Penmachine

18 April 2010

The Fish House, 45 years later

On Saturday, April 17, 1965, my parents were married in St. Andrews Wesley Church on Burrard Street in downtown Vancouver. They held their reception that evening, in a building constructed as the Stanley Park Sports Pavilion in 1930. Today it's the home of the Fish House restaurant.

Last night, 45 years later, also on a Saturday, they returned to the Fish House for an anniversary dinner:

My wife Air, our daughter Marina, and I were happy to join them. (Our younger daughter was at a friend's birthday sleepover.)

I haven't been to the Fish House in at least 15 years, but I won't wait that long again. The food was great—with the added benefit of legacy dishes imported from Vancouver's legendary and recently-closed seaside restaurant, the Cannery. The salmon, prawns, and scallops I ate were excellent, but the rare tuna steak that Air ordered (and which she let me try) was extraordinary.

In August, Air and I will mark 15 years since our wedding in 1995. I hope we can make it to 45, however unlikely my health makes that seem right now. In the meantime, happy anniversary, Mom and Dad. Thanks for inviting us along.

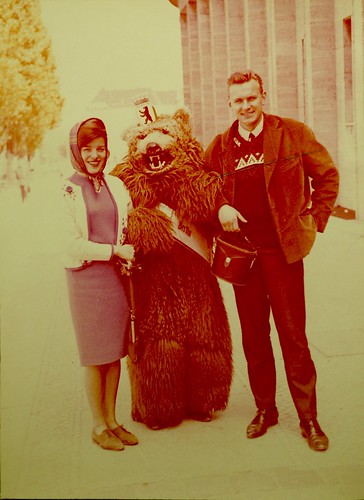

P.S. Here were my parents later in 1965, in Berlin, on their honeymoon:

Labels: anniversary, family, food, restaurant, review, vancouver

14 February 2010

Happy birthday, Marina

February 14 has many meanings for me. It's Valentine's Day, of course—the 16th my wife Air and I have spent together. It is also our daughter Marina's 12 birthday. But with the Winter Olympics here in Vancouver, including Canada's first gold medal of the event, there's extra resonance, since one of our athletes won gold on the day Marina was born back in 1998 too.

February 14 has many meanings for me. It's Valentine's Day, of course—the 16th my wife Air and I have spent together. It is also our daughter Marina's 12 birthday. But with the Winter Olympics here in Vancouver, including Canada's first gold medal of the event, there's extra resonance, since one of our athletes won gold on the day Marina was born back in 1998 too.

Air had a long, hard labour that February, and with the Nagano Olympics half a world away, we were able to watch many events live as a distraction in the middle of the night. Now our daughter is nearly a teenager, with her own mobile phone and Twitter account. (I got my first mobile phone when Air was pregnant that first time. I was 28. And getting on Twitter? I was 37.)

Happy birthday, Marina. Happy Valentine's Day to my lovely, wonderful, resourceful, smart, sharp, and stylish wife Air. Happy Olympics to all of you too.

Labels: anniversary, birthday, family, holiday, love, olympics, party

01 February 2010

My 13 jobs

This month, February 2010, marks three fricking years since I first went on disability leave for cancer treatment. (And, incidentally, since we got our Nintendo Wii.) This got me thinking about all the jobs I've had in my life, starting back when I was still in high school.

It turns out that I've worked for 13 organizations, if you include my own company when I was freelancing. I did not enjoy every job, but each taught me something:

| Year(s) | Job | Lesson |

|---|---|---|

| 1985? | Graveyard-shift self-serve gas station attendant | Don't be a graveyard-shift self-serve gas station attendant. Also, burnt coffee smells really bad. |

| 1988 | Park naturalist | Science is fun, five-year-olds aren't patient, but summer jobs are a great place to meet your future wife. Also, avoid flipping your canoe. |

| 1989 | Science centre floor staff | Science is fun, but you'll spend most of your time telling people where the bathrooms are. |

| 1990 | Student handbook editor | Choose your fonts carefully, and people never get things in on deadline. |

| 1991 | Student society admin assistant | It's a long way to pick up your printouts across campus when you type them on a mainframe computer. |

| 1991 | English conversation coach | Japanese girls definitely interested in learning English; Japanese boys (who smoke like chimneys), not so much. |

| 1992–1994 | Student issues researcher | Creating your own job is great, but it sure would be nice to have an office with a window. |

| 1994–1995 | Full-time rock 'n' roll drummer | Playing live music onstage is often awesome. Everything offstage, however, usually sucks. |

| 1995–1996 | Magazine advertising assistant | No matter how nice your co-workers, a bad boss can ruin the whole experience. |

| 1996–2001 | Various software company jobs, from developers' assistant to webmaster | Even if you know almost nothing about how to do it, when someone asks you if you want to run a website, it's still worthwhile to say "sure!" |

| 2001–2003 | Freelance technical writer and editor | The paperwork to run your own business is immensely boring. |

| 2001–2003 | Semi–full-time rock 'n' roll drummer | Rock is more fun when you mostly stay in town and get paid better. |

| 2003–2007 | Communications Manager, Navarik | Working with friends can be a good thing, especially when they have good ideas. Oh, and a decent extended-health plan is really, really important. |

In the late '80s, I also helped my friend Chris install alarm systems in people's homes and businesses, but while I got some money from it, it wasn't quite a job in the same way. It was more like when I helped him repair cars and resell them around the same time. Though in those cases, I did learn that I dislike crawling around in fibreglass-filled attics running wires, and that I'm not too fond of all the grease, gunk, and rust involved in auto work either.

Labels: anniversary, band, cancer, editing, ego, memories, navarik, neurotics, nintendo, wii, work, writing

08 January 2010

A funny thing happened to me on the way to the chemo ward

Today is exactly three years since I found out I have cancer. I had it longer than that, at least since the spring of 2006, but that's when I knew. Three years of hell, total hell. So, another cancer post—but that won't be all I write here, just as it hasn't been since January 2007.

Chemotherapy is weird. Not the concept of it, really, which is pretty simple: poison your body with chemicals that try to poison cancer cells more than healthy cells. But being on chemotherapy is weird.

Every combination of chemo drugs is targeted a particular variety of cancer, and every person gets different side effects depending on the drugs and on our own physiology. I've been through numerous rounds of different types of chemo in the past three years. The stereotypes of nausea, weight loss, and hair falling out are true—all too true in some cases, such as when I barfed up my entire breakfast yesterday morning—but they are not universal. I've only had to shave my head once (so far), for instance.

But most chemo regimens have a variety of other, much stranger side effects too. There was that brutal acne I had a couple of summers ago, for instance. The warnings to avoid anything containing grapefruit or starfruit in other instances (though oranges, lemons, limes, and other citrus were fine). Strange black lines developing in my fingernails. Sensitivity to sunlight. Lots of bizarre and nasty intestinal side effects that sometimes had me in the bathroom for three or four hours at a time. And so on.

This time around, I have several different oddball side effects at the same time:

- My skin is remarkably sensitive to cold. On Christmas Eve, some of my family went for a walk for about 20 minutes. The weather was just around the freezing mark, and I was wearing a hat, gloves, and a scarf wrapped around my face. But when we got back to my aunt and uncle's house, the tip of my nose and my fingers felt almost frostbitten, burning until they warmed up. I have to be careful simply taking cold drinks out of the fridge.

- Speaking of which, I can't drink cold liquids either. For instance, I had some orange juice out of the fridge last week. No one but me in our house likes juice with pulp, so I was surprised when this one was full of pulp. Except it wasn't—my mouth and throat were reacting to the cold and making it feel like the drink was full of globs of pulp, even though it was clear. Then it hurt.

- The knuckles on both my hands are dry and the skin has darkened. When I put my hands palm down, they have stripes of brown pigment across the fingers.

- Cuts and bruises take longer to heal. I drew blood during some Ikea furniture disassembly more than a week ago, and it still hurts as the scab seals up.

- I have nausea, but other than when I'm actually on the chemo, it's wildly unpredictable. That breakfast I lost yesterday? A minute before I vomited, I felt fine. Same a minute later. And one of the only things I can eat no matter how I feel is Cheese Pleesers—those extruded cheese puff snacks.

