Penmachine

31 October 2009

Links of interest (2009-10-31):

- The rotor on the new Grouse Mountain wind turbine is turning very slowly, first time I've seen it move. Must be testing.

- Notice that when they have all those many layers on, supermodels almost look like normal people?

- Sydney, Australia covered the road of the Harbour Bridge with grass and cows, and 6000 people had a picnic.

- "No child has been poisoned by a stranger's goodies on Halloween, ever, as far as we can determine."

- Brent Simmons on vaccines (via Daring Fireball). I had chicken pox almost as bad, but at 15. My wife Air got shingles in '04. I'm flad the kids will get neither.

- If, like many Canadians, you have a huge voice crush on Nora Young, then this audio from CBC's Spark will slay you.

- Awesome song flowcharts for "Total Eclipse of the Heart" and "Hey Jude."

- Dan Savage is always so cheecky: "I don't believe that couples who make the choice to be monogamous should be discriminated against in any way."

- Archaeology doc "The Link" a few months ago was full of needless hype. Discovery Channel's "Discovering Ardi" shows how it's done properly.

- "I'm all for winging it, but saying 'I'm not really prepared' to an audience shows them the ultimate disrespect."

- Some interesting iPhone photography apps.

- Dark areas on this world map are the most remote from a city. No Antarctica, though.

- A new deal today with the Cowichan band means you'll be able to buy real sweaters at HBC Olympic store.

- Twelve images showing how vastly digital imaging has improved astrophotography on the ground and in space since 1974.

- Seven questions that keep physicists awake at night (still lots to learn, which is great).

- First-ever Lip Gloss and Laptops video podcast (for Halloween).

- American Samoa could have had a tsunami warning system, but funds were frozen in 2007 because of waste and corruption.

- Telus is selling iPhones in Canada Thursday of this week (Nov 5). Pricing is basically the same as Rogers/Fido (no surprise).

- The opposing Canadian "No TV Tax" vs. "Local TV Matters" ads are indistinguishable, obnoxious, and make both sides look like shitheads. Makes me want to go out and get some man-on-the-street interviews. "Excuse me, ma'am, did you know that both the TV networks and the cable companies are wasting money on advertising instead of trying to make better programming, using fake man-on-the-street interviews to try to confuse you about their own pissing contest? What do you think of that?"

- Here's a flu primer. The October 25 edition of CBC's "Cross Country Checkup" (MP3) is also good. Here's a slightly contrary position, and a more general one about the dangers of not vaccinating. Wired also has a cover story on the topic.

- Weird Al's relentless perfectionism in the studio (love when he gets a headache trying to channel Zack de le Rocha).

- As of today it's been 32 years since the last case of smallpox in the world was eliminated by vaccination.

- The 27" iMac has a shockingly low price for what you get - even for the LCD panel alone (via Dave Winer).

- Dave Winer also notes why death of a parent can make you grown up. My parents are alive, and doing great (better than me!).

- I like Barbara Ehrenreich's new book, though I haven't read it yet.

- Two people I know both had cancer surgery the same day, this past Monday.

- Top 10 Internet rules (via Raincoaster).

- $400 is expensive, but if you make serious video with a DSLR, I bet this LCD viewfinder is worth it (via Scott Bourne).

- Having to medivac a sailor from a US Navy submarine to a helicopter offshore is hairy and dangerous business!

- As Paul Thurrott said, people are going to be wandering into Microsoft's new store all the time and asking, "Excuse me, where are the iPods?"

- "If what you're doing does make sense, then, for Christ's sake, talk like a human being."

- From Psychology Today in 2008, ten ways we get the odds wrong on risk.

- You can now buy the whole Abbey Road album for Beatles Rock Band.

- Daughter M just described a fever-induced time dilation hallucination identical to mine from childhood. Never thought anyone would understand!

- Red Javelin Communications is apparently working with my company Navarik, but I'm finding their website rather too buzzwordy for my taste.

- Research in Motion. Oh, what will we do with you and your fine, fine, not-at-all-dirty URL http://rim.jobs?

- A great (much improved) update by Billy Wilson to my very popular "All the Current DLSRs" camera collage.

- Here's a sign of flu in our neighbourhood: our local Shoppers Drug Mart was entirely sold out of hand sanitizer. Both my kids were stricken, but I avoided it.

- Noya sings with my band sometimes. Here's her solo video.

- Another Ralph Lauren Photoshop disaster.

- The Diamond Dave Soundboard is still genius.

- As always, Saturn's rings and moons are some of the strangest and most beautiful things you can see.

Labels: australia, beatles, cbc, environment, evolution, holiday, lipglossandlaptops, microsoft, photography, podcast, sex, vancouver, video

28 October 2009

Evolution book review: Dawkins's "Greatest Show on Earth," Coyne's "Why Evolution is True," and Shubin's "Your Inner Fish"

Next month, it will be exactly 150 years since Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859. This year also marked what would have been his 200th birthday. Unsurprisingly, there are a lot of new books and movies and TV shows and websites about Darwin and his most important book this year.

