Penmachine

09 April 2010

What does it mean to be old?

New Scientist has published a widely-linked article (via Kottke) this week called "The Shock of the Old," about how the world's population is aging. Author Fred Pearce is perhaps a bit too optimistic about what that means, but it's nevertheless a worthwhile read. It reinforces something I've written about before. As Pearce puts it:

We should be proud that for the first time most children reach adulthood and most adults grow old.

But old doesn't mean what it used to. I regularly hear news reports about an "elderly" person of age 70. But that's how old my parents are, and they don't seem at all elderly to me. Yes, my mom retired some years ago, but that doesn't seem to have slowed her down. My dad is still running his own business and driving to service calls almost every day. He'll happily climb a ladder to the roof of the house to clear out the gutters.

And of course, these days they're both in better shape than I am, at age 40.

I think societies like Canada's, where our population is aging rapidly, will have to adjust, to support people based not on the number of years they've lived, but on the capabilities they have. In some ways, we already do that—I'm receiving Canada Pension disability benefits, for instance. I don't know what that adjustment will look like, and I may not even live long enough to see the change, but it's coming.

Labels: age, canada, death, history, magazines, work

12 February 2010

Doing it right

Tonight's Winter Olympics opening ceremony was impressive, if often a bit phallic. There was one technical glitch with the hydraulics for the first, indoor cauldron in B.C. Place Stadium, but the ceremony did the most important thing right.

Tonight's Winter Olympics opening ceremony was impressive, if often a bit phallic. There was one technical glitch with the hydraulics for the first, indoor cauldron in B.C. Place Stadium, but the ceremony did the most important thing right.

That was to remember Nodar Kumaritashvili, who died this morning in a terrifying crash during a training run on the Whistler luge track, at the age of 21. (He was born the year the Winter Olympics were last in Canada, in Calgary in 1988.) He was the fourth athlete to die during a sporting event at the Winter Games since they began in 1924.

Jacques Rogge, the head of the International Olympic Committee, pre-empted his prepared remarks with a memorial to Kumaritashvili. Vancouver head organizer John Furlong also included the late athlete in his speech. There was a minute of silence during the ceremony, and a standing ovation for the remaining members of the small Georgian team, walking sadly wearing black armbands.

And the bonus? Instead of the rumoured Celine Dion, we got a spectacular k.d. lang. Good choice.

Labels: death, music, olympics, sports, television, vancouver

11 February 2010

One down

Three years ago, I set a couple of goals: to try to beat back cancer long enough to see the Winter Olympics come to Vancouver, and to live a couple of years longer so I could renew my driver's license when it expires in 2012.

Well, I hit the first one:

That's the Olympic torch being carried up Willingdon Avenue, about four blocks from my house, on its way through Burnaby and Vancouver to the opening ceremony tomorrow. Two years and a bit from now, maybe I'll get that new driver's license too.

Labels: cancer, death, driving, olympics

10 February 2010

Four eyes

Every few years, I get new glasses, not because my prescription has changed (it's been pretty stable for about a decade), but because my old spectacles simply get old and worn out. This year, I took advantage of a two-for-one sale and got one set of new plastic frames (centre below) and one set of metal ones (right):

They're not a big change from my old set (left), but I like the new looks, though I'm not sure which of the two I prefer. Back in 2008 when I bought my last set, I wasn't sure I'd survive long enough to need new ones, but here I am. Yay.

Which pair do you prefer?

Labels: cancer, death, ego, glasses

02 February 2010

So long, Blogger.com: I need a new blogging platform to publish static files

For close to a decade, since October 2000, I've published this home page using Blogger, the online publishing platform now owned by Google. That entire time, I've used the original hacky kludge created by Blogger's founders back in 1999, where I write my posts at the blogger.com website, but it then sends the resulting text files over the Internet to a web server I rent, using the venerable FTP (File Transfer Protocol) standard—which was itself last formally updated in 1985. This is known as Blogger FTP publishing.

For close to a decade, since October 2000, I've published this home page using Blogger, the online publishing platform now owned by Google. That entire time, I've used the original hacky kludge created by Blogger's founders back in 1999, where I write my posts at the blogger.com website, but it then sends the resulting text files over the Internet to a web server I rent, using the venerable FTP (File Transfer Protocol) standard—which was itself last formally updated in 1985. This is known as Blogger FTP publishing.

While often unreliable for various technical reasons, Blogger FTP works effectively for me, with my 13 years of accumulated stuff on this website. But I am in a small, small minority of Blogger users (under 0.5%, says Google). Almost everyone now:

- Uses Blogger's own servers for their sites.

- Or another hosted service that takes care of everything for them.

- Or if they want to publish on their own servers, another tool like Movable Type, WordPress, or ExpressionEngine, which you install on your server and publish from there.

So, as I've been expecting for years, Blogger is now permanently turning off FTP publishing, as of late March 2010. And, in my particular case, that means I need to find a new blog publishing tool within the next month or so.

This has been coming for a long time

Blogger has all sorts of clever solutions and resources for people using FTP publishing who want to migrate to Google's more modern server infrastructure, but they don't fit for me. I have specific and very personal needs and weird proclivities about how I want to run this website, and putting my blog on Google's servers simply doesn't meet them.

That's sad, and a little frustrating, but I'm not angry about it—and I think it's misguided that many people commenting on this topic seem to be. I realize that I have been getting an amazing, easy publishing service for free for almost a quarter of my life from Blogger. It has enriched my interactions with thousands of people. Again, for free. (Actually, I did pay for Blogger Pro back in the day before the 2003 Google acquisition, but that was brief. And as thanks, Google sent me a free Blogger hoodie afterwards—I still wear that.)

The vast, vast, vast majority of users find the newer ways of publishing with Blogger meet their needs. And any of us who has used FTP publishing for years knows it's flaky and convoluted and something of a pain in the butt, and always has been since Ev and his team cobbled it together. I've been happily surprised that Blogger has supported it for so long—again, free.

Yes, it was a distinguishing feature of Blogger that you could use a fully hosted editing and publishing system to post to a web server where you don't have to install anything yourself. Very nice, but I think there are good technical reasons that no other service, free or paid—whether WordPress.com, TypePad, SquareSpace, or anything else—ever offered something similar.

I applaud the Blogger team for trying to do the best they can for us oddballs. And it serves as a reminder: Blogger FTP can go away. Gmail could go away. Facebook could go away. Flickr could go away. Twitter could go away. WordPress.com could go away. If you're building your life or business around free online tools, you need some sort of Plan B.

I've had this possibility on my mind at least since the Google takeover, seven years ago. Now I have to act on it. But I'm thankful for a decade of generally great and reliable free service from Blogger. I haven't had ten free years of anything like it from any other company (online or in the real world), as far as I know.

Getting nothing but static

One other thing I've always liked about Blogger's FTP publishing is that it creates static files: plain-text files (with file extensions like .html or .php or .css, or even no extensions at all). It generates those files from a database on Google's servers, but once they're published to my website, they're just text, which web browsers interpret as HTML (Hypertext Markup Language) to create the formatting and colours as such.

Most other blogging tools, including Blogger's hosted services, generate their web pages on the fly from a database. That's often more convenient for a whole bunch of reasons, and I'm happy to run other sites, such as Inside Home Recording and Lip Gloss and Laptops, with a database-dependent tool such as WordPress.

But this site is my personal one—the archive of most of my writing over the past 25% of my life. And I'm a writer and editor by trade. This website is my thing, and I've worked fairly hard to keep it alive and functional, without breaking incoming links from other sites, for well over a decade now. I've always wanted to keep it running with static files, which is one reason I didn't migrate from Blogger to WordPress four or five years ago. Over on Facebook, Gillian asked me why I'm so hardheaded about it. (She's a database administrator by trade.)

I'll be blunt about the most extreme case: I have cancer. I may not live that long. But I'd like my website to stay, even if only so my kids can look at it later. If necessary, if I'm dead, I want someone to be able to zip up the directory structure of my blog, move it to a new server, unzip it, and there it is, live on the Web. I don't want to have to plan for future database administration in my will.

