Penmachine

26 April 2010

Two more arguments for learning statistics

One of my repeated themes here over the years is how genuinely lousy the human brain is at intuitively understanding probability and statistics. Two articles this week had me thinking about it again.

The first was Clive Thompson's latest opinion piece in Wired, "Why We Should Learn the Language of Data," where he argues for significantly more education about stats and probability in school, and in general, because:

If you don't understand statistics, you don't know what's going on—and you can't tell when you're being lied to.

Climate change? The changing state of the economy? Vaccination? Political polls? Gambling? Disease? Making decisions about any of them requires some understanding of how likelihoods and big groups of numbers interact in the world. "Statistics," Thompson writes, "is the new grammar."

The second article explains a key example. At the NPR Planet Money blog (incidentally, the Planet Money podcast is endlessly fascinating, the only one clever enough to get me interested in listening to business stories several times a week), Jacob Goldstein describes why people place bad bets on horse races.

After exhaustive statistical analyses (alas, this stuff isn't easy), economists Erik Snowberg and Justin Wolfers have figured out that even regular bettors at the track simply misperceive how bad their bets are, especially when wagering on long shots—those outcomes that are particularly unlikely, but pay off big if you win, because:

...people overestimate the probability of very rare events. "We're dreadful at perceiving the difference between a tiny probability and a small probability."

In our heads, extremely unlikely things (being in a commercial jet crash, for instance) seem just as probable, or even more probable, than simply somewhat unlikely things (being in a car crash on the way to the airport). That has us make funny decisions. For instance, on occasion couples (parents of young children, perhaps) choose to fly on separate planes so that, in the rare event that a plane crashes, one of them survives. But they both take the same car to the airport—as well as during much of the rest of their lives—which is far, far more likely to kill them both. (Though still not all that likely.)

Unfortunately, so much of probability is counterintuitive that I'm not sure how well we can educate ourselves about it for regular day-to-day decision-making. Even bringing along our iPhones, I don't think we should be using them to make statistical calculations before every outing or every meal. Besides, we could be so distracted by the little screens that we step out into traffic without noticing.

Our minds are required be good at filtering out irrelevancies, so we're not overwhelmed by everything going on around us. But the modern world has changed what's relevant, both to our daily lives and to our long-term interests. The same big brains that helped us make it that way now oblige us to think more carefully about what we do, and why we do it.

Labels: airport, games, magazines, podcast, probability, psychology, radio, transportation

14 March 2010

The privacy transition

A few weeks ago, my daughter Marina, who's 12, asked me to start mentioning her by name on this website, and when I link to her blog, photos of her on Flickr, the new blog she just set up with her sister, and so on.

A few weeks ago, my daughter Marina, who's 12, asked me to start mentioning her by name on this website, and when I link to her blog, photos of her on Flickr, the new blog she just set up with her sister, and so on.

Until now, I've been pretty careful about just calling her "M" or "Miss M," because while I'm personally comfortable putting my own name and information on the Web, that's not a decision I should have been making for my kids, especially before they were able to understand what its implications are. (For similar reasons, here on the blog I generally refer to my wife by her nickname Air, at her request.)

But Marina has started to find that annoying, because when she searches for "Marina Miller," she nearly always finds other people instead. She's starting to build herself an online profile—and the first component of that is establishing her online existence.

I was online around that age too, but at the turn of the 1980s it was a very different thing. In fact, no one expected to be themselves: we all used pseudonyms, like CB radio handles. And it was a much smaller, geekier community—or rather, communities. I had no Internet access until the decade was over, so connections were local, and each bulletin board system (BBS) was its own island, accessed by dialup modem, often by one person at a time. The Web hadn't been invented, and the concept of a search engine or a perpetual index of my online life was incomprehensible.

On a recent episode of CBC Radio's "Spark," Danah Boyd, who researches these things, noted that today's adults often look at our online exposure in terms of what can go wrong, while our younger compatriots and children look at it in terms of its benefits, or what can go right. It's not that they don't care about privacy, but that they understand it differently.

Marina is now closer to adulthood than toddlerhood, and her younger sister, at 10, is not far behind. I think that's a bit hard for any parent to accept, but in the next few years both our daughters have to (and will want to) learn to negotiate the world, online and offline, on their own terms. Overprotective helicopter parenting is a temptation—or today, even an expectation—but it's counterproductive. Just like we all need to learn to walk to school by ourselves, we all need to learn how to live our lives and assess risks eventually. I'd rather not wait until my kids are 18 or 19 and only then let them sink or swim on their own.

I think I share the more optimistic view about being myself on the Web because, unlike many people over 40 today, I have been online since even before my teens, and I've seen both the benefits and the risks of being public there. I hope my experience can help Marina and her sister L (who hasn't yet asked me to go beyond her initial) negotiate that landscape in the next few years.