Next month, it will be exactly 150 years since Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859. This year also marked what would have been his 200th birthday. Unsurprisingly, there are a lot of new books and movies and TV shows and websites about Darwin and his most important book this year.

Of the books, I've bought and read the three of the highest-profile ones: Neil Shubin's Your Inner Fish (actually published in 2008), Jerry Coyne's Why Evolution is True, and Richard Dawkins's The Greatest Show on Earth: The Evidence for Evolution. They're all written by working (or, in Dawkins's case, officially retired) evolutionary biologists, but are aimed at a general audience, and tell compelling stories of what we know about the history of life on Earth and our part in it. I also re-read my copy of the first edition of the Origin itself, as well as legendary biologist Ernst Mayr's 2002 What Evolution Is, a few months ago.

Why now?

Aside from the Darwin anniversaries, I wanted to read the three new books because a lot has changed in the study of evolution since I finished my own biology degree in 1990. Or, I should say, not much has changed, but we sure know a lot more than we did even 20 years ago. As with any strong scientific idea, evidence continues accumulating to reinforce and refine it. When I graduated, for instance:

- DNA sequencing was rudimentary and horrifically expensive, and the idea of compiling data on an organism's entire genome was pretty much a fantasy. Now it's almost easy, and scientists are able to compare gene sequences to help determine (or confirm) how different groups of plants and animals are related to each other.

- Our understanding of our relationship with chimpanzees and our extinct mutual relatives (including Australopithecus, Paranthropus, Sahelanthropus, Orrorin, Ardipithecus, Kenyanthropus, and other species of Homo in Africa) was far less developed. With more fossils and more analysis, we know that our ancestors walked upright long before their brains got big, and that raises a host of new and interesting questions.

- The first satellite in the Global Positioning System had just been launched, so it was not yet easily possible to monitor continental drift and other evolution-influencing geological activities happening in real time (though of course it was well accepted from other evidence). Now, whether it's measuring how far the crust shifted during earthquakes or watching as San Francisco marches slowly northward, plate tectonics is as real as watching trees grow.

- Dr. Richard Lenski and his team had just begun what would become a decades-long study of bacteria, which eventually (and beautifully) showed the microorganisms evolving new biochemical pathways in a lab over tens of thousands of generations. That's substantial evolution occurring by natural selection, incontrovertibly, before our eyes.

- In Canada, the crash of Atlantic cod stocks and controversies over salmon farming in the Pacific hadn't yet happened, so the delicate balances of marine ecosystems weren't much in the public eye. Now we understand that human pressures can disrupt even apparently inexhaustible ocean resources, while impelling fish and their parasites to evolve new reproductive and growth strategies in response.

- Antibiotic resistance (where bacteria in the wild evolve ways to prevent drugs from being as effective as they used to) was on few people's intellectual radar, since it didn't start to become a serious problem in hospitals and other healthcare environments until the 1990s. As with cod, we humans have unwittingly created selection pressures on other organisms that work to our own detriment.

...and so on. Perhaps most shocking in hindsight, back in 1990 religious fundamentalism of all stripes seemed to be on the wane in many places around the world. By association, creationism and similar world views that ignore or deny that biological evolution even happens seemed less and less important.

Or maybe it just looked that way to me as I stepped out of the halls of UBC's biology buildings. After all, whether studying behavioural ecology, human medicine, cell physiology, or agriculture, no one there could get anything substantial done without knowledge of evolution and natural selection as the foundations of everything else.

Why these books?

The books by Shubin, Coyne, and Dawkins are not only welcome and useful in 2009, they are necessary. Because unlike in other scientific fields—where even people who don't really understand the nature of electrons or fluid dynamics or organic chemistry still accept that electrical appliances work when you turn them on, still fly in planes and ride ferryboats, and still take synthesized medicines to treat diseases or relieve pain—there are many, many people who don't think evolution is true.

No physicians must write books reiterating that, yes, bacteria and viruses are what spread infectious diseases. No physicists have to re-establish to the public that, honestly, electromagnetism is real. No psychiatrists are compelled to prove that, indeed, chemicals interacting with our brain tissues can alter our senses and emotions. No meteorologists need argue that, really, weather patterns are driven by energy from the Sun. Those things seem obvious and established now. We can move on.

But biologists continue to encounter resistance to the idea that differences in how living organisms survive and reproduce are enough to build all of life's complexity—over hundreds of millions of years, without any pre-existing plan or coordinating intelligence. But that's what happened, and we know it as well as we know anything.

If the Bible or the Qu'ran is your only book, I doubt much will change your mind on that. But many of the rest of those who don't accept evolution by natural selection, or who are simply unsure of it, may have been taught poorly about it back in school—or if not, they might have forgotten the elegant simplicity of the concept. Not to mention the huge truckloads of evidence to support evolutionary theory, which is as overwhelming (if not more so) and more immediate than the also-substantial evidence for our theories about gravity, weather forecasting, germs and disease, quantum mechanics, cognitive psychology, or macroeconomics.