In that worst case I won't need to update my site anymore, but I think static files on a generic web server are more reliable in the long run. To make a bulk change, a simple search-and-replace can update the text files, for example, to note that it's not worth emailing me, since, being dead, I'll be unable to answer.

On other blogging and content management systems I've worked with, I've had MySQL databases die or get corrupted. Restoring from MySQL backups is a pain for non-techies, or even for me. I've blown up a WordPress site by mis-editing one part of one file, and I've been able to fix it—but I don't want someone else to have to do that.

Right now, if Blogger died entirely, my site would still work exactly as-is. If my web host went belly-up, anyone with a teeny bit of web savvy and access to my passwords and one of my computers could redirect penmachine.com to a new server, upload the contents of one of my backup directories to it by FTP, and (other than visitors being able to post new comments) it would be up and live just like it was within a day or two.

In addition, tools like WordPress are brittle. I like using them, but there are security updates all the time, so the software goes out of date. That's fine if you're maintaining your site all the time, but if not, it becomes vulnerable to hacks. So if a database-driven site choogles on without updates, it's liable to get compromised, and be defaced or destroyed. That's less likely with a bunch of HTML files in directories—or at least I think so.

Betting on text

Plain text has been the language of computer interchange for decades. If the Web ever stops supporting plain text files containing HTML, we'll all have big problems. But I don't think that will happen. The first web page ever made still works, and I hope and expect it will continue to. My oldest pages here are mild derivatives from pages that are only five years younger than that one. They still work, and I hope and expect that they will continue to.

At worst, even a relatively non-technical person can take a directory dump backup of my current website and open the pages in a text editor. I can do that with files I've had since before the Web existed—I still have copies on my hard drive of nonsensical stories from BBSes I posted to in the '80s (here's an HTML conversion I made of one of them). I wrote those stories with my friends, some of whom are now dead, but I can still read what we wrote together.

Those old text files, copies of words I wrote before some of the readers of this blog were born, still work, and I hope and expect they will continue to. Yeah, maybe a SQL backup would be wise, but I'll still place my bets on plain text. Okay, I'm weird, but there you go.

Suggestions

Okay, so I need a new blogging platform. Probably one I can install on my server, but definitely one that generates static files that don't depend on a live database. Movable Type does that. ExpressionEngine might. More obscure options, like Bloxsom and nanoc, do so in slightly more obscure ways.

If you know of others I should look at, please email me or leave a comment. However long I'm around, I'll remain nostalgic about and thankful to Blogger. It's been a good run.

Labels: blog, death, geekery, history, linkbait, memories, software, web, writing

05 January 2010

Death, pessimism, and realism

I've mused about death often enough on these blog pages, especially since I developed cancer in 2006 and it spread into my lungs since 2007, and now that it's gotten worse. I've also discussed my atheism and how that affects my attitude about death.

Some people think that without any belief in an afterlife, or a soul, or Heaven, death for me must be a scarier or emptier than for those who believe in such things—that somehow I must face death without comfort or solace. But that's not true. I have tried to explain it before, but yesterday blogger Greta Christina did a better job. She calls it "the difference between pessimism and realism," and it's worth a read, whatever you believe.

Labels: cancer, controversy, death, religion

27 November 2009

Oh fuck

I found out yesterday that there are new cancer tumours in the centre of my chest—several of them, each 2 to 3 cm in size, near where my lungs meet. They showed up on the CT scan I had Monday, and they were not there on the scan in September. That means they've grown quickly, which is fucking bad news.

After meeting with my doctors at the B.C. Cancer Agency yesterday, I've stopped using cediranib, the drug that had kept my existing lung tumours growing only very slowly over the past year. I'll likely return to more conventional and aggressive chemotherapy again sometime in the next couple of weeks.

Since I found out about my cancer almost three years ago, it has never been in remission. Some people who read this blog or know me in person have, mistakenly, thought otherwise, because I've often appeared in good health.

But my cancer has never shrunk, only slowed down. It started in my large intestine, then spread to my lungs from there. The bowel tumours came out with surgery in 2007—otherwise I would probably have died later that year. But the lung metastases can't really be tackled with surgery or radiation, because there are too many, too widely spread, and too deep in my body. Chemo is the best option.

This is serious. Faster-growing metastatic tumours near my lungs, my heart, my trachea, and my esophagus are dangerous and potentially lethal. In addition to attacking them with chemo, in a few months there may be some clinical trials of MEK inhibitor drugs available to me, but that's not certain. Those experimental medications operate on the kinase cascade metabolic pathway that helps cancer cells grow. So we'll see about those too.

New, fast-growing cancer is not what anyone wants in my body, but I can't say it's unexpected, or a genuine surprise. This is how cancer often goes. Treatments work, sometimes better, sometimes worse—and then sometimes they stop working. It's always a fight, and one I might lose.

My wife and children and parents and family and friends are sad. My head is swimming with thoughts of all sorts. Time to walk into the unknown future again.

Labels: cancer, chemotherapy, death, family, fear, friends, pain

18 November 2009

My interview last week on CBC TV

Last week, reporter Theresa Lalonde from CBC interviewed me at my house about how people can plan for what to do with their online presence after they die. The TV video report is now online, and soon I'll post the audio radio versions she did as well.

The topic is similar to a much longer interview I had with Nora Young at CBC's "Spark" last year. There are basically two components to the whole enterprise: figuring out which online activities of yours to shut down and how, and figuring out which ones to keep going and how.

Labels: cancer, cbc, death, radio, television, video

11 November 2009

Death and idealism

I have heard there was a time when some of the older veterans at today's Remembrance Day ceremonies thought there might be no more wars. They fought, and died, and killed, and saw the waste and destruction—and believed that perhaps the cost was too great. That nations and societies could decide to put the barbarism behind us.

There were young veterans at the ceremonies today, much younger than me, returned from Afghanistan and elsewhere. Sadly, I don't think they can share in that old idealism.

Labels: death, history, holiday, remembranceday, war

03 November 2009

Scary stuff, kiddies

For a long time (maybe a couple of years now), I've been having an on-and-off discussion with a friend via Facebook about God and atheism, evolution and intelligent design, and similar topics. He's a committed Christian, just as I'm a convinced atheist. While neither of us has changed the other's mind, the exchange has certainly got each of us thinking.

For a long time (maybe a couple of years now), I've been having an on-and-off discussion with a friend via Facebook about God and atheism, evolution and intelligent design, and similar topics. He's a committed Christian, just as I'm a convinced atheist. While neither of us has changed the other's mind, the exchange has certainly got each of us thinking.

Something that came up for me yesterday when I was writing to him was a question I sort of asked myself: what elements of current scientific knowledge make me uncomfortable? I try not to be someone who rejects ideas solely because they contradict my philosophy. I don't, for instance, think that there are Things We Are Not Meant to Know. However, like anyone, I'm more likely to enjoy a teardown of things I disagree with. Similarly, there are things that seem to be true that part of me hopes are not.

Don't be afraid of the dark

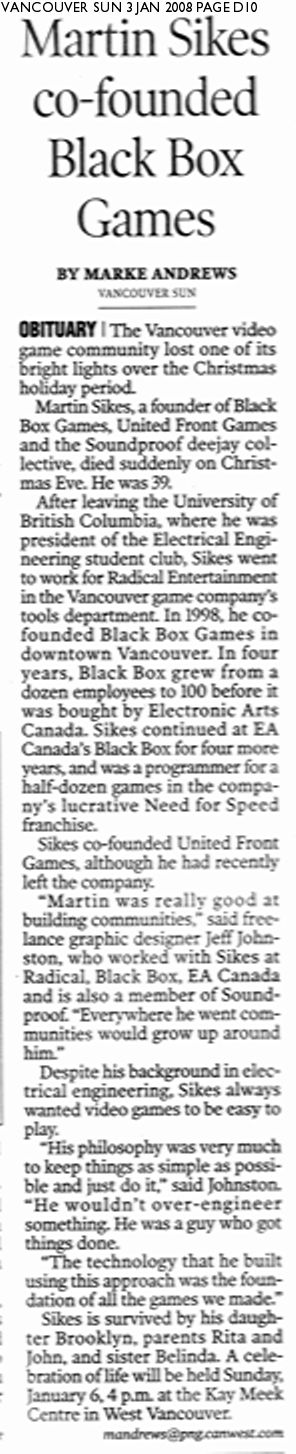

Recent discoveries in astrophysics and cosmology are a good example. Over the past couple of decades, improved observations of the distant universe have turned up a lot of evidence for dark matter and (more recently) dark energy. Those are so-far hypothetical constructs physicists have developed to explain why, for instance, galaxies rotate the way they do and the universe looks to be expanding faster than it should be. No one knows what dark matter and dark energy might actually be—they're not like any matter or energy we understand today.