- Then there are my feet. They're not exactly sore, but my soles are extra-sensitive, almost as if they have blisters on them. Sometimes. Most often I don't notice it, but I can't stand having a bathmat in the tub when I shower because it irritates my feet, and I wear socks pretty much all the time otherwise, even to sleep.

There may be more symptoms coming, I don't really know. But it's weird. And exhausting.

Labels: anniversary, cancer, chemotherapy, pain

24 November 2009

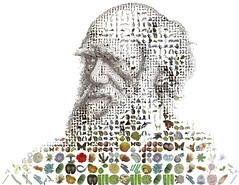

"The Origin" at 150

I wrote about it in much more detail back in February, but today is the actual 150th anniversary of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species, which was first published on November 24, 1859. That was more than two decades after Darwin first formulated his ideas about evolution by natural selection.

I wrote about it in much more detail back in February, but today is the actual 150th anniversary of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species, which was first published on November 24, 1859. That was more than two decades after Darwin first formulated his ideas about evolution by natural selection.

Some have called The Origin the most important book ever written, though of course many would dispute that. It's certainly up there on the list, and unequivocally on top for the field of biology. Darwin, along with others like Galileo, radically changed our perceptions about our place in the universe.

But Darwin was a scientist, not an inventor: he discovered natural selection, but did not create it. We honour him for being smart and tenacious, for being the first to figure out the basic mechanism that generated the history of life, and for writing eloquently and persuasively about it. His big idea was right (even if it took more than 70 years to confirm), but some of his conjectures and mechanisms turned out to be wrong.

He was also, from all accounts, an exceedingly nice man. Among towering intellects and important personalities, that's pretty unusual too.

Labels: anniversary, books, controversy, evolution, science

07 November 2009

The end of the Wall

When I saw the footage of people hammering away at the Berlin Wall 20 years ago, I cried. I've never been there (the closest I came was Frankfurt Airport, three years earlier), but it's where my dad was born in 1939. Berlin has always loomed large in my family's history—through stories from him and my aunt, from my grandmother and step-grandfather, of the War, and the Blockade. And in the phone calls and letters to and from the city, where we still have relatives.

When I saw the footage of people hammering away at the Berlin Wall 20 years ago, I cried. I've never been there (the closest I came was Frankfurt Airport, three years earlier), but it's where my dad was born in 1939. Berlin has always loomed large in my family's history—through stories from him and my aunt, from my grandmother and step-grandfather, of the War, and the Blockade. And in the phone calls and letters to and from the city, where we still have relatives.

Berlin is where my grandfather Karl, my father's father, died in 1947. Thin and weakened in a Russian PoW camp, he returned to his family when the War ended, but never regained his full health. In the ravaged city, medical care wasn't quite good enough, or medicine available enough, to save him when he caught an infection—perhaps pleurisy, perhaps something else. With modern antibiotics and intensive care, he would probably have lived. And I would almost certainly never have been born.

My parents will be in Berlin again this week, able to cross back and forth across the city. The Wall is only shards now, the city and Germany itself now whole, if sometimes awkwardly. I visited Moscow and what was then Leningrad in 1985, while Russia was still fully Communist, though waning. Where today there are billboards, then the signs were only massive revolutionary slogans. To my children, the Cold War is history, long gone before they were born.

But it's not really gone. Current events emerge from what happened then. And my father told me that, a few years ago when he visited the village in the former East Germany to which he'd been evacuated late in the War, the buildings still had bullet holes in the walls.

Labels: anniversary, europe, family, history, war

28 October 2009

Evolution book review: Dawkins's "Greatest Show on Earth," Coyne's "Why Evolution is True," and Shubin's "Your Inner Fish"

Next month, it will be exactly 150 years since Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859. This year also marked what would have been his 200th birthday. Unsurprisingly, there are a lot of new books and movies and TV shows and websites about Darwin and his most important book this year.

Next month, it will be exactly 150 years since Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859. This year also marked what would have been his 200th birthday. Unsurprisingly, there are a lot of new books and movies and TV shows and websites about Darwin and his most important book this year.

Of the books, I've bought and read the three of the highest-profile ones: Neil Shubin's Your Inner Fish (actually published in 2008), Jerry Coyne's Why Evolution is True, and Richard Dawkins's The Greatest Show on Earth: The Evidence for Evolution. They're all written by working (or, in Dawkins's case, officially retired) evolutionary biologists, but are aimed at a general audience, and tell compelling stories of what we know about the history of life on Earth and our part in it. I also re-read my copy of the first edition of the Origin itself, as well as legendary biologist Ernst Mayr's 2002 What Evolution Is, a few months ago.

Why now?

Aside from the Darwin anniversaries, I wanted to read the three new books because a lot has changed in the study of evolution since I finished my own biology degree in 1990. Or, I should say, not much has changed, but we sure know a lot more than we did even 20 years ago. As with any strong scientific idea, evidence continues accumulating to reinforce and refine it. When I graduated, for instance:

- DNA sequencing was rudimentary and horrifically expensive, and the idea of compiling data on an organism's entire genome was pretty much a fantasy. Now it's almost easy, and scientists are able to compare gene sequences to help determine (or confirm) how different groups of plants and animals are related to each other.

- Our understanding of our relationship with chimpanzees and our extinct mutual relatives (including Australopithecus, Paranthropus, Sahelanthropus, Orrorin, Ardipithecus, Kenyanthropus, and other species of Homo in Africa) was far less developed. With more fossils and more analysis, we know that our ancestors walked upright long before their brains got big, and that raises a host of new and interesting questions.

- The first satellite in the Global Positioning System had just been launched, so it was not yet easily possible to monitor continental drift and other evolution-influencing geological activities happening in real time (though of course it was well accepted from other evidence). Now, whether it's measuring how far the crust shifted during earthquakes or watching as San Francisco marches slowly northward, plate tectonics is as real as watching trees grow.

- Dr. Richard Lenski and his team had just begun what would become a decades-long study of bacteria, which eventually (and beautifully) showed the microorganisms evolving new biochemical pathways in a lab over tens of thousands of generations. That's substantial evolution occurring by natural selection, incontrovertibly, before our eyes.

- In Canada, the crash of Atlantic cod stocks and controversies over salmon farming in the Pacific hadn't yet happened, so the delicate balances of marine ecosystems weren't much in the public eye. Now we understand that human pressures can disrupt even apparently inexhaustible ocean resources, while impelling fish and their parasites to evolve new reproductive and growth strategies in response.

- Antibiotic resistance (where bacteria in the wild evolve ways to prevent drugs from being as effective as they used to) was on few people's intellectual radar, since it didn't start to become a serious problem in hospitals and other healthcare environments until the 1990s. As with cod, we humans have unwittingly created selection pressures on other organisms that work to our own detriment.

...and so on. Perhaps most shocking in hindsight, back in 1990 religious fundamentalism of all stripes seemed to be on the wane in many places around the world. By association, creationism and similar world views that ignore or deny that biological evolution even happens seemed less and less important.

Or maybe it just looked that way to me as I stepped out of the halls of UBC's biology buildings. After all, whether studying behavioural ecology, human medicine, cell physiology, or agriculture, no one there could get anything substantial done without knowledge of evolution and natural selection as the foundations of everything else.

Why these books?

The books by Shubin, Coyne, and Dawkins are not only welcome and useful in 2009, they are necessary. Because unlike in other scientific fields—where even people who don't really understand the nature of electrons or fluid dynamics or organic chemistry still accept that electrical appliances work when you turn them on, still fly in planes and ride ferryboats, and still take synthesized medicines to treat diseases or relieve pain—there are many, many people who don't think evolution is true.

No physicians must write books reiterating that, yes, bacteria and viruses are what spread infectious diseases. No physicists have to re-establish to the public that, honestly, electromagnetism is real. No psychiatrists are compelled to prove that, indeed, chemicals interacting with our brain tissues can alter our senses and emotions. No meteorologists need argue that, really, weather patterns are driven by energy from the Sun. Those things seem obvious and established now. We can move on.