Enjoying the human story

So, if these three biologists have taken on the task of explaining why we know evolution happened, and why natural selection is the best mechanism to explain it, how well do they do the job? Very well, but also differently. The titles tell you.

Shubin's Your Inner Fish is the shortest, the most personal, and the most fun. Dawkins's The Greatest Show on Earth is, well, the showiest, the biggest, and the most wide-ranging. And Coyne's Why Evolution is True is the most straightforward and cohesive argument for evolutionary biology as a whole—if you're going to read just one, it's your best choice.

However, of the three, I think I enjoyed Your Inner Fish the most. Author Neil Shubin was one of the lead researchers in the discovery and analysis of Tiktaalik, a fossil "fishapod" found on Ellesmere Island here in Canada in 2004. It is yet another demonstration of the predictive power of evolutionary theory: knowing that there were lobe-finned fossil fish about 380 million years ago, and obviously four-legged land dwelling amphibian-like vertebrates 15 million years later, Shubin and his colleagues proposed that an intermediate form or forms might exist in rocks of intermediate age.

Ellesmere Island is a long way from most places, but it has surface rocks about 375 million years old, so Shubin and his crew spent a bunch of money to travel there. And sure enough, there they found the fossil of Tiktaalik, with its wrists, neck, and lungs like a land animal, and gills and scales like a fish. (Yes, it had both lungs and gills.) Shubin uses that discovery to take a voyage through the history of vertebrate anatomy, showing how gill slits from fish evolved over tens of millions of years into the tiny bones in our inner ear that let us hear and keep us balanced.

Since we're interested in ourselves, he maintains a focus on how our bodies relate to those of our ancestors, including tracing the evolution of our teeth and sense of smell, even the whole plan of our bodies. He discusses why the way sharks were built hundreds of millions of years ago led to human males getting certain types of hernias today. And he explains why, as a fish paleontologist, he was surprisingly qualified to teach an introductory human anatomy dissection course to a bunch of medical students—because knowing about our "inner fish" tells us a lot about why our bodies are this way.

Telling a bigger tale

Richard Dawkins and Jerry Coyne tell much bigger stories. Where Shubin's book is about how we people are related to other creatures past and present, the other two seek to explain how all living things on Earth relate to each other, to describe the mechanism of how they came to the relationships they have now, and, more pointedly, to refute the claims of people who don't think those first two points are true.

Dawkins best expresses the frustration of scientists with evolution-deniers and their inevitable religious motivations, as you would expect from the world's foremost atheist. He begins The Greatest Show on Earth with a comparison. Imagine, he writes, you were a professor of history specializing in the Roman Empire, but you had to spend a good chunk of your time battling the claims of people who said ancient Rome and the Romans didn't even exist. This despite those pesky giant ruins modern Romans have had to build their roads around, and languages such as Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, French, German, and English that are obviously derived from Latin, not to mention the libraries and museums and countrysides full of further evidence.

He also explains, better than anyone I've ever read, why various ways of determining the ages of very old things work. If you've ever wondered how we know when a fossil is 65 million years old, or 500 million years old, or how carbon dating works, or how amazingly well different dating methods (tree ring information, radioactive decay products, sedimentary rock layers) agree with one another, read his chapter 4 and you'll get it.

Alas, while there's a lot of wonderful information in The Greatest Show on Earth, and many fascinating photos and diagrams, Dawkins could have used some stronger editing. The overall volume comes across as scattershot, assembled more like a good essay collection than a well-planned argument. Dawkins often takes needlessly long asides into interesting but peripheral topics, and his tone wanders.

Sometimes his writing cuts precisely, like a scalpel; other times, his breezy footnotes suggest a doddering old Oxford prof (well, that is where he's been teaching for decades!) telling tales of the old days in black school robes. I often found myself thinking, Okay, okay, now let's get on with it.

Truth to be found

On the other hand, Jerry Coyne strikes the right balance and uses the right structure. On his blog and in public appearances, Coyne is (like Dawkins) a staunch opponent of religion's influence on public policy and education, and of those who treat religion as immune to strong criticism. But that position hardly appears in Why Evolution is True at all, because Coyne wisely thinks it has no reason to. The evidence for evolution by natural selection stands on its own.

I wish Dawkins had done what Coyne does—noting what the six basic claims of current evolutionary theory are, and describing why real-world evidence overwhelmingly shows them all to be true. Here they are:

- Evolution: species of organisms change, and have changed, over time.

- Gradualism: those changes generally happen slowly, taking at least tens of thousands of years.

- Speciation: populations of organisms not only change, but split into new species from time to time.

- Common ancestry: all living things have a single common ancestor—we are all related.

- Natural selection: evolution is driven by random variations in organisms that are then filtered non-randomly by how well they reproduce.

- Non-selective mechanisms: natural selection isn't the only way organisms evolve, but it is the most important.