But we can measure them, and they make up the vast majority of the gravitational influence visible in the universe—96% of it. So the kinds of matter and energy we're familiar with seem to compose only 4% of what exists. The rest is so bizarre that Nova host and physicist Neil deGrasse Tyson has said:

We call it dark energy but we could just as easily have called it Fred. The same is true of dark matter; 85 percent of all the gravity we measure in the universe is traceable to a substance about which we know nothing. We can call that Wilma, right? So one day we'll know what Fred and Wilma are but right now we measure the distance and those are the placeholder terms we give them.

We've been here before. Observations about the speed of light in the late 1800s contradicted some of the fundamental ideas about absolute space and time in Newtonian physics. Analysis yielded a set of new and different theories about space, time, and gravity in the early years of the 20th century. The guy who figured most of it out was Albert Einstein with his theories of relativity. It took a few more years for experiment and observation to confirm his ideas. Other theorists extended the implications into relativity's sister field of quantum mechanics—although there are still ways that general relativity and quantum mechanics don't quite square up with each other.

And if that seems obscure, keep in mind how much of the technology of our modern world—from lasers, transistors, and digital computers to GPS satellite systems and the Web you're reading this on—wouldn't work if relativity and quantum mechanics weren't true. Indeed, the very chemistry of our bodies depends on the quantum behaviour of electrons in the molecules that make us up. Modern physics has strange implications for causality and the nature of time, which make many people uncomfortable. But there's no rule that reality has to be comfortable.

Bummer, man

To the extent that I understand them, I've come to accept the fuzzy, probabilistic nature of reality at quantum scales, and the bent nature of spacetime at relativistic ones. Dark matter and energy are even pretty cool as concepts: most of the composition of the universe is still something we have only learned the very first things about.

But dark energy in particular still gives me the heebie-jeebies. That's because the reason physicists think it exists is that the universe is not only expanding, but expanding faster all the time. Dark energy, whatever it is, is pushing the universe apart.

Which means that, billions of years from now, that expansion won't slow down or reverse, as I learned it might when I was a kid watching Carl Sagan on Cosmos. Rather, it seems inevitable that, trillions of years from now, galaxies will spread so far apart that they are no longer detectable to each other, and then the stars will die, and then the black holes will evaporate, and the universe will enter a permanent state of heat death. (For a detailed description, the later chapters of Phil Plait's Death From the Skies! do a great job.)

To understate it rather profoundly, that seems like a bummer. I wish it weren't so. Sure, it's irrelevant to any of us, or to any life that has ever existed or will ever exist on any time scale we can understand. But to know that the universe is finite, with a definite end where entropy wins, bothers me. But as I said, reality has no reason to be comforting.

Either dark energy and dark matter are real, or current theories of cosmology and physics more generally are deeply, deeply wrong. Most likely the theories are largely right, if incomplete; dark matter and energy are real; and we will eventually determine what they are. There's a bit of comfort in that.

Labels: astronomy, death, science, time

06 September 2009

Les Paul's legacy

A few weeks ago I wrote about Les Paul, who died in mid-August at the age of 94. My podcast co-host Dave Chick and I decided that our next episode of Inside Home Recording would be a Les Paul special edition, dedicated to different aspects of Les's career, because as the inventor of multitracking and pioneer of solidbody electric guitars, he was so important to modern recording.

A few weeks ago I wrote about Les Paul, who died in mid-August at the age of 94. My podcast co-host Dave Chick and I decided that our next episode of Inside Home Recording would be a Les Paul special edition, dedicated to different aspects of Les's career, because as the inventor of multitracking and pioneer of solidbody electric guitars, he was so important to modern recording.

Tonight, we put that tribute episode (IHR #74, available as an enhanced AAC or audio-only MP3 podcast) online. In the process of putting it together, both Dave and I were astonished by how much Les Paul accomplished that we didn't even know about—most of it before we or any of our listeners were born.

I came to the conclusion, expressed in the our editorial at the end of the show, that Les was the single most important person in the history of modern recorded music—more important, on balance, than Thomas Edison or Leo Fender or Elvis or the Beatles or any of the other contenders.

You can listen to the show to find out if you agree. But it's indisputable that anywhere in the world where there is a microphone or a speaker, a Record button or a set of headphones—from every music studio or TV soundstage to every car stereo or iPod earbud, from every crummy punk dive bar to every high-end hip-hop nightclub, from the Amundsen-Scott outpost at the South Pole to the International Space Station—Les Paul played a part in making them what they are.

Labels: death, guitar, history, insidehomerecording, jazz, music, recording

30 August 2009

Old man, look at my life

I've come to realize something in the last few days. My cancer treatment drags on, keeping me alive but not really getting me better. I continue to manage my diabetes and live with an artificial IV port in my chest. I take lots of pills and shots, get medical tests, and see doctors all the time. I can't safely travel very far.

I've come to realize something in the last few days. My cancer treatment drags on, keeping me alive but not really getting me better. I continue to manage my diabetes and live with an artificial IV port in my chest. I take lots of pills and shots, get medical tests, and see doctors all the time. I can't safely travel very far.

More to the point, I hurt, and I'm tired. Many parts of my body simply don't work the way they're supposed to. Most of the time, I'm nothing close to genuinely well. I may never return to my great job. I've been like this in some form or another for more than two and a half years.

So here's what I realized. I'm a 40-year-old man whose body has become much older. I'm a youngish guy in an oldish container. There are plenty of people three decades beyond my age—including my own parents—who feel better than I do, and can do more. And the hard part (for all of us) is knowing there's a good chance they'll live longer than me too.

For the vast majority of human history, living to age 40 was an achievement in itself. Even a hundred years ago, Type 1 diabetes like I have was a death sentence too—I would have died in my early 20s, before I had a chance to marry my wonderful wife or have two great children. I'm glad I've had those chances.

If I were (for instance) 75 years old now, it would be easier to accept what cancer has done to me, and to acknowledge that living (for example) another five years would be a pretty good achievement. I'm trying to think more like that—not to be fatalistic, but to be pragmatic, to know that while I'll keep fighting, without radical new treatments or some very good luck, it's probably a losing battle. But that's not a failure.

I'm sitting on the back porch in the sun, drinking a coffee. In a few minutes I'll help my kids make some cake. It's a good life.

Labels: age, cancer, death, diabetes, family, navarik, pain

13 August 2009

Thank you, Les Paul

Cross-posted from Inside Home Recording...

No one who performs popular music, or records music of any kind, hasn't been affected by Les Paul, the legendary guitarist, musical innovator, and inventor who died today at age 94.

No one who performs popular music, or records music of any kind, hasn't been affected by Les Paul, the legendary guitarist, musical innovator, and inventor who died today at age 94.

Many people know him only for the solidbody electric guitar that bears his name—indeed, he hand-built his own solidbody electric years before that, but Gibson was uninterested in the design until rival Fender successfully sold similar concepts in the early 1950s. Still, Paul was not only a talented and prolific player (who continued a regular live gig in New York until very recently), but also a hit-making jazz and pop artist, as well as the inventor of multitrack recording and overdubbing, as well as tape delay and various phasing effects:

He was a constant tinkerer, heavily modifying even his own Les Paul guitars with customized electronics and switching, and often acting as his own producer, engineer, and tape operator. Every listener to Inside Home Recording, and every musician or recording enthusiast today, owes him a massive debt, and we'll all miss his talent and contributions.