But biologists continue to encounter resistance to the idea that differences in how living organisms survive and reproduce are enough to build all of life's complexity—over hundreds of millions of years, without any pre-existing plan or coordinating intelligence. But that's what happened, and we know it as well as we know anything.

If the Bible or the Qu'ran is your only book, I doubt much will change your mind on that. But many of the rest of those who don't accept evolution by natural selection, or who are simply unsure of it, may have been taught poorly about it back in school—or if not, they might have forgotten the elegant simplicity of the concept. Not to mention the huge truckloads of evidence to support evolutionary theory, which is as overwhelming (if not more so) and more immediate than the also-substantial evidence for our theories about gravity, weather forecasting, germs and disease, quantum mechanics, cognitive psychology, or macroeconomics.

Enjoying the human story

So, if these three biologists have taken on the task of explaining why we know evolution happened, and why natural selection is the best mechanism to explain it, how well do they do the job? Very well, but also differently. The titles tell you.

Shubin's Your Inner Fish is the shortest, the most personal, and the most fun. Dawkins's The Greatest Show on Earth is, well, the showiest, the biggest, and the most wide-ranging. And Coyne's Why Evolution is True is the most straightforward and cohesive argument for evolutionary biology as a whole—if you're going to read just one, it's your best choice.

However, of the three, I think I enjoyed Your Inner Fish the most. Author Neil Shubin was one of the lead researchers in the discovery and analysis of Tiktaalik, a fossil "fishapod" found on Ellesmere Island here in Canada in 2004. It is yet another demonstration of the predictive power of evolutionary theory: knowing that there were lobe-finned fossil fish about 380 million years ago, and obviously four-legged land dwelling amphibian-like vertebrates 15 million years later, Shubin and his colleagues proposed that an intermediate form or forms might exist in rocks of intermediate age.

Ellesmere Island is a long way from most places, but it has surface rocks about 375 million years old, so Shubin and his crew spent a bunch of money to travel there. And sure enough, there they found the fossil of Tiktaalik, with its wrists, neck, and lungs like a land animal, and gills and scales like a fish. (Yes, it had both lungs and gills.) Shubin uses that discovery to take a voyage through the history of vertebrate anatomy, showing how gill slits from fish evolved over tens of millions of years into the tiny bones in our inner ear that let us hear and keep us balanced.

Since we're interested in ourselves, he maintains a focus on how our bodies relate to those of our ancestors, including tracing the evolution of our teeth and sense of smell, even the whole plan of our bodies. He discusses why the way sharks were built hundreds of millions of years ago led to human males getting certain types of hernias today. And he explains why, as a fish paleontologist, he was surprisingly qualified to teach an introductory human anatomy dissection course to a bunch of medical students—because knowing about our "inner fish" tells us a lot about why our bodies are this way.

Telling a bigger tale

Richard Dawkins and Jerry Coyne tell much bigger stories. Where Shubin's book is about how we people are related to other creatures past and present, the other two seek to explain how all living things on Earth relate to each other, to describe the mechanism of how they came to the relationships they have now, and, more pointedly, to refute the claims of people who don't think those first two points are true.

Dawkins best expresses the frustration of scientists with evolution-deniers and their inevitable religious motivations, as you would expect from the world's foremost atheist. He begins The Greatest Show on Earth with a comparison. Imagine, he writes, you were a professor of history specializing in the Roman Empire, but you had to spend a good chunk of your time battling the claims of people who said ancient Rome and the Romans didn't even exist. This despite those pesky giant ruins modern Romans have had to build their roads around, and languages such as Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, French, German, and English that are obviously derived from Latin, not to mention the libraries and museums and countrysides full of further evidence.

He also explains, better than anyone I've ever read, why various ways of determining the ages of very old things work. If you've ever wondered how we know when a fossil is 65 million years old, or 500 million years old, or how carbon dating works, or how amazingly well different dating methods (tree ring information, radioactive decay products, sedimentary rock layers) agree with one another, read his chapter 4 and you'll get it.

Alas, while there's a lot of wonderful information in The Greatest Show on Earth, and many fascinating photos and diagrams, Dawkins could have used some stronger editing. The overall volume comes across as scattershot, assembled more like a good essay collection than a well-planned argument. Dawkins often takes needlessly long asides into interesting but peripheral topics, and his tone wanders.

Sometimes his writing cuts precisely, like a scalpel; other times, his breezy footnotes suggest a doddering old Oxford prof (well, that is where he's been teaching for decades!) telling tales of the old days in black school robes. I often found myself thinking, Okay, okay, now let's get on with it.

Truth to be found

On the other hand, Jerry Coyne strikes the right balance and uses the right structure. On his blog and in public appearances, Coyne is (like Dawkins) a staunch opponent of religion's influence on public policy and education, and of those who treat religion as immune to strong criticism. But that position hardly appears in Why Evolution is True at all, because Coyne wisely thinks it has no reason to. The evidence for evolution by natural selection stands on its own.

I wish Dawkins had done what Coyne does—noting what the six basic claims of current evolutionary theory are, and describing why real-world evidence overwhelmingly shows them all to be true. Here they are:

- Evolution: species of organisms change, and have changed, over time.

- Gradualism: those changes generally happen slowly, taking at least tens of thousands of years.

- Speciation: populations of organisms not only change, but split into new species from time to time.

- Common ancestry: all living things have a single common ancestor—we are all related.

- Natural selection: evolution is driven by random variations in organisms that are then filtered non-randomly by how well they reproduce.

- Non-selective mechanisms: natural selection isn't the only way organisms evolve, but it is the most important.

The rest of Coyne's book, in essence, fleshes those claims and the evidence out. That's almost it, and that's all it needs to be. He recounts too why, while Charles Darwin got all six of them essentially right back in 1859, only the first three or four were generally accepted (even by scientists) right away. It took the better part of a century for it to be obvious that he was correct about natural selection too, and even more time to establish our shared common ancestry with all plants, animals, and microorganisms.

Better than other books about evolution I've read, Why Evolution is True reveals the relentless series of tests that Darwinism has been subjected to, and survived, as new discoveries were made in astronomy, geology, physics, physiology, chemistry, and other fields of science. Coyne keeps pointing out that it didn't have to be that way. Darwin was wrong about quite a few things, but he could have been wrong about many more, and many more important ones.

If inheritance didn't turn out to be genetic, or further fossil finds showed an uncoordinated mix of forms over time (modern mammals and trilobites together, for instance), or no mechanism like plate tectonics explained fossil distributions, or various methods of dating disagreed profoundly, or there were no imperfections in organisms to betray their history—well, evolutionary biology could have hit any number of crisis points. But it didn't.

Darwin knew nothing about some of these lines of evidence, but they support his ideas anyway. We have many more new questions now too, but they rest on the fact of evolution, largely the way Darwin figured out that it works.

The questions and the truth

Facts, like life, survive the onslaughts of time. Opponents of evolution by natural selection have always pointed to gaps in our understanding, to the new questions that keep arising, as "flaws." But they are no such thing: gaps in our knowledge tell us where to look next. Conversely, saying that a god or gods, some supernatural agent, must have made life—because we don't yet know exactly how it happened naturally in every detail—is a way of giving up. It says not only that there are things we don't know, but things we can never learn.

Some of us who see the facts of evolution and natural selection, much the way Darwin first described them, prefer not to believe things, but instead to accept them because of supporting scientific evidence. But I do believe something: that the universe is coherent and comprehensible, and that trying to learn more about it is worth doing for its own sake.

In the 150 years since the Origin, people who believed that—who did not want to give up—have been the ones who helped us learn who we, and the other organisms who share our planet, really are. Thousands of researchers across the globe help us learn that, including Dawkins exploring how genes, and ideas, propagate themselves; Coyne peering at Hawaiian fruit flies through microscopes to see how they differ over generations; and Shubin trekking to the Canadian Arctic on the educated guess that a fishapod fossil might lie there.