That is, if they continue to want my help!

Labels: blog, controversy, family, geekery, probability, web

14 January 2010

Quake risks

Five years ago I wrote a long series of posts about the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, compiling information from around the Web and using my training in marine biology and oceanography to help explain what happened. Nearly 230,000 people died in that event.

Five years ago I wrote a long series of posts about the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, compiling information from around the Web and using my training in marine biology and oceanography to help explain what happened. Nearly 230,000 people died in that event.

Tuesday's magnitude-7 quake in Haiti looks to be a catastrophe of similar scale. I first learned of it through Twitter, which seems to be a key breaking-news technology now. Hearing that it was 7.0 on the Richter scale and was centred on land, only 25 kilometres from Port-au-Prince, I immediately thought, "Oh man, this is bad."

And it is. Some 50,000 are dead already, and more will die among the hundreds of thousands injured or missing. Haiti is, of course, one of the world's poorest countries, which makes things worse. Learning from aid efforts around the Indian Ocean in 2005 and from other disasters, the Canadian government is offering to match donations from Canadians for relief in Haiti.

This is a reminder that we live on a shifting, active planet, one with no opinions or cares about us creatures who cling like a film on its thin surface. We have learned, recently, to forecast weather, and to know where dangers from earthquakes, volcanoes, floods, storms, and other natural risks might lie. But we cannot predict them precisely, and some of the places people most like to live—flat river valleys, rich volcanic soils, fault-riddled landscapes, monsoon coastlines, tornado-prone plains, steep hillsides—are also dangerous.

Worse yet, the danger may not express itself over one or two or three human lifetimes. My city of Vancouver is in an earthquake zone, and also sits not far from at least a couple of substantial volcanoes. Yet it has been a city for less than 125 years. Quakes and eruptions happen in this region all the time—on a geological timescale. That still means that there has been no large earthquake or volcanic activity here since before Europeans arrived.

We would, I hope, do better than Port-au-Prince in a similar earthquake, but such chaos is not purely a problem of the developing world. The Earth, nature, and the Universe don't take any of our needs into account (no matter what foolishness people like Pat Robertson might say). We are at risk all over the world, and when the worst happens, we need to help each other.

Labels: americas, disaster, probability, science

30 May 2009

Luck and randomness

Randomness works in strange ways, at least as far as our minds are concerned. The stars in the sky are distributed essentially randomly (from our viewpoint), yet we see patterns in them—that's because a random distribution is clumpy, not even.

Since our brains seek patterns, we tend to see patterns in random things, like clouds, stains, or the browned surfaces on pieces of toast.

Now check this out: New Jersey grandmother Patricia Demauro played craps at a casino, and rolled a pair of dice 154 times without ever rolling a seven, over the course of more than four hours. The odds? 1.56 trillion to one against. But it happened.

It wasn't impossible, just supremely improbable. Yup, that's random.

Labels: americas, games, probability, psychology

03 May 2009

Children are safe, and should be outside

Lenore Skenazy's Free-Range Kids sounds like a fascinating book (she has an accompanying blog too). Her argument, essentially, is that the crime rate today is equal to what it was back in 1970, and kids should go outside alone, as they always did in human history. "If you try to prevent every possible danger or difficulty in your child's everyday life," she says, "that child never gets a chance to grow up."

Lenore Skenazy's Free-Range Kids sounds like a fascinating book (she has an accompanying blog too). Her argument, essentially, is that the crime rate today is equal to what it was back in 1970, and kids should go outside alone, as they always did in human history. "If you try to prevent every possible danger or difficulty in your child's everyday life," she says, "that child never gets a chance to grow up."

Our daughters have been walking to school by themselves for awhile now, but they're not wandering the neighbourhood all day as I used to 30 years ago. They probably should, but I don't think the idea has even occurred to them. That despite the likelihood that today's environment has probably made our kids safer than any kids have ever been, particularly when you take disease prevention into account.

In Vancouver, though, we can blame this new parental paranoia on Clifford Olson, and it has spread across much of the Western world. I think Skenazy's instinct to let her nine-year-old son explore New York City alone last April—with a transit pass and some quarters for a pay phone if he needed them (he didn't)—is a good one. He wanted to try, and he was ready.

"We become so bent out of shape over something as simple as letting your children out of sight on the playground that it starts seeming on par with letting them play on the railroad tracks at night. In the rain. In dark non-reflective coats," writes Skenazy. "The problem with this everything-is-dangerous outlook is that over-protectiveness is a danger in and of itself. A child who thinks he can't do anything on his own eventually can't."