Labels: death, insidehomerecording, jazz, music, recording

19 February 2009

A bit of a shock

Our friend Kim is one of the designers competing on this season's Project Runway Canada, so we've been watching the show since it started a few weeks ago. It was filmed last summer in Ottawa. At the end of this Tuesday's episode, I was shocked to see an announcement that one of the designers, Danio Frangella (who left during the first episode because of health complications) died last week of cancer. He was 34.

Our friend Kim is one of the designers competing on this season's Project Runway Canada, so we've been watching the show since it started a few weeks ago. It was filmed last summer in Ottawa. At the end of this Tuesday's episode, I was shocked to see an announcement that one of the designers, Danio Frangella (who left during the first episode because of health complications) died last week of cancer. He was 34.

He was not in good shape during that first episode, because he'd been undergoing cancer treatment for seven years, and had trouble walking because of his leg ulcers. Learning that he had died gave me a chill, because of course I have cancer too, and have had it for a couple of years now. Indeed, this week it is exactly two years since I began my medical leave from work. Two years!

If you haven't had cancer or known someone with it, you tend to assume that once someone gets it, they either get treated and go into remission (or are cured), or they die pretty swiftly. Those aren't the only alternatives. Many people live with the disease for years, sometimes decades, undergoing treatments and adjusting their lives around their symptoms and side effects. Danio was one of those, and so am I.

Even successful treatments may not be what you expect. Most statistical studies look at cancer treatments as successful if their subjects are still alive after five years—you often see "five-year survival rates" in such studies. I suppose that's fine if you're a researcher, or if you're a cancer patient in your 70s or 80s.

But if you're not yet 40, like me, or like Danio, five years isn't a very long time. I have a decent chance of surviving five years past my diagnosis, but that's not enormously encouraging, not when most people my age are thinking ahead a lot more than five years. I'm already almost half-way to the five-year mark. All the medications I've taken since 2007 haven't done what they really need to do, which is stop or reverse the nine small metastatic tumours still growing (slowly) in my lungs. On the other hand, I've also already lived longer than a lot of people diagnosed with my sort of aggressive colon cancer do.

One of the first things my gastroenterologist Dr. Enns told me back in '07 is that while there are tons of statistics out there on cancer survival rates, no one person is such a number, and the statistics can't predict how one person's disease will progress, or how long they will live. Just yesterday my oncologist Dr. Kim noted that research shows physicians to be notoriously poor at predicting life expectancy for cancer patients—no better than patients do ourselves, and in many cases no better than a wild guess.

As I wrote recently, I have "months certainly, years quite possibly" to live. How many years, I don't know. Nobody knows. Will I see my kids graduate from high school, or reach my 20th wedding anniversary with my wife in 2015? It's possible, but unless a new treatment starts working, or I go into remission because of lifestyle changes or another reason in that time, it may not be likely.

Then again, some people die young in car crashes or for other reasons, never anticipating their last day, or their last minute. If I'd been born 100 years ago, I would probably have died in my early 20s from diabetes, and might never have married or had children, or even seen a website, let alone built one like this. And if I lived in Swaziland (where 38% of adults have AIDS) or Afghanistan (with astronomical rates of infant mortality), even today, I'd be at the end of the average male life expectancy already.

Here, I am lucky to have a wonderful family, and support, and great health care, and I can still choose to live, to enjoy it, to write what you read, and to make my life as long and happy as I can.

Labels: cancer, chemotherapy, death, diabetes, family, television

25 December 2008

A Christmas toast to Martin and James

It's been a busy Christmas, made busier by enough snow to nearly paralyze a usually not-very-snowy city like Vancouver. Yet my wife, daughters, and I were able to pilot our snow-tire-equipped Toyota Echo through the wilds of East Vancouver to my aunt and uncle's house for our traditional family Christmas Eve event. We did have to bunk out there overnight, though.

It's been a busy Christmas, made busier by enough snow to nearly paralyze a usually not-very-snowy city like Vancouver. Yet my wife, daughters, and I were able to pilot our snow-tire-equipped Toyota Echo through the wilds of East Vancouver to my aunt and uncle's house for our traditional family Christmas Eve event. We did have to bunk out there overnight, though.

Today, Christmas Day, we made it home, cleaned up, changed, unpacked, and then ventured out to Maple Ridge for a quiet dinner with my wife's parents. The roads by then were better. Besides eating, I performed some of the usual in-laws' tech support to help my father-in-law configure their new Internet Wi-Fi radio set, and my mother-in-law create her first blog. (No content yet, so a link must wait.) With more snow forecast, we made an early night of it and returned to Burnaby again, and Christmas was complete.

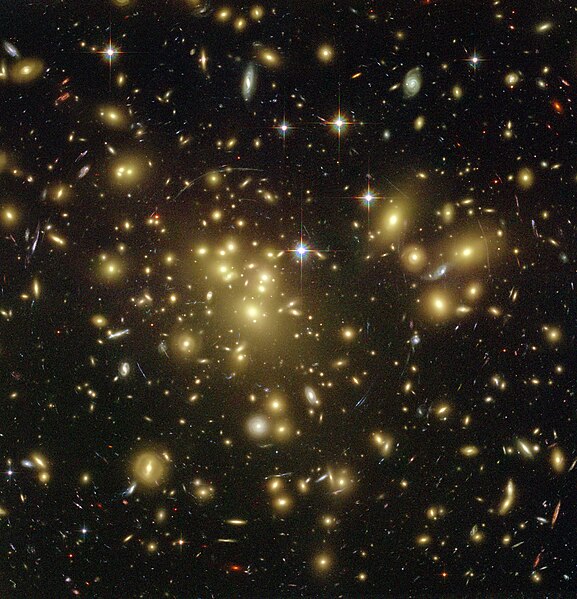

Now, as the day ends, I think back not only on Christmas and my happiness at being relatively healthy again this year (tumours in my lungs are still growing, but very slowly, and maybe my new holistic health approach is assisting the cediranib in keeping them somewhat at bay), but also about the deaths of two people. They were my friend Martin Sikes, who died suddenly a year ago on the morning of Christmas Eve, after sending me what turned out to be a spooky email; and James Brown, who appropriately, somehow chose the most bombastic of days, December 25, to make his last fleet-footed shuffle off the stage.

From now on, to me, December 24 will also be Martin Day, and December 25 is JB Day. In their honour, I'm drinking my first glass of The Balvenie 15-year-old scotch whisky tonight, from a bottle given to me on my birthday in 2007 by Alistair—but which I have only now opened.

I hear the plow truck finally making a pass through our street outside, near midnight. I am exhausted, and content. Slàinte to MS and JB, and Merry Christmas to you.

Labels: cancer, chemotherapy, death, driving, holiday, inspirehealth, martinsikes, music, vancouver, weather

21 November 2008

Farewell, Mr. PJ

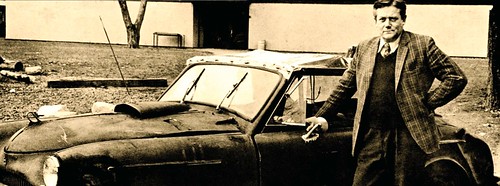

In 1986 I was in the last class of Math 12 students taught by Tony Parker-Jervis, the legendary mathematics teacher, hot-rod enthusiast, and curmudgeon at St. George's School. He had been on staff there since the '50s or early '60s—and before that, he had been among the school's first students, graduating in 1935 before going off to war, where he taught himself advanced mathematics while calculating ballistics trajectories.

In 1986 I was in the last class of Math 12 students taught by Tony Parker-Jervis, the legendary mathematics teacher, hot-rod enthusiast, and curmudgeon at St. George's School. He had been on staff there since the '50s or early '60s—and before that, he had been among the school's first students, graduating in 1935 before going off to war, where he taught himself advanced mathematics while calculating ballistics trajectories.

I just received a message that Mr. PJ has died, more than two decades after he retired. Former students like me remember him fondly, though he terrified us at the time. His ruthless high standards and eccentric teaching and testing methods are probably the main reason that I, not a natural mathematician, scored well enough in provincial exams and Euclid contests to take advanced-level freshman math courses at university. (I finally exhausted my capabilities with the brain-bending black art of integral calculus, where I squeaked by with 56%.)