The writing of all three authors pulses with that kind of enthusiasm—the urge to learn the truth about life on Earth, over more than 3 billion years of its history. We can admit that we will always be somewhat ignorant, and will probably never know everything. Yet we can delight in knowing there will always be more to learn. Such delight, and the fruits of the search so far, are what make these books all good to read during this important anniversary year.

Labels: anniversary, books, controversy, evolution, religion, review, science

21 August 2009

Gnomedex 2009 day 1

My wife Air live blogged the first day's talks here at the 9th annual Gnomedex conference, and you can also watch the live video stream on the website. I posted a bunch of photos. Here are my written impressions.

My wife Air live blogged the first day's talks here at the 9th annual Gnomedex conference, and you can also watch the live video stream on the website. I posted a bunch of photos. Here are my written impressions.

Something feels a little looser, and perhaps a bit more relaxed, about this year's meeting. There's a big turnover in attendees: more new people than usual, more women, and a lot more locals from the Seattle area. More Windows laptops than before, interestingly, and more Nikon cameras with fewer Canons. A sign of tech gadget trends generally? I'm not sure.

As always, the individual presentations roamed all over the map, and some were better than others. For example, Bad Astronomer Dr. Phil Plait's talk about skepticism was fun, but also not anything new for those of us who read his blog. However, it was also great as a perfect precursor to Christine Peterson, who invented the term open source some years ago, but is now focused on life extension, i.e. using various dietary, technological, and other methods to improve health and significantly extend the human lifespan.

- Some stuff Dr. Plait said: "Skepticism is not cynicism." "You ask for the evidence [...] and make sure it's good." "Be willing to drop an idea if it's wrong. Yeah, that's tough." "Scientists screw it up as well." "It sucks to be fooled. You can lose your money. You can lose your life."

- Christine Peterson: "Moving is how you tell your body, I'm not dead yet!" "You see people hitting soccer balls with their heads. Would you do that with your laptop? And that's backed up!" (You might like my friend Bill's reaction on my Facebook page.)

As Lee LeFever quipped on Twitter, "The life extension talk is a great followup to the skepticism talk because it provides so many ideas of which to be skeptical." My thought was, her talk seemed like hard reductionist nerdery focused somewhere it may not apply very well. My perspective may be different because I have cancer; for me, life extension is just living, you know? But I also feel that not everything is an engineering problem.

There were a number of those dichotomies through the day. Some other notes I took today:

- Bre Pettis passed out 3D models "printouts" created with the MakerBot he helped design. "Bonus points for being able to print out your... uh... body... parts." "Oh my god, you should put this brain inside Walt Disney's head!" "What's black ABS plastic good for?" "Printing evil stuff."

- One of the most joyous things you'll ever see is a keen scientist really going off on his or her topic of specialty. Firas Khatib on FoldIt protein folding was one of those. For a given sequence of amino acids, the 3D protein structure with lowest free energy is likely to be its useful shape in biology—and his team made a video game to help people figure out optimum shapes, which in the long run can help cure diseases.

- Todd Friesen is a former search engine and website spammer. He had lots of interesting things today. In the world of white and black search engine optimization (SEO), SPAM = "Sites Positioned Above Mine." For spammers, RSS = "Really Simple Stealing" and thus spam blogs. Major techniques for web spammers: hacking pages, bribing people for access, forum posts and user profiles, comment spam. Pay Per Click = PPC = "Pills, Porn, and Casinos."

- I liked these from the Ignite super-fast presentations: "There are more social media non-gurus than social media gurus. Which means we can take them." On annual reports: "Imagine waiting A YEAR to find out what a company is doing."

We had a great trip down to Seattle via Chuckanut Drive with kk+ and Fierce Kitty. Tonight Air and I are sleeping in the Edgewater Hotel on Seattle's Pier 67, next to the conference venue, and tonight is also the 45th anniversary of the day the Beatles stayed in this same hotel and fished out the window.

Labels: anniversary, band, biology, conferences, geekery, gnomedex, history, music, science, travel

19 August 2009

Proud to be her man

As of today, August 19, 2009, my wife Air and I have been married 14 years. As on our wedding day, the weather was Amazing Vancouver Summer last evening, our Anniversary Eve: mid-20s Celsius, sun glinting off the water. The kind of weather which impels people to spend thousands of dollars to visit. We went to C Restaurant on False Creek, where we'd last dined exactly three years ago, just before our 11th anniversary.

As of today, August 19, 2009, my wife Air and I have been married 14 years. As on our wedding day, the weather was Amazing Vancouver Summer last evening, our Anniversary Eve: mid-20s Celsius, sun glinting off the water. The kind of weather which impels people to spend thousands of dollars to visit. We went to C Restaurant on False Creek, where we'd last dined exactly three years ago, just before our 11th anniversary.

You know that "in sickness and in health" thing? Don't take it lightly—we've had more than our share of that seesaw over the past decade and a half. Even yesterday, it was touch-and-go whether we'd have to cancel our reservation.

You see, I was tuckered out after moving some of the kids' furniture all afternoon, and feared the onset of the dreaded chemo-induced Jurassic Gut. But with the help of some medicine, the prospect of an excellent and relaxing meal, the sheer fabulousness of looking at my wife, and a lot of willpower and positive thinking, I not only made it downtown, but was symptom-free throughout dinner and the whole trip home. (And then everything got rolling once we returned, but I won't give you details...)

The restaurant provided some little extras for us: custom chocolate script on our dessert plate, plus post-dinner ice wine on the house. We spent a leisurely two and a half hours eating wonderful, creative seafood, and we held hands to look out across the water, making occasional snarky comments about passersby on both land and sea. When we told the waiter we were celebrating 14 years, he asked, "Did get married when you were teenagers?" That's a nice compliment, since we were both 26 back then.

Air and I have been happy and sad, content and afraid together. I'm not as strong or healthy as I used to be, and I'm greyer and far more scarred and broken. But I am proud to be her man, and I'll do my damnedest to be here for as many more anniversaries as I can.

Labels: anniversary, cancer, chemotherapy, food, love, oceans, restaurant

24 July 2009

Splashdown

Today we mark 40 years since the Apollo 11 Command Module Columbia splashed down in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, a few hundred kilometres from the now-closed Johnston Island naval base:

Our first (and sixth last!) trip to the surface of the Moon was over. The seared, beaten Columbia (weighing less than 6,000 kg, and which had remained shiny and pristine until its re-entry into the Earth's atmosphere), with its passengers, was the only part of the titanic Saturn V rocket (3 million kg) to return home after a little over one week away. Every other component had been designed to burn up during launch or return, to stay on the Moon's surface (where those parts remain), to smash into the Moon, or to drift in its own orbit around the Sun.

All three astronauts returned safely, and suffered no ill effects, despite being quarantined for two and a half weeks, until August 10, 1969, when I was six weeks old.

Labels: anniversary, astronomy, holiday, moon, oceans, science, space

21 July 2009

Going home

Just before noon today, Pacific Time, marks exactly 40 years since Neil armstrong and Buzz Aldrin launched their Lunar Module Eagle and left the surface of the Moon, to rendezvous with their colleague Michael Collins in lunar orbit:

They were on their way home to Earth, though it would take a few days to get back here.

Labels: anniversary, astronomy, holiday, moon, science, space

20 July 2009

Today was the day

The beginnings of human calendars are arbitrary. We're using a Christian one right now, though the start date is probably wrong, and the monks who created it didn't assign a Year Zero. Chinese, Mayan, Hindu, Jewish, Muslim, and other calendars begin on different dates.

If we were to decide to start over with a new Year Zero, I think the choice would be easy. The dividing line would be 40 years ago today, what we call July 16, 1969. That's when the first humans—the first creatures from Earth of any kind, since life began here a few billion years ago—walked on another world, our own Moon:

They landed their vehicle, the ungainly Eagle, at 1:17 p.m. Pacific Daylight Time (the time of my post here). Just before 8 PDT, Neil Armstrong put his boot on the soil. That was the moment. All three of the men who went there, Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins, are almost 80 now, but they are still alive, like the rest of the relatively small slice of humanity that was here when it happened (I was three weeks old).