The rest of Coyne's book, in essence, fleshes those claims and the evidence out. That's almost it, and that's all it needs to be. He recounts too why, while Charles Darwin got all six of them essentially right back in 1859, only the first three or four were generally accepted (even by scientists) right away. It took the better part of a century for it to be obvious that he was correct about natural selection too, and even more time to establish our shared common ancestry with all plants, animals, and microorganisms.

Better than other books about evolution I've read, Why Evolution is True reveals the relentless series of tests that Darwinism has been subjected to, and survived, as new discoveries were made in astronomy, geology, physics, physiology, chemistry, and other fields of science. Coyne keeps pointing out that it didn't have to be that way. Darwin was wrong about quite a few things, but he could have been wrong about many more, and many more important ones.

If inheritance didn't turn out to be genetic, or further fossil finds showed an uncoordinated mix of forms over time (modern mammals and trilobites together, for instance), or no mechanism like plate tectonics explained fossil distributions, or various methods of dating disagreed profoundly, or there were no imperfections in organisms to betray their history—well, evolutionary biology could have hit any number of crisis points. But it didn't.

Darwin knew nothing about some of these lines of evidence, but they support his ideas anyway. We have many more new questions now too, but they rest on the fact of evolution, largely the way Darwin figured out that it works.

The questions and the truth

Facts, like life, survive the onslaughts of time. Opponents of evolution by natural selection have always pointed to gaps in our understanding, to the new questions that keep arising, as "flaws." But they are no such thing: gaps in our knowledge tell us where to look next. Conversely, saying that a god or gods, some supernatural agent, must have made life—because we don't yet know exactly how it happened naturally in every detail—is a way of giving up. It says not only that there are things we don't know, but things we can never learn.

Some of us who see the facts of evolution and natural selection, much the way Darwin first described them, prefer not to believe things, but instead to accept them because of supporting scientific evidence. But I do believe something: that the universe is coherent and comprehensible, and that trying to learn more about it is worth doing for its own sake.

In the 150 years since the Origin, people who believed that—who did not want to give up—have been the ones who helped us learn who we, and the other organisms who share our planet, really are. Thousands of researchers across the globe help us learn that, including Dawkins exploring how genes, and ideas, propagate themselves; Coyne peering at Hawaiian fruit flies through microscopes to see how they differ over generations; and Shubin trekking to the Canadian Arctic on the educated guess that a fishapod fossil might lie there.

The writing of all three authors pulses with that kind of enthusiasm—the urge to learn the truth about life on Earth, over more than 3 billion years of its history. We can admit that we will always be somewhat ignorant, and will probably never know everything. Yet we can delight in knowing there will always be more to learn. Such delight, and the fruits of the search so far, are what make these books all good to read during this important anniversary year.

Labels: anniversary, books, controversy, evolution, religion, review, science

26 October 2009

Odds videos

When I learned to play rock music back in the '80s, Vancouver's Odds (and their cover-band alter-ago The Dawn Patrol) were among my key inspirations. I got to know some of the guys in the band too. In the last five or six years, Odds bassist Doug Elliott has also become a good friend, as well as playing bass sometimes in my band.

After a hiatus of close to a decade, the Odds returned with a tweaked lineup of musicians and a new album, Cheerleader, last year, and now they've posted all their music videos dating back to 1991 on YouTube. They're worth a look and a listen. I think "Someone Who's Cool" is still my favourite:

Although the big suit shoulders and done-to-the-neck dress shirts of the early-'90s ones have a certain retro appeal too. Make sure you read the little descriptions by the band.

Some of the best Odds songs combine the intelligence of Elvis Costello with the booty-shaking overdriven guitar boogie of AC/DC, and that's a hard balance to accomplish.

Labels: band, friends, music, odds, video, youtube

24 October 2009

What would you do for a Klondike bear?

A couple of weeks ago, my wife Air pointed out to me that the sidewalks in front of convenience stores throughout Greater Vancouver have recently sprouted large, inflatable polar bears promoting Klondike ice cream bars:

The Klondike promotions rep was obviously very busy around Vancouver in October. Both Air and I like the inflatable bears—they're cute, and large, and strange. Most effectively, they point out how many independent mom-and-pop style corner stores there still are in this city. I'm often tempted to assume that most have been put out of business by 7-Eleven and gas station shops, but that appears not to be the case.

My set of nine photos above resulted from my simply keeping an eye out for the bears during a couple of car trips on a single day this past week. Most of the pictures are from just one street, the main inter-city artery Kingsway. There must be dozens or hundreds of the beasts throughout the region.

One I didn't manage to snap is probably breaking the rules. On Canada Way, there's an independent Buffalo gas station that has covered the Klondike logo with a sign reading "HAND CAR WASH." That promo rep might be angry if he or she spots it.

Labels: animals, food, humour, shopping, signs, vancouver

22 October 2009

Spin my ribcage

Derived from the same CT scan of my body taken a few weeks ago is this 3D movie, also made with the open-source OsiriX software:

You can clearly see my portacath, which showed up just as well as my ribs. Freaky.