It strikes me as odd now, but seemed natural at a British-style boys' school in the '80s: Mr. PJ spoke with a distinct, growly English accent. That's strange because he grew up here in Vancouver. He also smoked relentlessly, wore chalk-stained tweed jackets (or maybe the same jacket?) every day, and was infamous for keeping underperforming students after school for short tests he made up on the spot. He called them GOWYGIAR—Get Out When You Get It All Right. We pupils could help each other as he sat at his desk or paced the room threateningly, but each of us could only leave when we had answered every question to his satisfaction. Sometimes they were long afternoons.

UPDATE: His British accent is more sensible now that I know that in addition to being born in Singapore and spending his first few years on a Malaysian rubber plantation (which I had heard before), he studied in England after living in Vancouver, before the War (which I had not). The new details are from his obituary, published in the Vancouver Sun.

Our raw marks in his classes were pitiful, because his tests and assignments were so hard that all but the most gifted boys routinely averaged 30 or 40%. But he scaled up our scores by some inscrutable formula that usually bumped the best marks—maybe as high as 70%!—up to 100%, dragging the rest of us along. He chuckled wryly at that, but he taught us enough that provincial exams seemed easy.

Mr. PJ drove a massive '70s Cadillac, but his secret weapon was an old Austin (British car, of course) that he had souped up himself with a huge V8 engine and bizarre silver paint. Rumours had it capable of well over 150 miles an hour. I'm not sure what he did to the Austin frame to keep it from annihilating itself at such speeds. He no longer brought it to school regularly when I was there, but we did see it occasionally. It merited its own three-page spread in The Dragon (PDF), the school newsletter, as late as last year. The article was simply called "THE CAR," and we all knew what it was talking about.

I hadn't seen or heard from Mr. PJ at all in the past 22 years, and don't even know what he'd been up to. Like other teachers who have died since I left St. George's School, including my old home room teacher Craig Newell this year, he leaves a gap that I didn't realize was there. The influence of teachers, decades later, is remarkable.

Labels: death, memories, school, teaching, vancouver

11 November 2008

Soggy fields on a sombre day

It's miserable, sloppy, rainy November day here in Vancouver. It often is on Remembrance Day, and that's appropriate. Soldiers die on all sorts of days—sunny, rainy, snowy, windy, or calm—but this weather fits the mood.

It's miserable, sloppy, rainy November day here in Vancouver. It often is on Remembrance Day, and that's appropriate. Soldiers die on all sorts of days—sunny, rainy, snowy, windy, or calm—but this weather fits the mood.

We used to know it as Armistice Day, to commemorate the end of World War I, which we used to know as the Great War. But the holiday has once more come to have greater meaning in recent years, as our soldiers die in distant wars again. It's no longer a remembrance of history alone—the veterans and their families are no longer exclusively old. Sure, I fight my own battle with cancer, and with death, but when I see the names and faces of Canadians killed in Afghanistan, and think of Afghans dying there too, I consider how young many of them are, just as their predecessors were overwhelmingly young.

Most are much younger than me, never having had a chance to age or get ill. Just gone early, from bullets or bombs, gas or grenades.

Today isn't a glorious day, but a sombre one. Our yards and cemeteries are puddled and muddy, like those battlefields so regularly were—and are. That helps me remember.

Labels: death, holiday, remembranceday, vancouver, war, weather

25 October 2008

The living part

I think some of you might have garnered the wrong impression from my previous entry. I'm not giving up on conventional cancer treatment, nor am I resigned to dying soon. Rather, I'm considering my choices more carefully, trying some new things, and making a stronger cost-benefit analysis of the options presented to me.

I think some of you might have garnered the wrong impression from my previous entry. I'm not giving up on conventional cancer treatment, nor am I resigned to dying soon. Rather, I'm considering my choices more carefully, trying some new things, and making a stronger cost-benefit analysis of the options presented to me.

Until September, the conventional treatments I'd been taking—chemotherapy, radiation, surgery—still showed reasonable promise of putting my cancer into remission, or shrinking it, or even (before we knew it had metastasized into my lungs) curing it. So it was worth trying everything, side effects and life-on-hold be damned. The surgery worked its magic: if the cancer cells hadn't found their way to my lungs first, I might very well be cancer-free by now from the skilled work of Dr. Phang and his team at St. Paul's Hospital. The radiation I'd had before that might even have helped.

But the chemo...well, those various poisons I've taken in 2007 and 2008 may very well have kept any further cancer from appearing in my intestines, but the tumours in my lungs are tough little fuckers, and have resisted being beaten down. Now I have to look at the new treatments I might have coming up, and decide whether their relatively low likelihood of zapping those same malfunctioning blobs of tissue are worth what I might have to suffer in taking them.

I mean, it's fine and noble to help cancer research, but I've already done that a couple of times. I might still do it this time, but even if I do, I'm prepared to bail out early if the side effects are too harsh or if it doesn't seem to be helping. I'm also meeting with a doctor at Inspire Health next Friday to talk about other stuff: nutrition, exercise, relaxation, complementary treatments, and so on.

This is a new phase of how I understand my disease, and how my family and I live with it, one I feel good about because I'm putting a priority on the living part.

Labels: cancer, chemotherapy, death, family, inspirehealth, science, surgery

23 October 2008

To fight, or to live

My wife Air is wiser than me—more self-aware, better at thinking long term. A big reason I'm not that way is because, until I developed cancer at the beginning of last year, I'd never had to face big, difficult decisions. I had a happy, stable childhood, did well in school, lucked into good jobs, and found her. (More accurately, she found me. See what I mean?)

My wife Air is wiser than me—more self-aware, better at thinking long term. A big reason I'm not that way is because, until I developed cancer at the beginning of last year, I'd never had to face big, difficult decisions. I had a happy, stable childhood, did well in school, lucked into good jobs, and found her. (More accurately, she found me. See what I mean?)

Even after my cancer diagnosis, I've followed the path I've usually chosen in life. That is, I've coasted, and let gravity take me where it will. My treatment decisions have been easy ones. Follow doctors' orders. Get tests, have surgery, take chemotherapy and radiation, more tests, more surgery, more chemo, more chemicals, more treatments, coming up on two years' worth now.

On hold

The surgeries in my intestines were successful, but small nodules of cancer spread to my lungs anyway, and the chemical medicines for those haven't worked so well. The metastases continue to grow slowly, regardless of what my doctors have thrown at them.

My latest surgery a couple of weeks ago was my first that wasn't about attacking the cancer. It was simply to make my life better, to reconnect my intestines so that I'm no longer walking around with an ileostomy bag of poop glued to my belly. Now I have another new, healing scar, and I'm re-learning how to use the bathroom the way I used to.

That surgery prompted my wife to have a talk with me a couple of days ago. With her wisdom, and her insight, she's seen what I've been doing in my mind for the past couple of years. I've been treating my cancer as something to fight with everything the doctors and nurses can offer, no matter how sick they make me, hoping that one of those weapons will kill it so I can move on with my life. I've put my life on hold—and my family's life too, hers and our daughters'—to fight the disease, treating it as a phase to get through before I return to something normal.

Experiment, not treatment

Except that's not how it's going. The next treatment the B.C. Cancer Agency is offering me is a Phase I clinical trial of chemotherapy agents. That means it's a very early human test of the drugs involved, not even designed to find out whether the drugs work to fight cancer, but rather how patients like me respond to them—what levels they appear at in my bloodstream, how they interact, what side effects they produce. In other words, we've run out of the conventional therapies, and we're moving on to experimental ones that have a very small chance of working. They are, however, likely to produce side effects, even if they aren't effective in shrinking my cancer.

Air made me ask myself—after almost two years on hold, most of which I've spent hammered down by those side effects, or recovering from surgery—how I want to live my life with cancer. Because that's what it looks like I'll have to do. We don't know how long that will be: months certainly, years quite possibly. All indications are that, like my diabetes, I'll have cancer for the rest of my life. It will probably be what kills me, whenever that is.

Yet since I stopped my last chemo treatments in September, I've felt good, verging on healthy, better than I have in ages. Therefore, much of what I've suffered through, especially recently, has been from the treatments, not from the disease. I thought that suffering was a necessary part of the fight. So I thought. But now it's time to make some real decisions.