If the sky is clear tonight, look up carefully for the Moon: it's just a sliver right now. Although it's our closest neighbour in space, you can cover it up with your thumb. People have been there, and when the Apollo astronauts walked on its dust, they could look up and cover the Earth with a gesture too—the place where everyone except themselves had ever lived and died. Every other achievement, every great undertaking, every pointless war—all fought over something that could be blotted out with a thumb.

Even if it doesn't start a new calendar (not yet), today should at least be a holiday, to commemorate the event, the most amazing and important thing we've ever done. Make it one yourself, and remember. Today was the day.

Labels: anniversary, astronomy, holiday, moon, science, space

16 July 2009

Launch day

Forty years ago today. July 16, 1969, 9:32 a.m. EDT, Launch Complex 39A, Cape Canaveral, Florida. Three nearly hairless apes—human beings in pressure suits—left for the Moon:

They were aboard the world's greatest machine, which put out about 175 million horsepower during launch. Less than three hours later, they exited Earth orbit and were on their way.

Labels: anniversary, astronomy, moon, science, space

18 May 2009

Boom

On the morning of May 18, 1980, exactly 29 years ago, I was camping with my Boy Scout troop at Furry Creek, north of Vancouver on the shore of Howe Sound. (The location is now part of a large golf course development, but at the time was essentially just forest near the highway.)

On the morning of May 18, 1980, exactly 29 years ago, I was camping with my Boy Scout troop at Furry Creek, north of Vancouver on the shore of Howe Sound. (The location is now part of a large golf course development, but at the time was essentially just forest near the highway.)

We awoke, terrified, to an enormous thundering crash. It was not, as we had thought, a train derailment on the railroad right near our campsite. It was the titanic sound of the eruption of Mount St. Helens—a sound which had arrived after traveling about 300 km northwest from the explosion. Back in Vancouver, my dad thought our water heater had exploded in the basement.

It was a good reminder that we live in a zone of earthquakes and volcanoes.

Labels: americas, anniversary, history, volcanoes

17 April 2009

Cannon Beach days

My wife, kids, and I have spent quite a bit of time in Cannon Beach, Oregon, where we took our summer vacations several years in a row. We like the place: it's in the United States, another country, yet it's part of the same sort of coastal ecosystem as we have here in British Columbia. So it's familiar, yet foreign, and one of my favourite places.

My wife, kids, and I have spent quite a bit of time in Cannon Beach, Oregon, where we took our summer vacations several years in a row. We like the place: it's in the United States, another country, yet it's part of the same sort of coastal ecosystem as we have here in British Columbia. So it's familiar, yet foreign, and one of my favourite places.

Today my parents, who are returning from a road trip to San Diego, have happened into staying a night in Cannon Beach too. They phoned me tonight as they had a light dinner and wine on the patio of their motel, watching the sunset. Today is also their 44th anniversary. They like the place too.

Incidentally, after they checked in, my mother realized that, decades ago, she had stayed at the same motel with her longtime friend Erlyne.

Labels: americas, anniversary, cannonbeach, family, holiday, travel

04 April 2009

20 years behind the kit

Twenty years ago this spring, I played my first gig as a drummer, at the Last Class Bash for the UBC Science Undergraduate Society. Our band, the Juan Valdez Memorial R&B Ensemble, was a five-piece with me on drums, my roommates Alistair, Sebastien, and Andrew on guitars and bass, and Ken Otter (now a professor of zoology) on another guitar.

Twenty years ago this spring, I played my first gig as a drummer, at the Last Class Bash for the UBC Science Undergraduate Society. Our band, the Juan Valdez Memorial R&B Ensemble, was a five-piece with me on drums, my roommates Alistair, Sebastien, and Andrew on guitars and bass, and Ken Otter (now a professor of zoology) on another guitar.

We'd spent months rehearsing, but we still didn't know how to sing proper harmonies. Our playlist included mostly old songs from the '60s: "Gloria," "Long Cool Woman," the theme from "Batman." I skipped a final lecture for one of my high-level biology courses to set up for the show in the Student Union Building party room. Our friend Steve ran the rented PA system.

We were relatively terrible, but we were silly, and we had a good time. So did the heavy-drinking audience.

I'm still playing in a later version of the same band. Sebastien is still on guitar, I'm still on drums when I feel up to it. We're still playing some of those same songs. I've spent half my life in this act.

Labels: anniversary, band, friends, memories, music, neurotics, school

12 February 2009

Darwin day

Charles Darwin was born 200 years ago today, and has been dead for almost 127 years. That's a long time in human terms, but no time at all in the history of life on earth. Though the true age of our planet (about 4.6 billion years) wasn't yet clear in his time, Darwin knew that it was very old—old enough to have changed a whole lot, and for life to have evolved along with it.

Charles Darwin was born 200 years ago today, and has been dead for almost 127 years. That's a long time in human terms, but no time at all in the history of life on earth. Though the true age of our planet (about 4.6 billion years) wasn't yet clear in his time, Darwin knew that it was very old—old enough to have changed a whole lot, and for life to have evolved along with it.

If he hadn't, someone else would have figured out around Darwin's time that evolution happens by natural selection. The evidence, from geology, paleontology, island ecology, animal breeding, and other fields was there. Indeed, someone else did figure it out, and when Alfred Wallace wrote to Darwin about "the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely From the Original Type" in 1857, he spurred Darwin to spend two years compiling his own ideas on the subject (by then 20 years old), in On the Origin of Species, 150 years ago this year.

The discovery

But while the idea of natural selection was ripe for discovery in the mid-1850s, Charles Darwin was uniquely suited to refine and present it. He was a polymath, interested in a huge variety of subjects. He was a well-respected member of the British social and scientific establishment, so his ideas would be heard. He had traveled the world, observing and collecting different species of animals and plants, before returning to England to become a settled homebody, set on performing exacting experiments to tease out the subtleties of biological phenomena.

Long before he wrote the Origin, he understood the implications of his discovery, especially to Biblical interpretations of creation—he had trained for the ministry in his youth, and his wife Emma was very religious—so he knew that he would have to assemble all the overwhelming evidence he had, and argue it well, to make his case. That's one reason he waited 20 years.

Despite knowing nothing of genetics, plate tectonics, or modern developmental biology, and having few transitional fossil finds to refer to, Darwin and Wallace were fundamentally correct in their discovery:

- Individual animals, plants, fungi, and unicellular organisms produce more offspring than can survive and successfully reproduce themselves.

- Those offspring vary in numerous characteristics, some of which offer survival and reproductive advantages in their current environment.

- Offspring with variations that offer advantages produce more offspring than their siblings with variations that don't.

- Over time, those individuals with the advantageous variations come to dominate populations.

- Different populations of a single species exist in different environments, and environments also change, so the variations that work best will probably differ between populations and over time. Eventually, those variations compound, and the populations may diverge or evolve into new species.

The mystery

So while many people assume that On the Origin of Species addresses how life originated on earth to start with, it doesn't—that remains a mystery biologists are still trying to solve 150 years later. Darwin himself suggested that life was "originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one."

His book solved another mystery altogether: how new species originate from existing ones. In doing so, Charles Darwin effectively created the science of biology, drawing the study of living things into a cohesive subject, where insights in one field (such as the chemical structure of deoxyribonucleic acid inside cells) could relate to others (like the geographic distribution of animals, or even human medicine).

The argument

Darwin was a shy, sensitive family man averse to controversy, but he was also stubborn, logical, meticulous, and a completist. The Origin is over 300 pages, but he wrote it as a mere abstract of the comprehensive book he really wanted to write (and never did). Even in its "abbreviated" form, it is a progressing, relentless treatise, building fact upon fact.

He doesn't introduce the concept of natural selection until the fourth chapter (of 15 total). He builds a foundation, introduces his discovery, marshals evidence, raises objections, and addresses them. He talks about instinct, breeding, geology, geography, morphology, and embryology. Then, just to be sure you've got it, he writes a final chapter summarizing everything—all in long Victorian paragraphs.

Honestly, On the Origin of Species is a pretty dull read. But it is a stupendous argument.