Labels: cancer, chemotherapy, ctscan, geekery, photography, science, software, videogames

21 October 2009

Killing upgrades dead

John Gruber points to this article about PC upgrades by Marco Arment:

The upgrade market for average PC owners is dead. We killed it. [...]

In 1998, when everyone was happily using long filenames and browsing the internet and playing their first MP3s and editing their first scanned photos to email to their relatives, a five-year-old computer couldn't easily do any of these things.

But what common tasks in 2009 can't be accomplished by a 2.8 GHz Pentium 4 PC with Windows XP SP2 and a cable internet connection—the average technology of 2004? Not much that regular people actually do.

That reminded me of something Geoff Duncan wrote at least five years ago, which I can no longer find anywhere online:

Your average PC user doesn't update anything. They just throw the computer away when it stops working and buy a new one, then don't change the software on it either for fear of breaking something.

Things haven't changed much, but we'll see if enough people need new computers in the next little while to give Windows 7 a boost. Microsoft's new operating system comes out this week.

Labels: geekery, microsoft, windows, windows7

20 October 2009

See my cancer

Here, take a look at this extremely cool and scientifically amazing picture:

That's me, via a few slices from my latest CT scan, taken at the end of September 2009. I opened the files provided to me by the B.C. Cancer Agency's Diagnostic Imaging department using the open-source program OsiriX, giving me my first chance to take a first-hand look at my cancer in almost a year. Before that, the I'd only seen my original colon tumour on the flexible sigmoidoscopy camera almost three years ago.

I've circled the biggest lung tumours metastasized from my original colon cancer (which was removed by surgery in mid-2007). You can see the one in my upper left lung and two (one right behind the other) in my lower left lung. There are six more tumours, all smaller, not easily visible in this view. I'm not a radiologist, so I couldn't readily distinguish the smallest ones from regular lung matter and other tissue. Nevertheless, now we can all see what I'm dealing with.

These blobs of cancer have all grown slightly since I started treatment with cediranib in November 2008. To my untrained eye, the view doesn't look that different from the last time I saw my scan in December of that year, which is fairly good as far as I'm concerned. Not as good as if they'd stabilized or shrunk, but better than many other possibilities.

Labels: cancer, chemotherapy, ctscan, geekery, photography, science, software, video

19 October 2009

Links of interest (2009-10-19):

From my Twitter stream:

- My dad had cataract surgery, and now that eye has perfect vision—he no longer needs a corrective lens for it for distance (which, as an amateur astronomer, he likes a lot).

- Darren's Happy Jellyfish (bigger version) is my new desktop picture.

- Ten minutes of mesmerizing super-slo-mo footage of bullets slamming into various substances, with groovy bongo-laden soundtrack.

- SOLD! Sorry if you missed out.

I have a couple of 4th-generation iPod nanos for sale, if you're interested. - Great backgrounder on the 2009 H1N1 flu virus—if you're at all confused about it, give this a read.

- The new Nikon D3s professional digital SLR camera has a high-gain maximum light sensitivity of ISO—102,400. By contrast, when I started taking photos seriously in the 1980s, ISO—1000 film was considered high-speed. The D3s can get the same exposure with 100 times less light, while producing perfectly acceptable, if grainy, results.

- Nice summary of how content-industry paranoia about technology has been wrong for 100 years.

- The Obama Nobel Prize makes perfect sense now.

- I like these funky fabric camera straps (via Ken Rockwell).

- I briefly appear on CBC's "Spark" radio show again this week.

- Here's a gorilla being examined in the same type of CT scan machine I use every couple of months. More amazing, though, is the mummified baby woolly mammoth. Wow.

- As I discovered a few months ago, in Canada you can use iTunes gift cards to buy music, but not iPhone apps. Apple originally claimed that was comply with Canadian regulations, but it seems that's not so—it's just a weird and inexplicable Apple policy. (Gift cards work fine for app purchases in the U.S.A.)

- We've released the 75th episode of Inside Home Recording.

- These signs from The Simpsons are indeed clever, #1 in particular.

- Since I so rarely post cute animal videos, you'd better believe that this one is a doozy (via Douglas Coupland, who I wouldn't expect to post it either).

- If you're a link spammer, Danny Sullivan is quite right to say that you have no manners or morals, and you suck.

- "Lock the Taskbar" reminds me of Joe Cocker, translated.

- A nice long interview with Scott Buckwald, propmaster for Mad Men.

Labels: animals, apple, biology, cartoon, geekery, humour, insidehomerecording, iphone, ipod, itunes, linksofinterest, nikon, photography, politics, science, surgery, television, video, web

18 October 2009

Sunday night

It's Sunday night and I'm not sleepy. Well, I am, but I can't sleep, don't really want to yet. Everyone else in the house is down for the count until morning. I've always enjoyed this time, taking me back to being an only child alone with my thoughts—except my wonderful wife is breathing beside me in bed, which is much better, and endlessly comforting.