Our experience bears this out, in an odd way. The only injuries my daughters have ever suffered that required hospital visits happened, (a) stepping out of our bathtub, (b) bouncing on a bed, (c) being rear-ended in a crash in our car, and (d) scraping a chin at a swimming pool. In all cases, we were right there, and we didn't make them any safer. There are dangers in all of our lives, but they're not generally the ones we fear.

Labels: controversy, family, linkbait, news, newyork, probability

09 April 2009

The terrorists you read, hear, and view

Buzz Bishop has a good point: if you measure the effectiveness of terrorism by the fear it generates and the behaviours it changes—the goals of terrorist organizations, after all—then the biggest terrorists are the news media. We humans, as usual, suck at evaluating risks, so TV, paper, and radio news often take advantage of us because of that.

Labels: controversy, fear, news, probability, security, terrorism

14 March 2008

Probability, the Fab Four, and my kids

As always, there are some people who think those darned kids today are taking us all to hell in a handbasket with their ignorance and filthy habits. However, I seem to recall titles like this only in my university statistics course textbook:

But that's not where it comes from. It's a school math worksheet for my younger daughter, who is eight and in grade two. I'm not sure "data management and probability" were words I could even say at that age. (Then again, I did know what "carbon monoxide" was from my first favourite book.)

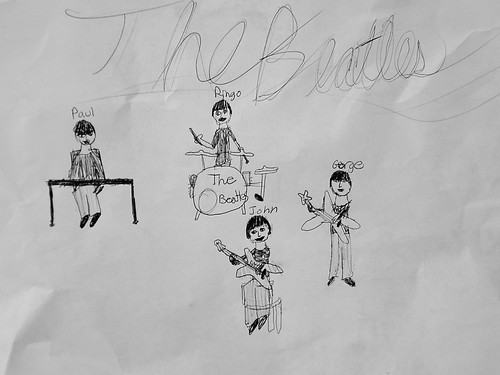

As for my other daughter, who is ten, she drew a picture the other day. It's taped to her bedroom door:

I liked the Beatles at that age too, but she loves them. I had no idea who the individual Beatles were, never mind what instruments they played—especially that Paul played piano as well as bass.

Notice that while John and George are playing their guitars left-handed, which isn't correct, Ringo's drums are frighteningly accurate. And even though his kit didn't have one, hers has a soundhole in the front drum head as most do these days. I guess my work as a drummer has rubbed off a bit.

Kids today. Too damned smart.

Labels: age, band, family, neurotics, probability, school

21 October 2007

Immunity and treatment, and coffins for children

It will soon be flu vaccine season again. Most parents in Canada have their kids vaccinated not only against flu, but also against a variety of other diseases. That's what governments and school boards and medical bodies recommend, and I agree with them—my wife and I have our kids immunized. As someone with diabetes and now cancer, I also get a flu shot every year, and have received vaccines against viral pneumonia and other pathogens.

I've written before about that, and about how links between MMR vaccines and autism don't seem supported by the evidence. There are other worries, but I think the common panel of immunizations has more benefits than risks. Measles, mumps, rubella, polio, and other diseases are nasty. Some of them often crippled and killed people.

Dr. Tara Smith has a good blog post on vaccines and other treatments not only for historically prevalent viral diseases, but also newer ones like AIDS. "People simply don't remember the havoc vaccine-preventable diseases used to wreak," she writes, "[which is] an attitude that leads to apathy. [T]he best public health is invisible—preventing disease rather than responding to outbreaks, so it's difficult for the average individual to realize how important it is until it's broken."

She's talking about AIDS (even though it has no vaccine yet), which here in the West has gone from death sentence to controllable condition in only a quarter century. In much of the rest of the world, it is still an unimaginable scourge, even while child mortality from other causes declines. First here in the industrialized world, and how slowly elsewhere, hygiene, better diets, and modern medicine have ameliorated conditions that routinely killed children and adults for almost the entire multi-million year history of our species.

One of the biggest changes in the past century is that parents can now reasonably expect to see all their children reach adulthood. Let me repeat: that wasn't true before. Routine childhood deaths were something Florence Nightingale, Charles Dickens, King Kamehameha, Isaac Newton, Queen Elizabeth I, Charlemagne, Genghis Khan, Acamapichtli of the Aztecs, William the Conqueror, Cleopatra, Julus Caesar, the Buddha, the Kings of Nubia, and Lucy the australopithecus shared with one another—and we do not. Here's an example.

In the early days of photography, people had to hold still for minutes at a time for portraits, like mannequins. (No wonder there were so few smiles. Or maybe that was the dental care.) Anyway, young children, as today, didn't tend to sit still, so those kids who did appear in family photos were frequently dead ones. It was the only way to get photos of them. And there was no shortage. They died, for the most part, from bacterial diseases treated today with antibiotics, viral infections now prevented by vaccines, and infections now controlled by better hygiene, nutrition, and general health.