The evidence

The test of a scientific theory is not only what it explains, but what it predicts—even beyond what its formulators might have imagined. We know Newton's laws of motion are right because we use them to send men to the moon and probes to planets, and to predict eclipses. We know Einstein was right because lasers actually work, and because gravity really does bend light, whether as close by as the sun or as far away as the most distant galaxies. We know continental drift is real for a bunch of reasons, but today we can even use precise satellite measurements to watch it happening in real time.

Countless theories are obsolete because their predictions don't pan out: a young and earth-centred universe under an unchanging dome of stars, four elements (earth, air, fire, water), aether and phlogiston, Lamarckian inheritance, magical alchemy (Isaac Newton was convinced about that one), spontaneous generation, health as a balance of humours, absolute time, the indivisible atom, Darwin's own ideas about the mechanisms of inheritance, and on and on.

We refine other theories based on new evidence, because their predictions are close, but not quite right. Today, for newer theories, we build huge machines just to find out whose predictions match with reality.

What amazes us about Darwin, and Newton, and Einstein (and others)—what shows us that they were right—is that new evidence keeps turning up, and either refines or confirms what their most important theories predict, but doesn't refute it. Newton's theories work so well we hardly think about them: we just buy cameras with refracting lenses, fly in planes with jet engines, drive cars with airbags, or turn on our GPS units, and we expect them to work. Einstein showed some extreme situations where Newton's laws don't properly apply, and we learned from that how to make laser pointers, take radiation therapy, and fear nuclear weapons.

The predictions

Evolution by natural selection, as Darwin and Wallace figured it out, suggested that we would find many other things, such as:

- Many more transitional fossil forms—yes, and more all the time.

- Mechanisms for inheritance of variation—those are genes and DNA.

- Ways for geographically distant but related organisms to have once shared ancestors—continental drift and deep time are two big ones there.

We have found those things, in spades. But the evidence goes far further, including:

- Animals and plants that Darwin surmised must be related because of their appearance and habits also share more DNA than those less closely related—something he could never have known, but that provides two independent lines of evidence to the same conclusion.

- Evolution is usually slow, but in organisms that live and reproduce fast, like the AIDS virus adapting against our drugs, E. coli tolerating poisons in the lab, or antibiotic-resistant bacteria spreading in hospitals, we can see it happen over mere decades.

- Using biotechnology, we can synthesize new species ourselves—such as by corralling bacteria to make human insulin or to devour oil spills—but only when we apply the genetic mechanisms that we have discovered allow natural selection and drive evolution.

From biochemistry and molecular biology to evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo), gene therapy, and evolutionary psychology, whole fields of study depend on the principles of natural selection. Without them, those fields could not make their own predictions or solve problems in the real world.

Yet here's the thing: they do.

The day

That's why today, Darwin day, is worth commemorating. Charles Darwin figured out the basis for how life works 150 years ago. He explained it, and no matter how controversial it remains, natural selection is the basis for how we understand the family of all organisms, extinct or living, which includes ourselves, over several billion years.

He was a proper Victorian country gentleman, so I doubt anyone ever called him "Chuck." But he's 127 years dead now, so he has no reason to mind my saying this: Happy birthday, Chuck. And thanks.

Labels: anniversary, birthday, controversy, evolution, science

20 November 2008

Berlin 1965

For as long as I can remember, my parents have had this photo hanging on their bedroom wall:

I made a copy last night because my younger daughter has a project at school where she's discussing Germany, and she wanted a copy of this picture to illustrate Berlin, where it was taken. It was 1965, on my parents' honeymoon. My mom and dad were 26 at the time, and that's the city's mascot, a bear, between them. Here they are today (without the bear):

My dad still wears collared shirts most of the time, though my mom isn't into the bonnets anymore.

They look young in that first photo. My wife and I were the same age, 26, when we got married 30 years later. We didn't feel so young then, but we were too.

Labels: anniversary, europe, family, photography, school

15 November 2008

The Lions' Gate and Pattullo turn 70

According to Tod Maffin and Buzz Bishop, this week marks the 70th birthdays of both the Lions' Gate Bridge and the Pattullo Bridge here in Greater Vancouver. It would be hard for two bridges to contrast more in their appearance:

The Lions' Gate (connecting downtown Vancouver's Stanley Park with the North Shore across Burrard Inlet) is an elegant suspension bridge, lit at night with glittering lamps, and a beautiful landmark admired throughout the city and the world. It's on many of the city's postcards. It was heavily refurbished a few years ago, but looks the same as it always has.

The Pattullo (connecting New Wesminster to Surrey) is an ungainly girdered structure often cursed by those who must drive its narrow, dangerous lanes. Premier Duff Pattullo, after whom it is named, apparently called it "a thing of beauty." Tod says, "Yes, he was likely stoned." Plans are afoot to knock it down and replace it.

Labels: anniversary, architecture, birthday, design, vancouver

27 October 2008

Happy eighth birthday, blog

Today marks eight years since this site first became a blog, back on October 27, 2000. That's the day I started using Blogger—long before Google bought it—to publish updates here, instead of doing them manually in a text editor. (I did so on the recommendation of my friend Alistair—who was also standing next to me in the photo I cropped down as my portrait at the time.) Believe it or not, I'm still using Blogger to run the site, although I don't host it on Blogger's servers, and I make my own templates.

Today marks eight years since this site first became a blog, back on October 27, 2000. That's the day I started using Blogger—long before Google bought it—to publish updates here, instead of doing them manually in a text editor. (I did so on the recommendation of my friend Alistair—who was also standing next to me in the photo I cropped down as my portrait at the time.) Believe it or not, I'm still using Blogger to run the site, although I don't host it on Blogger's servers, and I make my own templates.

That day back in 2000 was also a little over seven months after I first registered the penmachine.com domain—in the three years before that, I'd been publishing at various obscure URLs owned by my ISP and others. However, the alias www.pobox.com/~dkmiller will still get you here, as it always has. So, courtesy of the Wayback Machine, here are some looks back:

- Take a look at this site in September 2000, before I blogified it. I also have a screenshot of an even earlier version, plus a preserved HTML archive from 1998.

- You can also examine roughly how it looked in 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, and 2008. You know, this blog hasn't changed as much as I might have thought.

- As far as I can tell, the most popular thing I've ever written here is my 2005 article about buying a cheap guitar, which remains my most-viewed page more than three years after I published it, and more than two years after I last made any updates to it. If you post stuff on the web, that shows you why you should avoid breaking links.

- To reinforce that, this month 30 people took at look at my earliest blog archive, and 140 people (!) read my spelling article, which was pretty much the first thing I ever published on the Web, back in 1997. Earlier this year, an editor colleague of mine finally spotted a typo in the piece—even though it had been online and widely read for 11 years. So I fixed it.

- In the past eight years, I'm not sure if I've had visitors from every country in the world, but I have had at least one each (and probably more, given that many people's browsers don't reveal their location) from Namibia, Greenland, Tajikistan, Vanuatu, and Nicaragua, among others.

- My biggest traffic spikes have come via Jason Kottke and John Gruber, which is little surprise if you know their sites.

Given how things are going, I have no idea whether I'll still be writing here in another eight years. But it's been fun so far.

Labels: anniversary, birthday, blog, friends, linkbait, web

11 September 2008

Chemo is suddenly over again, for now

So, how do I put this? The chemotherapy isn't working (at least, not well enough), so my doctors have cancelled it and we're looking for something else to keep the cancer from progressing. That may include different, more experimental forms of chemo, or surgical radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of the spots in my lungs. In my initial reading, the RFA approach looks like it could be promising.

My emotions about this development are all over the place. To know that the largest metastatic lesion in my lungs has grown from 1.4 cm to 1.6 cm in diameter, and the smaller one from 1 cm to 1.4 cm, is dismaying, because the panitumumab and irinotecan I was taking weren't doing the job of stopping or shrinking those tumours. On the other hand, I may have been misinformed about there being four metastases; there might be only two. I'm not sure and will have to ask. They are small, and not growing extremely fast.