Real decisions

Do I want to be part of this new Phase I trial, to contribute semi-altruistically to cancer research, spending many days at the Cancer Agency getting tests, taking pills every day, maybe feeling sick all the time and getting more strange skin rashes, perhaps even developing other weird side effects like elevated blood pressure, maybe for no reason that might actually get me better?

Or do I want to look at something else, like Vancouver's Inspire Health Integrated Cancer Care, and the Callanish Retreats, to try different things and look at managing cancer instead of fighting it? Strange as it sounds, should I make cancer part of how I live my life, rather than something that stops me from living it?

When I heard about the trial yesterday, I assumed, almost unconsciously, that I'd proceed with it. But that's still coasting, just taking whatever the doctors serve up from a diminishing buffet. There are places I still want to go in my life, things I want to do, the husband and father I still want to be. Perhaps now is the time to go there, to do them, to be that, because I can't wait forever first.

I shouldn't waste my life trying win a fight that likely can't be won. I should take it off hold, and live it.

Labels: cancer, chemotherapy, death, family, ileostomy, inspirehealth, love, science, surgery, travel

17 October 2008

Links of interest (2008-10-17):

Sorry, I'm not keeping very good track of my sources for these:

- Eighty-four variations of the iconic Obama "HOPE" poster.

- "...incentive plans based on measuring performance always backfire. Not sometimes. Always."

- "If I have grown more cynical in recent years, it is travel, I think, that has pushed me in this direction. Exploring other parts of the world is beneficial in all the ways it is typically given credit for [...] But traveling can also burn you out, suck away your faith in humanity. You will see, right there in front of you, how the world is falling to pieces."

- A $15 USB controller shaped like the classic Atari 2600 joystick.

- Fabulous video of the recent SpaceX launch—the first successful commercial orbital rocket launch ever. If you're interested, here's a Google Maps satellite photo of the launch facility in the South Pacific, midway between Hawaii and New Guinea.

- Why we can't imagine what it's like to be dead.

- Blues guitar legend Robert Johnson died 70 years ago. Someone might have recently discovered a new photograph of him, one of at most a handful existing.

Labels: death, gadgets, linksofinterest, money, music, photography, politics, space, travel

11 September 2008

Chemo is suddenly over again, for now

So, how do I put this? The chemotherapy isn't working (at least, not well enough), so my doctors have cancelled it and we're looking for something else to keep the cancer from progressing. That may include different, more experimental forms of chemo, or surgical radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of the spots in my lungs. In my initial reading, the RFA approach looks like it could be promising.

My emotions about this development are all over the place. To know that the largest metastatic lesion in my lungs has grown from 1.4 cm to 1.6 cm in diameter, and the smaller one from 1 cm to 1.4 cm, is dismaying, because the panitumumab and irinotecan I was taking weren't doing the job of stopping or shrinking those tumours. On the other hand, I may have been misinformed about there being four metastases; there might be only two. I'm not sure and will have to ask. They are small, and not growing extremely fast.

In addition to that, now I can avoid spending two days in bed every two weeks, feeling like I'm going to throw up. My pervasive dry skin and facial rash, although under control, should now abate as the chemo drugs flush out of my system. Finally, since it will take a few weeks to figure out and schedule my next treatments, whatever they are, I'm taking the chance to try to have my ileostomy surgically reversed, so that my intestines function normally again for the first time in well over a year and I can ditch the colostomy bags forever. That could happen in less than a month.

We found all this out a couple of days ago, which happened to be my wife Air's 40th birthday. Fortunately, we'd already had a big family-and-friends barbecue last weekend to celebrate that (plus my mom's upcoming 70th), so the news only dampered the day itself, not the party. Last night she and I went for dinner at the beautiful Horizons restaurant here in Burnaby, to mark her birthday and to celebrate at least the end of chemo, for now.

This all reminds me that while my medical team and I keep looking for a cure, something to destroy the cancer completely, more likely we're just buying me time. How much time, no one knows. Months? Years? Right now, other than the dry skin, I feel better than I have at any time since my diagnosis in January 2007. I feel less like a dead man walking than ever, but the future remains a mystery.

Yet on September 11, another dreadful anniversary, the weather here in Vancouver is once again beautiful, and there's laundry to be done. Time to load up the iPod and get to it.

Labels: anniversary, birthday, cancer, chemotherapy, death, pain, surgery

03 September 2008

I'd like to cry more

I haven't cried for awhile. Back when doctors first found my cancer, more than a year and half ago, I cried frequently. Later in the year, after I'd been through chemo and radiation and surgery and catastrophic weight loss and side effects, I would sometimes wake in the night and sob in my wife's arms, "I don't want to die."

I haven't cried for awhile. Back when doctors first found my cancer, more than a year and half ago, I cried frequently. Later in the year, after I'd been through chemo and radiation and surgery and catastrophic weight loss and side effects, I would sometimes wake in the night and sob in my wife's arms, "I don't want to die."

I still don't, and I still have cancer. I'm still taking chemotherapy every two weeks, lying in bed for a couple of days and throwing up. But it has become a grinding routine, a long, protracted war against my body's own mutant cells, rather than a fierce battle.

I wish I cried more. I'm not holding it back. When it comes, crying is a great relief. I feel alive.

But I think I'm a bit numb to the threat of death now—I could still die soon, but it seems less likely, since my medical team and I seem to be fighting the disease decently, and I feel pretty well most of the time. My family and I talk about the future, and such talk no longer seems hollow.

I also laugh, especially with my kids, and my wife, and my band. I played another show with them this afternoon, and one thing I enjoy best about it is that pretty much every show, I laugh uncontrollably at least once about something.

It's true that I'm more sentimental now, and get misty-eyed at times when I might previously have been stoic or cynical. Sometimes it's just when I look at my daughters. Sometimes it's when I see pictures from Mars. Sometimes it's when I'm writing a blog post.

Labels: band, cancer, death, family, music

03 May 2008

Another eulogy

Tomorrow, for the second time this year, I'll be giving a speech at a memorial service. This time it's for my mom's oldest friend Sonia, who died last November. She would have turned 70 in January.

I had no trouble at all putting together a eulogy for my friend Martin in January, but this time around it's a bit more difficult. My relationship with Sonia was different—she was my mother's friend, after all, so every time I saw her it was related to something they were doing together—but also lifelong. By the time I was born in 1969, they had been friends for well over 20 years.

Sonia's three best friends (my mom included) compiled some information and stories for me to work with, and I have some ideas on how to turn them into a speech, but I feel already like there will be too much left out. It's hard to distill 60 years of friendship into five or six minutes, maybe one minute for each decade. And the group at the memorial will be much smaller than Martin's, maybe 50 or 60 people instead of several hundred. I actually find it easier to speak in front of large groups than small.

Anyway, I'll find the key things to talk about, plus some extras I know myself, and I think it will go just fine. I hope I can do Sonia and her friends justice.

I feel a little guilty about one thing: I'm sort of glad to make speeches like this. That's because each memorial I attend means I've made it long enough not to have my own.

Labels: death, family, friends

18 March 2008

Farewell to Sir Arthur

While I have to admit that his fiction was sometimes a bit wooden, Sir Arthur C. Clarke, who died today, was one of the true visionaries of the last century. Geostationary telecommunications satellites—the ones we all use now for all sorts of things—were his idea. He helped with the deployment of radar in World War II. And in novels like Rendezvous With Rama and Childhood's End, he imagined how humans might react if we find out we aren't alone in the universe.

In many ways, he helped build the frame around our modern ideas about astronomy, cosmology, and space travel. He was no doubt disappointed that we didn't pursue the kind of space program started in the 1950s and '60s. We're certainly far from the routine orbital and lunar trips he and Stanley Kubrick forecasted in 2001.

He was, in many ways, an eccentric, married only once, briefly, decades ago, and spending the last 50 years of his life in Sri Lanka after leaving his native Britain. He was also a master of pithy quotes: "Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic." "If there are any gods whose chief concern is man, they cannot be very important gods." "Any teacher that can be replaced by a machine should be!" "There is hopeful symbolism in the fact that flags do not wave in a vacuum." "I don't believe in astrology; I'm a Sagittarian and we're sceptical."

