and risk, geological time, contingency, extremly large- or small-scale events, and so forth.

Here's another one, an excellent psychology article about why we resist some scientific ideas more than others (via Pharyngula). Coincidentally, Harvard history of science professor Steven Shapin addresses a similar topic on the CBC Ideas podcast this week called "Testing Science" (MP3 file). Essentially, research shows that...

...even one year-olds possess a rich understanding of both the physical world (a "naive physics") and the social world (a "naive psychology"). [...] These intuitions give children a head start when it comes to understanding and learning about objects and people. But these intuitions also sometimes clash with scientific discoveries about the nature of the world, making certain scientific facts difficult to learn.

However, some concepts don't work that way, even when they are far from obvious. For example:

[The existence of germs and electricity] is generally assumed in day-to-day conversation and is not marked as uncertain; nobody says that they "believe in electricity." Hence even children and adults with little scientific background believe that these invisible entities really exist.

That's interesting, because our evidence for those things is pretty indirect, however pervasive: light switches and televisions and computers work, and washing your hands helps prevent infection. But most people have never seen a germ, never mind an electron. It would seem, purely objectively, that being able to look at rock strata in a highway cut, or watch the patterns of a coin flipped over and over, or observe the similarities and differences between chimpanzees and humans at the zoo, or hummingbirds and dragonflies in the garden, would make concepts like deep time and randomness and biological evolution easier to understand than electricity or germ theory.

Yet they are not. Our brains are remarkable things, and one of the most remarkable things about them is that we can, if we work at it as we grow up and throughout our lives, help ourselves get around our own cognitive limitations.

Labels: biology, evolution, psychology, science

24 May 2007

Pac-Man skeleton

This is both scary looking and too awesome...

...but I think most people, like me, never thought that Pac-Man had teeth. (Via Bidi.)

Labels: biology, evolution, games, geekery, pacman, science, videogames

19 May 2007

Feeling safe vs. being safe

Via netdud, I read once again another highly sensible article from Bruce Schneier about how badly we as a society usually react to security threats. It's a strange contrast to, and yet also a perfect demonstration of, my post yesterday about the Air India bombing, where it seems that direct, credible, likely threats didn't receive the attention they deserved—while today we confiscate nail clippers and remove shoes at airport security in a way that is likely totally ineffective.

I've written repeatedly about this stuff over the years here on my blog: about how our African savannah brains are poorly equipped to deal with the risks we face in the modern world.

But in another essay, Schneier also makes the point that "security theatre," as he terms it, isn't always wasteful, because sometimes it makes our perception of our security more closely match the statistical reality. That is rare—most of the time it throws money away and skews our perceptions further from reality—but we do also have to take into account how safe we feel, as well as how safe we are.

Labels: biology, evolution, probability, psychology, security, terrorism

04 May 2007

Perhaps the best explanation of science I've ever seen

It's really long, but this court transcript (no really!) (via Pharyngula) provides a remarkably clear explanation, early on, of the processes the scientific community has developed over the past several hundred years to get better at figuring what's going on in the universe.

It's really long, but this court transcript (no really!) (via Pharyngula) provides a remarkably clear explanation, early on, of the processes the scientific community has developed over the past several hundred years to get better at figuring what's going on in the universe.

Later on, Dr. Kevin Padian, the paleontologist witness in question, goes into more detail about fossils, evolutionary biology, problems with proposals about intelligent design, and so on, with similar verve. I recommend you read the whole thing, but if you're short on time, just the Qualifications section will do.

Some quotes from that part:

I think the term "theory" [...] has to be looked at the way scientists consider it. A theory is not just something that we think of in the middle of the night after too much coffee and not enough sleep. That's an idea. And if you have a hypothesis, it's something that's a testable proposition, you can actually find some evidence that will help you to weigh it one way or the other.

A theory, in science [...] means a very large body of information that's withstood a lot of testing. It probably consists of a number of different hypotheses, many different lines of evidence. And it's something that is very difficult to slay with an ugly fact, as Huxley once put it, because it's just a complex body of work that's been worked on through time.

Gravitation is a theory that's unlikely to be falsified even if we saw something fall up. It would make us wonder, but we'd try to figure out what was going on there rather than just immediately dismiss gravitation.

[...]

For all the world, it looks like, you know, to us normal people, that the sun goes around the Earth. And for most people, it wouldn't make a difference whether the sun went around the Earth or it went around the moon, as Sherlock Holmes famously said to Watson. But when the renaissance scholars understood, found out that, in fact, the sun does not go around the Earth but the Earth and the planets go around the sun, it changed the way we look at the whole natural world in a very important and fundamental way.

And so part of the process of science is to discover things that will make a difference to our understanding of the natural world and not simply to reinforce appearances that are very difficult to test in an objective or testable sense.

And I really like this one:

If you are looking for direct ancestors, if you insist on an unbroken stream of intermediate fossils to document a case, I'm afraid that that's going to be difficult to get under any circumstances, but it's also equally impossible for the historical record of humans.

If we had to come up with evidence of every one of our direct linear or collateral ancestors and know everything about them, it would be impossible, yet we don't question the parentage of our friends and neighbors because they can't do that.

[...]

That seems like a very difficult standard of evidence to live up to. We can't do that with humans most of the time, and I'd be surprised if we could do it with animals that are 350, 400 million years old.

I just stayed up till almost three in the morning reading the whole thing, even in my chemo-sozzled state (it helps that I slept six hours earlier this evening). I do have to say that his slides could have used some work, but the strength of the words and ideas did their job, which was the point. Overall, it's a remarkable piece of written work—even more remarkable for being a transcript of courtroom speech.

Labels: biology, creationism, evolution, intelligentdesign, naturalselection, paleontology, science