In addition to that, now I can avoid spending two days in bed every two weeks, feeling like I'm going to throw up. My pervasive dry skin and facial rash, although under control, should now abate as the chemo drugs flush out of my system. Finally, since it will take a few weeks to figure out and schedule my next treatments, whatever they are, I'm taking the chance to try to have my ileostomy surgically reversed, so that my intestines function normally again for the first time in well over a year and I can ditch the colostomy bags forever. That could happen in less than a month.

We found all this out a couple of days ago, which happened to be my wife Air's 40th birthday. Fortunately, we'd already had a big family-and-friends barbecue last weekend to celebrate that (plus my mom's upcoming 70th), so the news only dampered the day itself, not the party. Last night she and I went for dinner at the beautiful Horizons restaurant here in Burnaby, to mark her birthday and to celebrate at least the end of chemo, for now.

This all reminds me that while my medical team and I keep looking for a cure, something to destroy the cancer completely, more likely we're just buying me time. How much time, no one knows. Months? Years? Right now, other than the dry skin, I feel better than I have at any time since my diagnosis in January 2007. I feel less like a dead man walking than ever, but the future remains a mystery.

Yet on September 11, another dreadful anniversary, the weather here in Vancouver is once again beautiful, and there's laundry to be done. Time to load up the iPod and get to it.

Labels: anniversary, birthday, cancer, chemotherapy, death, pain, surgery

06 September 2008

Two looks ten years back

It's weird to think that my website here is older than Google.

And valued a tad less on the markets, too.

Labels: anniversary, birthday, blog, google, web

04 September 2008

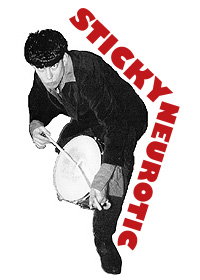

Up to ten thousand

It's not exactly a brilliant piece of photographic art, but it is pretty funny: this is the 10,000th picture taken with my Nikon D50 digital camera since I got it pretty much exactly two years ago. I didn't even take the photo, which is of "Bongo Neurotic," who was playing percussion with us yesterday; guitar player Sean borrowed my camera to snap it.

It's not exactly a brilliant piece of photographic art, but it is pretty funny: this is the 10,000th picture taken with my Nikon D50 digital camera since I got it pretty much exactly two years ago. I didn't even take the photo, which is of "Bongo Neurotic," who was playing percussion with us yesterday; guitar player Sean borrowed my camera to snap it.

To reach 10,000 photos in two years is around 13.7 photos per day, on average, every day. Every. Single. Day. So while I like my film camera too, I'm glad I haven't had to pay for a roll of film (plus processing and printing) every day or two during that time.

Interestingly, the shutters on modern DSLR cameras are often tested for 100,000 or 150,000 or even 300,000 actuations—at my current rate, I'd have to keep going for between 10 and 30 years before the shutter wears out. I expect I'll probably replace the camera a few times in that span, assuming I even live that long.

Labels: anniversary, band, nikon, photography

22 August 2008

Happy birthday, IHR

The podcast I co-host, Inside Home Recording, turned three years old today. That's pretty old for a podcast.

Labels: anniversary, audio, birthday, insidehomerecording, podcast

19 August 2008

Lucky thirteen

Thirteen years ago today, I was nervous and didn't sleep well. I had a garment bag hanging in the closet, and a couple of my best friends were staying with me. But my girlfriend Air, whom I lived with, wasn't there.

Thirteen years ago today, I was nervous and didn't sleep well. I had a garment bag hanging in the closet, and a couple of my best friends were staying with me. But my girlfriend Air, whom I lived with, wasn't there.

That's because we were getting married later that morning. She had stayed overnight with her two close friends, her wedding attendants. In the morning I put on my tuxedo and made my way to the Hart House on Deer Lake, not far from our home.

I didn't see Air arrive in the rented vintage Bentley limo with her friends and family. I waited outside on the lakeside lawn of the old mansion-turned-restaurant, under the huge tree at the end of the red carpet, with our 75 guests. I finally saw her emerge from the building into the sun as we played Van Morrison's "Crazy Love" on a boom box.

We've been together ever since, through thick and thin. And thick and thin there has been. I don't know who I'd be without her. Nor would I want to know.

Labels: anniversary, family, love, memories

30 June 2008

Rock from on high

One hundred years ago today, St. Petersburg, Russia, would have been annihilated by an enormous explosion—if the detonation had occurred less than five hours later than it actually did. But as it turned out, the event happened thousands of kilometres further east, smack dab in the middle of Siberia. St. Petersburg was lucky, saved by the rotation of the earth.

The fireball now known as the Tunguska Event was the mid-air explosion of an extraterrestrial object of some sort (link via PZ Myers), likely a meteorite or fragment of a comet—fairly big, perhaps 50 or 60 metres in diameter, like a condominium tower falling from the sky at several thousand kilometres per hour—which disintegrated violently in the atmosphere. The place is still a remote Siberian forest, several hundred kilometres northwest of Lake Baikal. Trees that fell then still lie on the ground a century later. The heat created microscopic glass beads in the soil. There would be no airburst of similar magnitude until the invention of the hydrogen bomb.

It took almost 20 years for a Soviet scientific expedition, led by Leonid Kulik, to visit the area and survey the still-extensive damage in 1927: while there was no obvious crater, trees had been stripped of their branches and bark, as well as flattened by the shock wave, in a region some 50 km wide. Had the Tunguska Event occurred in a populated area, tens or hundreds of thousands of people might have died.

It was nothing, of course, compared to other impact events on earth, such as those linked with mass extinctions in the more distant past. But I still wouldn't have wanted to be anywhere near it.

Incidentally, Tunguska shares its centenary not only with my 39th birthday today, but also with something else I'd probably prefer to steer clear of: the 45th birthday of Yngwie Malmsteen.

Labels: anniversary, astronomy, birthday, disaster, guitar, history

22 April 2008

Burnaby's birds, beavers, bogs, and boats

The city of Burnaby, B.C., where I grew up and live, is just to the east of Vancouver itself, and is well known for a significant amount of parks and other green space for such an urban environment. One part of that is Burnaby Lake, a fairly large and extremely shallow wetland in the centre of the municipality.

The city of Burnaby, B.C., where I grew up and live, is just to the east of Vancouver itself, and is well known for a significant amount of parks and other green space for such an urban environment. One part of that is Burnaby Lake, a fairly large and extremely shallow wetland in the centre of the municipality.

The lake sits in Burnaby's central valley, and forms part of a waterway that starts at Trout Lake in Vancouver, runs east along Still Creek through Burnaby into the lake, and out into the Brunette River, which flows east and then south through Coquitlam into the Fraser River, which empties westward into the ocean. In recent decades governments have dredged the lake several times, both to provide enough depth for competitive rowing and to avoid having excessive sediment from development and the city's storm sewer system turn the lake into a mudflat—which is why the water's edge is so sharp in the satellite photo.

My wife had the great idea of taking the kids on a ten-minute car ride down the hill from our house every few days to check out the waterfowl and other birds, and to see if any chicks have arrived yet this spring. So far they haven't. But there are tons of animals and plants there, from birds such as ducks, Canada geese, crows, and pigeons to carp, frogs, squirrels, and even a significant population of beavers, the world's largest rodent and Canada's mascot.

My wife had the great idea of taking the kids on a ten-minute car ride down the hill from our house every few days to check out the waterfowl and other birds, and to see if any chicks have arrived yet this spring. So far they haven't. But there are tons of animals and plants there, from birds such as ducks, Canada geese, crows, and pigeons to carp, frogs, squirrels, and even a significant population of beavers, the world's largest rodent and Canada's mascot.

She's gone down there with them a bunch of times, but this weekend I was feeling well enough to tag along. And a couple of days ago the sunny weather and abundant animals brought out another example of local wildlife: the Canadian wildlife photographer, whose distinctive plumage and plaintive ktsch-ktsch-ktsch-ktch call (known affectionately as the "shutter-and-mirror-slap") were in fine form down at the Piper Spit pier. The next day we visited again (this time one of the girls' school friends joined us), but our bunch was alone because of the cold and rain, which actually turned to snow briefly.