But tonight's not happy, or sad. It just is. Every day is a fight. Every. Fucking. Day. And every night too. Not a fight with a person, but with my own cells, useless greasy tissues that don't belong where they're growing in my lungs. I never know how much of my pain and fatigue is from them, and how much from the punishing medicine that slows the rate of cancer cell division inside me.

I spent a lot of this weekend in the bathroom. I don't know if that's a pattern yet, or just a rough few days of side effects. (But not as rough as some have been.) I cooked a pretty nice tikka masala dish tonight, and my wife brought home a lemon meringue pie for dessert. Our dinner with the kids at the kitchen table was my best part of Sunday.

Sometimes, like now, I don't want to sleep because I don't know what I'll be like when I wake up. Will I feel better, worse, the same? I can't predict, but at least I'm confident I will wake up. Will I sleep well, and rise rested, or toss and turn? Or will I be in the bathroom again, perhaps for hours? I don't really know.

I try to live day by day, but you have to plan something, even if your plans fall through. I have a few plans for tomorrow, and maybe I'll get to some of them. Or at least one. Or, just maybe if tonight goes poorly, none. These are my days and nights, more than three years after I developed cancer, and almost three years after I found out about the first (but not the worst) of it.

A fight. Every. Fucking. Day. And night. And more tomorrow. Time to sleep now, I think. To be ready.

Labels: cancer, chemotherapy, family, fatigue, pain

15 October 2009

Sinking feeling

Today, as part of Blog Action Day, I've agreed to write about the environment and climate change. I've done that here many times before, generally in a positive way, or at least a frustrated one. But not today.

Today, as part of Blog Action Day, I've agreed to write about the environment and climate change. I've done that here many times before, generally in a positive way, or at least a frustrated one. But not today.

Maybe I'm just in a pessimistic mood, but honestly, I'm starting to think we're screwed. There are honest moves afoot, especially in Europe, to change patterns of human energy consumption and reduce carbon emissions. But here in North America, where we use more energy per person than all but a few very small countries, we're doing essentially nothing.

I first became aware of increasing human effects on the Earth's climate around Earth Day in 1990, almost 20 years ago, which was a pretty high-profile event. For awhile after that, there were lots of recycled products in the grocery stores, and talk of converting away from oil, gas, and coal to heat our houses, generate our electricity, and power our vehicles.

And then things slid back roughly to where they were before. Paper towels and toilet paper went from recycled brown to bleached white again. As the economy boomed, people who never went off-road or hauled lumber bought huge Hummers and pickup trucks. Politicians, businesspeople, activists, and others expended a lot of words about the problem of climate change. Yet here in Canada, while we've improved the efficiency of what we do, our overall emissions keep going up, despite our promises.

In the United States and Canada, we're distracted by economic crises and healthcare reform and celebrity scandals and cable reality shows. The developing world is growing too fast not to increase their own emissions. Europe and other countries making efforts aren't enough. By the time sea levels start rising in earnest and the social and political disruptions start, we probably won't be able to keep climates from changing all around the world.

So in all likelihood, we'll wait too long, and we'll have to adapt as our environment alters wildly around us. That will be expensive, disruptive, and probably bloody in all sorts of ways.

I'm not saying we should give up and do nothing, but right now it seems that, collectively, we (and I'm fully including myself here) are very nearly doing nothing by default. Since I have cancer, I don't know if I'll be around to see what happens in a few decades. But my kids will. They will most probably, as the curse goes, live in interesting times.

Labels: americas, blog, canada, environment, linkbait, news, politics

14 October 2009

iPods across oceans and continents

When we sold our old laptop recently, we used the money to buy a couple of iPod touches for our kids. I know, we spoil them terribly and all that. Ours is a geek house. Get used to it. (And if you're interested in their old iPod nanos, those are for sale too—let me know.)

Ordering online, I presumed (naively) that while the iPods are of course made in China, there would probably be a North American distribution centre where they are individually laser engraved and then shipped to customers here. But Apple and UPS let you track your order. Ours shipped directly out of China, and the results are a bit depressing.

There's been a lot of hoopla about Apple pulling out of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce over the Chamber's poor climate-change policies, Apple's greener laptops made with more recyclable materials, and so on, but I have to wonder whether many of those efforts are being negated by the insanely inefficient transport routes taken by items shipped from the online Apple Store.

Although I ordered two identical devices (with separate custom engraving on the back of each) at the same time, as part of the same order, here's how the two iPods are getting to our house:

- iPod #1: Shanghai, China → Anchorage, Alaska → Louisville, Kentucky → Buffalo, New York → Mount Hope, Ontario → Winnipeg, Manitoba → Calgary, Alberta → Richmond, B.C. → Burnaby, B.C.

- iPod #2: Shanghai, China → Anchorage, Alaska → Louisville, Kentucky → Lachine, Québec → Montréal, Québec → Mount Hope, Ontario → Calgary, Alberta → Richmond, B.C. → Burnaby, B.C

Same order, same type of device, same factory. But apparently, the most cost-effective way to get them to me was to send them together from Shanghai to Anchorage to Louisville, then to separate them, sending one via New York, Ontario, Manitoba, and Alberta, and the other via Québec, Ontario, and Alberta. Both passed through Mount Hope and Calgary, but at different times. They're both now in Richmond on the way here to Burnaby, hopefully on the same truck (but I'm not sure of that—see below for an unimpressive update).