I read a lot of his stuff when I was young, and he is one reason I turned into a geek and a science major. He lived a long life, to 90, but it's still a sad day that he's gone.

Labels: age, arthurcclarke, astronomy, books, death, science, sciencefiction

04 March 2008

Braveblogging

Many months ago I said, about my cancer treatment, that I'm not brave, even though people say it. Bravery is facing danger head-on when you have other choices. Here have been my choices over the past year and a bit:

- Potentially life-saving small surgery? Yes or no?

- Potentially life-saving two-month radiation treatment? Yes or no?

- Potentially life-saving early two-month chemotherapy? Yes or no?

- Potentially life-saving large surgery? Yes or no?

- Potentially life-saving late six-month chemotherapy? Yes or no?

The basic choice has been: Treatment or death? Yes or no?

That's a pretty easy decision.

My real choices have been pretty small, and the choice to blog (and appear on the radio) about all this stuff was also an easy one, because this was the question: Write about my cancer like I write about everything else, and keep the information flowing? Or live two lives, and try to remember whom I've told and whom I should be hiding stuff from every single damn day?

Why would I choose to keep it private? Given who I am, how could I possibly do that and stay focused?

I said in that radio interview and elsewhere that, as far as relating to other people goes, cancer is an easy disease. People don't judge me for it. (Perhaps if it wasn't colorectal cancer, but lung cancer from smoking or liver cancer from drinking, some people might judge me. But even so, cancer is no longer "the C word.") They're sympathetic, and cut me a lot of slack.

What takes some bravery is what fellow Vancouver blogger Corinna is doing at her site Gus Greeper: writing in painful, wrenching detail about her depression, anxiety, and therapy. And her trip to the hospital yesterday after she downed a handful of pills and some wine.

Depression and other mental illnesses still have a big stigma. They shouldn't. For someone who has never experienced them, like me, they are tremendously difficult to understand, but that doesn't make them less real. And let me tell you, until you've been close to or had cancer yourself, you don't understand it either.

Stay brave, Corinna. It's worth the fight.

Labels: blog, cancer, chemotherapy, death, depression, radiation, radio, surgery

07 January 2008

Less who we were

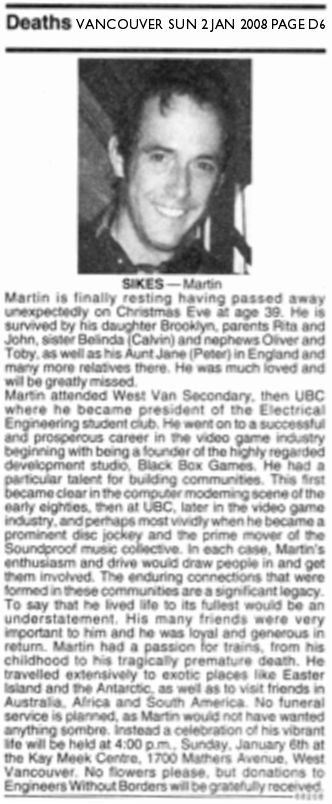

The profound shame about yesterday's memorial event for my late friend Martin Sikes is that many of us who spoke and sang and laughed and cried there didn't take the chance to tell him why he was important to us while he was still alive.

The profound shame about yesterday's memorial event for my late friend Martin Sikes is that many of us who spoke and sang and laughed and cried there didn't take the chance to tell him why he was important to us while he was still alive.

I was glad that I both spoke and played drums at the event—being busy helped distract me a bit so I didn't cry the whole time. I certainly had to clutch my wife's hand for support.

Martin was, by any measure, an extraordinary man. Otherwise there wouldn't have been 400 people—from relatives to co-workers to high school and university chums to those who only knew him from the parties he organized—out to remember him on a sleety January Sunday afternoon. More than one person told me they were quite surprised at how many different directions, into what they thought were completely unrelated groups of their acquaintances, they discovered his influence had reached.

Martin was, by any measure, an extraordinary man. Otherwise there wouldn't have been 400 people—from relatives to co-workers to high school and university chums to those who only knew him from the parties he organized—out to remember him on a sleety January Sunday afternoon. More than one person told me they were quite surprised at how many different directions, into what they thought were completely unrelated groups of their acquaintances, they discovered his influence had reached.

To find out why, you can take a look at the memorial page I set up for him, which also includes notes from several of the eulogies spoken in West Vancouver yesterday. I learned a lot about Martin from those talks, especially about his life as a kid before I knew him, and his career and pastimes over the past decade or so, when I saw him only sporadically.

To find out why, you can take a look at the memorial page I set up for him, which also includes notes from several of the eulogies spoken in West Vancouver yesterday. I learned a lot about Martin from those talks, especially about his life as a kid before I knew him, and his career and pastimes over the past decade or so, when I saw him only sporadically.

I expect some of his more recent friends and acquaintances might have learned stuff too. For example, his first commercial software success, the Blue Board software he sold as a teenager from his parents' house. Or that he, as a comfortably out gay man, had a girlfriend 20 years ago. (Any of them who'd ever met his adult daughter might have deduced that, of course.) My friend Sebastien summed Martin up best by saying that he was always trying not just to have fun, but to invent fun.

After the memorial, a bunch of Martin's old modemer Excursionist friends, including his daughter and her mom, gathered at Denny's on Burrard Street in downtown Vancouver, one of our frequent hangouts in the mid- and late 1980s. I think Martin's death hit us all harder than we might have expected. (I'm still bursting into tears at unpredictable moments today.) Like Dave wrote, we miss him more than we realized, for a panoply of reasons.

After the memorial, a bunch of Martin's old modemer Excursionist friends, including his daughter and her mom, gathered at Denny's on Burrard Street in downtown Vancouver, one of our frequent hangouts in the mid- and late 1980s. I think Martin's death hit us all harder than we might have expected. (I'm still bursting into tears at unpredictable moments today.) Like Dave wrote, we miss him more than we realized, for a panoply of reasons.

And we spoke of getting together more frequently too—some of us had not seen each other in 15 years or more. We figured out that the things we miss about Martin are also things we miss about each other. Teenage and early adult years are formative for anyone. But those of us who were part of Vancouver's early BBS community have an additional kinship of having been geeks before it was cool, and of having lived and loved and made friends (not to mention mistakes) online 10 or 20 years before the whole rest of the world started doing it.

I've said before that I have the technology and privacy instincts of a modern 17-year-old (search for me online, and you can find out almost anything you need to know, and probably more than you want). That's because when my friends and I were 17, we were already keeping in touch by flinging bits. However, perhaps uniquely, while we remember a time before email and the Internet, they were still critical components of how we grew up.

Many of us have remained in technical fields, yet have drifted in different directions. Still, when we do meet, the connection is immediate, and not merely nostalgic. At dinner, we still finished one another's sentences, even on topics (Facebook, climate change, the habits of our children) that didn't exist in our university days. After our greasy meal, I drove Larry, Bob, and Richard home across the eastern suburbs of Vancouver, and had tea at Richard's place before heading home myself. We spoke a bit about old times, but also nerded out about wireless data, servers, rebuilding houses, and fish tanks.

Many of us have remained in technical fields, yet have drifted in different directions. Still, when we do meet, the connection is immediate, and not merely nostalgic. At dinner, we still finished one another's sentences, even on topics (Facebook, climate change, the habits of our children) that didn't exist in our university days. After our greasy meal, I drove Larry, Bob, and Richard home across the eastern suburbs of Vancouver, and had tea at Richard's place before heading home myself. We spoke a bit about old times, but also nerded out about wireless data, servers, rebuilding houses, and fish tanks.

Who we were is also who we are. Martin was part of that, but he isn't anymore, which is one reason why losing him made us so sad. Despite his many successes, and much more than the rest of us, he had chosen to stay (or perhaps couldn't avoid remaining) the tinkering, pranking, inventing, train-obsessed, silly, party-throwing, risk-taking person he was when we were growing up together. Who we are can't be as much who we were without him.

Labels: bbs, death, friends, geekery, martinsikes, memories

05 January 2008

Martin Sikes memorial tomorrow 4 p.m.