Yes, we may be subjecting our kids to environmental toxins and other mysterious things that cause rising rates of asthma and allergies, and other conditions that are either more common to our more artificial world, or that were previously masked by all the sickness and death we now avoid. Yes, infant cold medicines probably don't work. But let's not forget that children simply are not sickened, maimed, and killed at anything remotely resembling the rates they used to be, in ways our parents and grandparents still remember.

And yes, there are newer vaccines like Gardasil for which the preventative benefits are still being established (heavy advertising by manufacturer Merck does promote caution in my mind). Less drastically, while chickenpox is rarely fatal, being immunized against it can also prevent the appearance of the much nastier condition shingles later in life. It is the same virus, re-emerging from decades of dormancy in the body.

Perhaps we need to improve the way and timing with which we administer treatments to our kids and ourselves, to get more benefit and reduce what risks they are. My wife and I are still going to get our shots this year (unless my oncologist recommends against it for me), and so are my daughters. Be smart and cautious with the treatments you give your own family.

But don't avoid modern medical preventions and treatments altogether. We cannot write off the biggest gift that science has given us over the last hundred years: making it an ever-shrinking, niche industry to build coffins for children.

Labels: cancer, controversy, death, diabetes, family, probability, science

18 October 2007

Choices vs. guesses

More than five years ago I linked to an argument by Canadian conservative newspaper columnist Andrew Coyne favouring action on climate change. His argument, essentially, was that:

...the chances that the many distinguished scientists who predict an impending climatological catastrophe will prove to be right must be considerably greater than the chances I will be run over by a bus tomorrow. Or at any rate, they are greater than zero. In which case, would it not be prudent to take out some insurance against the event?

And that the costs of emissions reductions and alternative energy strategies are not (or at least, were not in 2002) out of line with what you would expect to pay for insurance on similar potential risks.

My cousin recently sent me a simple nine-minute YouTube video on climate change risks (not really the "most terrifying video you'll ever see," but hey). It makes a similar point, perhaps more clearly, or at least more visually, with nothing but a guy at a whiteboard:

It comes down to choices vs. guesses: we can choose to change our energy use and effects on the planet's climate, or we can guess that we don't really need to do that. The risk of guessing is much bigger than the risk of choosing.

Labels: controversy, environment, probability, science

27 June 2007

Let's put it this way

The big picture has not changed since yesterday, but we're moving on. Raging torrents of information continue to flood in from the medical staff. I had an ultrasound probe and met with my surgeon Dr. Phang today. My operation is currently tentatively scheduled for July 13.

It is possible that, in the long run (whatever that means under my current circumstances), I may yet regain some use of my anal sphincter, rather than needing a permanent colostomy bag, but I'll have a temporary one no matter what. It is also possible that one of my kidneys might need to be removed, or maybe my ureter (which has cancer stuck to it) will just be shortened. Those things are the new ideas to me today, although neither is either guaranteed or impossible. So maybe, maybe not. I see a urologist next Tuesday about the kidney thing.

There's a lot of that right now. Maybe, maybe not.

Maybe the guy who just started his lawnmower outside at 8:15 bloody p.m. on a Wednesday night will come to his senses and shut it off. Or maybe not.

Maybe the surgery and future chemotherapy and other treatments will put the cancer cells at bay and I will live another few decades. Or maybe not.

There's a strange clarity in not knowing for sure. We all live that way, I guess, I'm just more directly aware of it than most of you. In many people's lives—and mine too—there are risks. Risks of car crashes and flesh-eating bacteria and falls in the bathtub and deployments to Afghanistan and mountain-climbing accidents and earthquakes and tsunamis and accidental electrocution and choking on chicken bones. And aggressive cancer.

These bodies of ours are fragile things, and amazing things. Here's to keeping my jalopy running for awhile yet.

Labels: cancer, colostomy, probability, surgery

19 May 2007

Feeling safe vs. being safe

Via netdud, I read once again another highly sensible article from Bruce Schneier about how badly we as a society usually react to security threats. It's a strange contrast to, and yet also a perfect demonstration of, my post yesterday about the Air India bombing, where it seems that direct, credible, likely threats didn't receive the attention they deserved—while today we confiscate nail clippers and remove shoes at airport security in a way that is likely totally ineffective.

I've written repeatedly about this stuff over the years here on my blog: about how our African savannah brains are poorly equipped to deal with the risks we face in the modern world.

But in another essay, Schneier also makes the point that "security theatre," as he terms it, isn't always wasteful, because sometimes it makes our perception of our security more closely match the statistical reality. That is rare—most of the time it throws money away and skews our perceptions further from reality—but we do also have to take into account how safe we feel, as well as how safe we are.

Labels: biology, evolution, probability, psychology, security, terrorism