It's about 9,000 km direct from Shanghai to Vancouver by plane, but on these routes each iPod has traveled almost twice that far (around 17,000 km) by plane and truck, with takeoffs, landings, and transfers. I know the packages are small, but the price of shipping that way can't possibly be taking into account the relative energetic and environmental costs of the two routes.

Never mind that, by essentially excluding environmental effects, it's less expensive to manufacture the iPods an ocean away to start with. How do these transactions add up, when you multiply them by the millions?

If we're interested in ameliorating climate change, I think that we'll have to address the mismatch between the monetary efficiency and energetic inefficiency of these haphazard transportation methods. But that will likely mean that our gadgets will get more expensive in the short term, in order to make our lives more tolerable in the long term. I have a feeling that, with our generally shortsighted human thinking, we might not be willing to accept that.

And that's a bit of a bummer.

UPDATE 11:30 a.m.: There's something amusing about the situation now. Both iPods arrived at Vancouver International Airport in Richmond before sunrise this morning, after making their way halfway around the world, rapid-fire, in five days. But they've now, apparently, been sitting at YVR, about 12 km away from my house, for three and a half hours without being loaded on a truck, because of "adverse weather conditions." What are those conditions? It's raining a bit. In Vancouver, in the autumn.

FURTHER UPDATE 2:00 p.m.: Delivery. Of one of the iPods. They were both at the airport, both supposedly delayed by weather (though it's sunny now), and one got put on a truck and arrived at the house a few minutes ago. The other one, presumably, is coming on another truck. Point reinforced. Next time I'll buy retail, where I can at least assume that two of the same product from the same batch came to the store in the same vehicle.

FINAL UPDATE 5:00 p.m.: The delay of the second shipment at YVR is a mystery even to the friendly UPS phone rep. It will be delivered tomorrow, taking longer to travel the 12 km from the airport to my house than it did to traverse the 3500 km from Ontario to the West Coast yesterday.

Labels: apple, china, environment, ipod, transportation, vancouver

13 October 2009

Growth of the City of Glass

Dave Winer has posted a bunch of photos from his parents, reaching back more than 50 years. A picture of Vancouver's Coal Harbour from his family trip here in the '60s is fascinating, because here's a similar view today.

Things have changed a little. If you open the two images in separate windows or browser tabs and look carefully, you might be able to spot a couple of the same buildings.

Labels: davewiner, history, photography, vancouver

11 October 2009

The slow history of Vancouver

Vancouver historian Chuck Davis has been writing a series of posts for re:place magazine about the city, summarizing a single year of the city's history each time. The series is called "A Year in Five Minutes," though I think you'd have to read pretty fast to get through each entry in that little time.

He's just reached 1938 and 1939, the years my mother (here in Vancouver) and father (in Berlin) were born, respectively. You can visit the Year in Five Minutes category regularly, or subscribe to the RSS feed for those stories. I'm finding them an enjoyable read. Fellow Vancouverites, former residents, or other B.C. history buffs might too.

Labels: blog, history, vancouver, web

09 October 2009

Myriad type choices

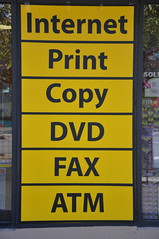

This week I walked around our neighbourhood a bit and took some photos of signs. I'm not much of a typeface nerd, but I did notice something.

Some years ago, when I designed the first version of penmachine.com, I created the logo header using the font Myriad, which I've liked for a long time:

Various weights and styles of Myriad have become my go-to Penmachine fonts, for the cover of my 2005 album, as titles for videos, and so on. When I picked Myriad, I didn't find it too common. But over the past two or three years, it's started showing up more often elsewhere. Here were a couple of examples from my walk:

Myriad is versatile and friendly, so I'm not surprised that I'm seeing it more. Of course, there are also lots of... uh... less elegant choices out there:

If you ever wonder what a particular font is, WhatTheFont.com lets you point to or upload a picture and will try to figure it out automatically for you. It doesn't always work, but especially if you have a clean image, it often does a good job.

Labels: font, geekery, vancouver

06 October 2009

Telus and Bell go iPhone in Canada

Things have been all a-twitter about Canadian mobile carriers Bell and Telus (my cell phone provider) starting to sell Apple's iPhone, supposedly next month. My wife Air told me the scoop yesterday, and I was surprised, and skeptical.

But it sounds like it's really happening. This is a bigger deal than it seems if you don't follow the mobile phone industry, for two reasons:

- In most markets, Apple has an exclusive arrangement with a single carrier to sell the iPhone. Until now in Canada, that has been with Rogers Wireless and its subsidiary Fido, and in the U.S. it remains AT&T Wireless. Having competing carriers all with the iPhone is unusual.