The entrance to that part of the park also crosses some railway tracks, which our daughters enjoy putting pennies on to see if they'll be flattened by passing trains. We're accumulating quite a collection of thin copper ovals now.

The entrance to that part of the park also crosses some railway tracks, which our daughters enjoy putting pennies on to see if they'll be flattened by passing trains. We're accumulating quite a collection of thin copper ovals now.

Exactly 20 years ago, in April 1988, I was working a summer job as a park naturalist, headquartered at the nature house at this exact spot, between the railway and the boardwalk. That job was where my wife and I first met. We led canoe tours of the lake some evenings (no motor craft allowed), and this year we're thinking of getting a canoe and taking our kids out there too.

Labels: anniversary, environment, family, friends, love, memories, park, vancouver

08 April 2008

Whole lotta lip gloss

I didn't really get podcasting at all until the middle of 2005, which was some months after the technology first appeared in late 2004—and right about the time iTunes started supporting it. The first person to start a real podcast in our family was my wife, who launched Lip Gloss and Laptops with her friend KA in March 2006.

I didn't really get podcasting at all until the middle of 2005, which was some months after the technology first appeared in late 2004—and right about the time iTunes started supporting it. The first person to start a real podcast in our family was my wife, who launched Lip Gloss and Laptops with her friend KA in March 2006.

Their show has now reached its 100th episode. That would be a milestone in any medium, but in podcasting it's a big one. A good percentage of podcasts podfade and stop publishing long before their 100th show. Others, like my my personal podcast and the other one I co-host, publish irregularly and so take a long time to rack up the numbers (despite starting back in 2005, Inside Home Recording hasn't even reached episode 60 yet).

But other than a few holidays over Christmas and such, Lip Gloss and Laptops has come out every Wednesday for over two years. Even if you're not into the beauty and cosmetics industry, which it covers, it's an interesting and informative listen. (As the show's audio engineer, I hear every episode.)

So congratulations to Airdrie and Kerry Anne on their 100th show. I'm sure they'll be hearing lots more cheers from their fans around the world too.

Labels: anniversary, family, lipglossandlaptops, podcast

14 February 2008

Ten and twenty

The stereotype is that children seem to grow up instantly, but that's not my experience. Our older daughter turned ten today, Valentine's Day. She was born the same day that Catriona Le May Doan won a gold medal at the 1998 Nagano Winter Olympics. Coincidentally, a couple of our good friends had their first child, also a daughter, two days ago. It occurred to me that by the time this new little girl reaches ten, my daughter will be twenty—the age I graduated from university.

The stereotype is that children seem to grow up instantly, but that's not my experience. Our older daughter turned ten today, Valentine's Day. She was born the same day that Catriona Le May Doan won a gold medal at the 1998 Nagano Winter Olympics. Coincidentally, a couple of our good friends had their first child, also a daughter, two days ago. It occurred to me that by the time this new little girl reaches ten, my daughter will be twenty—the age I graduated from university.

The past ten years haven't, as the saying usually goes, gone by in a flash. They feel like ten years, really. And that's great. When my wife and I each held our friends' newborn yesterday, in the same hospital where our daughters (and I) were born, the little one's tiny sleeping face and delicious infant smell took us back to those early days when we first dove head-first into the sleep deprivation of early parenthood.

Since then we've had another daughter, now eight, and the kids have grown, learned to walk and talk and read and write and ride bikes and play piano, gone to preschool, made friends, started kindergarten, and now are in the second and fourth grades. They're learning math and spelling and have their own blogs and Gmail accounts. It doesn't surprise me that it took a decade to get here.

This spring also marks the twentieth anniversary of the day my wife and I first met, when we both worked as park naturalists for the Greater Vancouver Regional District parks department (now called Metro Vancouver Regional Parks). We were friends for a few years after that at the University of B.C., then lost touch until spring 1994, when we met again and started dating. By our first Valentine's Day, in 1995, we were already sharing a house and planning our wedding, which took place that August:

She's been my wonderful Valentine ever since, and I've never wanted another. Twenty years doesn't seem an unreasonable time since then either. We've shared and endured a lot together.

Simply being able to say "I met my wife twenty years ago" does make me feel a bit old, but I like that too. Grey hairs might or might not be a sign of wisdom, but they are a sign that I'm still alive. So 2008 is an important anniversary year, especially following the last one. Happy birthday to my daughter. Happy Valentine's Day to my wife. Happy one more day for me.

Labels: age, anniversary, birthday, family, love

08 January 2008

A year of sometimes salty language

Today's the one year anniversary of the day I first heard my cancer diagnosis. Back then I thought that, even though it was cancer, it was likely early stage and relatively easy to treat.

That was wrong, as I discovered quickly. While today marks one year since my diagnosis, I started counting my treatment last January 31, which means I'm at something like Day 341 now, and far from completing even this round of chemo and other drugs. Whew. I thought I might be away from work for two months—it's now been eleven.

Still, the news has recently been encouraging, since my metastatic lung tumours seem to be responding reasonably to my current chemotherapy. My doctors and my efforts to look at my cancer both optimistically and pragmatically, as well as amazing support from my wife and kids and others in my life, have kept me alive for a year.

Even though I've received gifts of lots of very fine scotch whisky this year, right now I can't drink any alcohol without feeling like crap, so that stuff will have to keep.

Labels: anniversary, cancer, chemotherapy, ego, surgery

31 October 2007

Happy blogiversary

Darn, I missed it again. Saturday, October 27 was this website's seventh birthday as a blog—it existed for three years and a bit before that as a set of plain old "web pages," but not with regular updates. I've been using Blogger to run it ever since that switch. (If I were starting today, I'd probably go with WordPress, but there's a lot of momentum.)

So happy blogiversary this week, Penmachine. I haven't tried a word count in a long time, but I'd bet it's scary. I'm up to 2,927 individual posts, so this blog is probably north of 800,000 words by now.

Labels: anniversary, birthday, geekery, web

10 October 2007

Wacka wacka!

Your friend and mine, Pac-Man turns 28 years old today.

Your friend and mine, Pac-Man turns 28 years old today.

I never had a full-fledged case of Pac-Man Fever, but I did spend a good amount of time playing clones like Gobbler, Snack Attack, and Taxman on my Apple II. Plus I had the September 1982 Mad magazine with Pac-Man on the cover.

The Nintendo version is now available as a cheap download or disc for our Wii, or even for my iPod—maybe I should give it a spin for nostalgia's sake.

Labels: anniversary, apple, birthday, games, geekery, history, nintendo

04 October 2007

Happy birthday, Sputnik

Back in the late 1970s, a traveling exhibition of Soviet space program artifacts and replicas came to the H.R. MacMillan Planetarium here in Vancouver. My parents had bought a lifetime membership to the Planetarium when it opened in the late '60s, so we went there all the time, and this was a particularly exciting event.

Back in the late 1970s, a traveling exhibition of Soviet space program artifacts and replicas came to the H.R. MacMillan Planetarium here in Vancouver. My parents had bought a lifetime membership to the Planetarium when it opened in the late '60s, so we went there all the time, and this was a particularly exciting event.

The part that made the biggest impression on me was the very loud demonstration scale model of the massive Soyuz rocket that launched (and still launches) Russian space capsules. I remember its distinctly Russian shape, with the flared boosters at the bottom, so different from the straight-arrow American designs such as the Saturn moon rockets.

When I saw the exhibition, Sputnik was not even a quarter century in the past, but to me as a kid it was ancient history. In that time, people had orbited the Earth, gone to the Moon, sent robots throughout the solar system, and were about to launch the first reusable Space Shuttle.

Today is the 50th anniversary of that first-ever Sputnik orbital flight. As far as people going into space, not much genuinely new has happened since I saw those Soviet rockets. We have the space station now (built through cooperation between post-Soviet Russia, NASA, and other space programs around the world), but we're also still flying Soyuz and Shuttle missions, and no one has been back to the Moon since 1972.