- The iPhone uses the most common mobile phone radio standard in the world, known as GSM. However, until now both Bell and Telus have used a competing and incompatible standard, CDMA, also used by Verizon and Sprint in the U.S.A.

In North America, many mobile phones (such as BlackBerry devices) come in both CDMA and GSM versions for different carriers, but the iPhone has been GSM-only since its introduction in 2007. It turns out that Bell and Telus have been installing some GSM technology on their cellular towers for at least a year, and planning to have it ready for many customers in 2010.

But now it looks like they'll be early, and the iPhone may be their first big rollout of 3G (third-generation) GSM wireless. And although it will be awhile, my old CDMA phone is likely on the way to becoming obsolete. Qualcomm, which owns the CDMA patents and licenses them to carriers and device makers, had better be looking for some new way to make money.

Labels: apple, canada, geekery, iphone, telecommunications, telus

05 October 2009

Nominate our shows for the Podcast Awards?

I'm the co-host of Inside Home Recording and engineer for Lip Gloss and Laptops, my wife's podcast. We're trying the usual social-media methods of garnering nominations for the annual Podcast Awards, which have been running for a few years now and are organized by Todd Cochrane of Geek News Central.

I'm the co-host of Inside Home Recording and engineer for Lip Gloss and Laptops, my wife's podcast. We're trying the usual social-media methods of garnering nominations for the annual Podcast Awards, which have been running for a few years now and are organized by Todd Cochrane of Geek News Central.

If you'd like to help out, here's what I'd ask you to do by the deadline of October 18, 2009:

- Please go to PodcastAwards.com.

- In the People's Choice and Health/Fitness categories, fill in Lip Gloss and Laptops and its URL, www.lipglossandlaptops.com.

- In the Best Produced and Education categories, fill in Inside Home Recording and its URL, www.insidehomerecording.com.

- Do not nominate either show for any other categories. Each show is only allowed two nominations (one of the top categories, and one regular one), and we don't want to be disqualified or to dilute the vote. (Inside Home Recording, for instance, is more likely to get a nomination in Education, because Technology is crowded with popular podcasts.)

- Feel free to fill in any other podcasts you like in other categories. But do it all at once, because you can only submit the ballot once per person.

- Add your name and email address to the bottom of the form (Todd has tremendous integrity—he's not going to sell or reuse your info).

- Check your form over, and submit it.

- Maybe tell your friends.

Remember, the deadline is October 18. I'll let you know when the actual voting begins after that, especially if either of our podcasts get in. And of course, please subscribe to the shows if you don't already!

Labels: insidehomerecording, linkbait, lipglossandlaptops, podcast

02 October 2009

Ardi is another fascinating hominid fossil, but "missing link" no longer makes sense

First, let's get something out of the way: the term missing link has long been useless, especially in human palaeontology. That's reinforced by this week's publication of a special issue of the journal Science, focusing on the 4.4-million-year-old skeleton of Ardipithecus ramidus, nicknamed "Ardi."

First, let's get something out of the way: the term missing link has long been useless, especially in human palaeontology. That's reinforced by this week's publication of a special issue of the journal Science, focusing on the 4.4-million-year-old skeleton of Ardipithecus ramidus, nicknamed "Ardi."

Chimpanzees are the closest living relative to human beings in the world, but our common ancestor lived a long time ago—at least 6 million years, likely more. When Charles Darwin proposed, some 150 years ago, that the fossil links between humans and chimps were likely to be found in Africa, he was right, but at the time those links really were missing.

It took a few decades until the first Homo erectus fossils were found in Asia. Since then, palaeontologists have found many different skeletons and skeletal parts of Homo, Paranthropus, and Australopithecus, with the oldest, as predicted, all in Africa. We've been filling in our side of the chimp-human family tree for over a century. (The chimpanzee lineage has been more difficult, probably because their ancestors' forest habitats are less prone to preserving fossils—and we're less prone to paying as much attention to it too.)

So it's been a long time since the links were missing, and the term missing link is now more misleading than helpful. Like "Ida," the 47-million-year-old primate revealed with too much hype earlier this year, "Ardi" is no missing link, but she is another fascinating fossil showing interesting things about our ancestry. Most notably, she walked upright as we do, but had a much smaller brain, more like other apes—as well as feet that remained better for climbing trees than ours.

None of that should be shocking. We shouldn't expect any common ancestor of chimps and humans to be more like either one of us, since both lineages have kept evolving these past 6 million years. Ardi isn't a common ancestor—she's more closely related to humans than to chimps, and accordingly shows more human characteristics (or, perhaps better, we show characteristics more like hers), like bipedal walking and flexible wrists. That's extremely cool.

Also interestingly, "Ardi" is not new. It's taken researchers more than 15 years to analyze her, and similar fossils found nearby in Ethiopa's Afar desert. Simply teasing the extremely fragile, powdery fossil materials out of the soil without destroying them took years. Science can sometimes be a painstaking process, not for those who lack patience.

Labels: africa, controversy, evolution, history, science