Friends and relatives of Martin Sikes have organized a celebration of his life tomorrow, Sunday, January 6, at 4:00 p.m., at the Kay Meek Centre in West Vancouver. Here are a couple of articles about him from the Vancouver Sun this past week:

NOTE: I've now set up a memorial page for Martin, including links to articles about him, copies of the notes from his eulogy speakers, and photos from his memorial event on January 6, 2008.

Labels: bbs, death, friends, geekery, martinsikes, videogames

31 December 2007

Hell of a year

Some good things happened in my life in 2007. My kids took their first trip to Disneyland, and at the same time I made my first visit to the NAMM Show next door, which is like Disneyland for music geeks. I finally saw The Police in concert. My wife threw me a great birthday party. One of my best friends became pregnant with her first child, due in February 2008.

Some good things happened in my life in 2007. My kids took their first trip to Disneyland, and at the same time I made my first visit to the NAMM Show next door, which is like Disneyland for music geeks. I finally saw The Police in concert. My wife threw me a great birthday party. One of my best friends became pregnant with her first child, due in February 2008.

But otherwise it's been pretty rough. Back in January 2007, I first got my cancer diagnosis, and since then I've had four surgeries (one major), two rounds of chemotherapy (the second one is half-way over now), six weeks of daily radiation treatments, and almost a month in hospital, during which I dropped down more than 50 pounds below my normal weight.

To top it off, the year ended with the deaths of my mom's longtime friend, world figures Oscar Peterson and Benazir Bhutto, and my friend Martin, whom I'd known for more than 20 years. All role models, all flawed in their ways.

NOTE: I've now set up a memorial page for Martin, including links to articles about him, copies of the notes from his eulogy speakers, and photos from his memorial event on January 6, 2008.

And yet. And yet.

I have two very different yet wonderful daughters now approaching adolescence, and a wife who is by far my best friend and confidant. I have faced death and, so far, beaten it back. I have things I yet want to do, but also know that if I don't get to do them, I'm satisfied with what I've already accomplished in my life.

I'm glad to see 2007 gone, no doubt. I'm more optimistic now to see the end of 2008 than I was at some times during this past year. I'm surprisingly clear in how I see my place in the world. That's something of a gift.

Next Sunday there will be a memorial for Martin, who did not see the end of this year. I've been asked to speak briefly about his modeming and BBS days. One thing I know of him is that he was always trying to find new ways to have fun, and to be happy.

In my mind, we all have our lives and our families and friends, and we each must try to be happy, because they are all we have. Happy 2008 to you.

Labels: bbs, cancer, death, family, friends, geekery, holiday

27 December 2007

And so I cried

NOTE: I've now set up a memorial page for Martin, including links to articles about him, copies of the notes from his eulogy speakers, and photos from his memorial event on January 6, 2008.

I mentioned that yesterday, in the shock of hearing about the death of my friend Martin, I hadn't yet cried. That changed today, and what prompted my tears was something small that I'd seen earlier this week and forgotten about.

As I've done since 2003, just before Christmas on December 23, I had sent out a holiday e-card (a photo of my family) to several dozen of our friends, colleagues, and acquaintances. Martin was on the list. He had replied with a brief, somewhat mistyped Merry Christmas message and a mention of his upcoming planned New Year's party, sent from his BlackBerry.

The next day, long before I heard the news, I had read his reply among others from our friends, filed it away, and forgotten about it. Today, as the snow fell outside and I was deleting some of the bounced emails from defunct addresses on my e-card list, by chance I came across his message again. He'd sent it at 11:44 p.m. on the 23rd, and sometime between then and the time I first read and filed it on the 24th, he had died. It must have been one of the last messages he had sent. I went cold. It was like an email from a ghost.

That was too much, and I went into the bathroom and wept. I blew my nose. The tissue was bloody from the side effects of the chemotherapy that is keeping me alive. Not much later, I cried again on my wife's shoulder when I told her the story.

Tonight my daughters and wife and I had dinner with Simon, the friend who told me the bad news, on the lower slopes of the North Shore mountain where he and Martin and others had once shared a house—and where Martin had hosted my bachelor party in 1995, at the end of a night exploring empty storm drains under the City of West Vancouver. At dinner, Simon and my family and I drank a toast to our lost friend. We're still stunned, and we weren't sure what to say.

Since my post yesterday I've heard from several people to whom Martin was important. I realized that for many of us, he was a pivot in our lives, someone who, though he never reached age 40, affected the kinds of people his friends have become, and for the better. Perhaps that is what each of us should strive to do.

Labels: chemotherapy, death, family, friends

26 December 2007

Martin Sikes - 1968-2007

I've been wondering how to write this blog post all day, or whether to do it at all. But it seems silly (not to mention out of character) to avoid, so I'll just see what comes out.

I've been wondering how to write this blog post all day, or whether to do it at all. But it seems silly (not to mention out of character) to avoid, so I'll just see what comes out.

UPDATE: This post originally had "1970-2007" in the title, which was wrong. I knew that in my head (Martin was born before me, in 1968), yet his Facebook profile said differently, and I used that. Details are easy to screw up. I've corrected the title after a note from our friend Johan.

I've also now set up a memorial page for Martin, including links to articles about him, copies of the notes from his eulogy speakers, and photos from his memorial event on January 6, 2008.

I heard this morning via a phone call from my good friend Simon that one of our mutual friends, Martin, died early in the day on Christmas Eve. While I didn't see much of him these days, I had known Martin for more than 20 years, since our days as BBS geeks in the early 1980s. We first met in person at Vancouver's Expo 86, at least a couple of years after I'd met him virtually online. He showed up at Expo with a shock of blonde dyed into his dark hair, and a Super 8 film camera with which he was making strange little time-lapse movies of everything he saw.

I can't confirm what details I've heard about his death, so I'll avoid repeating them in case anything is incorrect. His last Facebook update, from a week ago, talked about the snow on one of our local ski hills, from which he'd just returned. So his death seems to have been quite accidental, and certainly unexpected. While over the years it has happened to a few people I've known who were roughly my age, Martin is the first friend of mine to die, as far as I can remember.

He was a talented engineer who had recently "retired" (in his mid-30s) after making a bunch of money when his video game company was bought out. He seems to have spent much of his time since then DJing and organizing raves and other events. Maybe he'd spent some time riding freight trains, at which he was also an expert. Both of his parents and his daughter, now a young adult herself, have survived him.

Years ago Martin and I used to take mountain-biking trips together in the backcountry around Greater Vancouver. Engineer that he was, he brought the topographic maps (this was pre-GPS), and he was always hard to keep up with. We traversed the logging roads between Squamish and Indian Arm. He witnessed my worst-ever case of road rash, where I took a downhill on a logging road too fast and ended up sliding down the gravel on my side.

I've thought a lot about death this year. Having stage 4 metastatic cancer will do that. What's particularly strange about it is that Martin hosted a party for me on in June at his fabulous condo high up in a Yaletown tower, a few weeks before the big surgery that put me in hospital for most of July, and from which it took me months more to recover.

Yet here I am, still kicking, feeling as good as I have in all of 2007 despite my ongoing chemotherapy, and Martin is suddenly gone.

I haven't cried yet, but I still may. I came close when I saw my youngest daughter sprawled out asleep in bed as if she'd fallen from the ceiling, and it reminded me of Martin's daughter doing the same at a party about two decades ago. Mostly I distracted myself in a lazy post-Christmas day with my family watching TV (including a whole slew more of MythBusters), and late tonight I've been listening to a bunch of blues, plus the amped-up blues that is the latest White Stripes album. Jack White's Ph.D.-level guitar distortion helps draw the sadness out and cauterize it a bit.

Part of me feels it slightly unseemly to write this, since I'm not sure it's what his family and closer friends would want. Yet I hope they don't mind, because not writing it wouldn't be right either, like a hole in this blog—always a very personal place for me—where something important should be.

I'm not one to speak or write to the dead, as many are doing on Martin's Facebook page. I don't think he's anywhere to hear me anymore. I'll simply say that, as little as I saw Martin in recent years, I miss him with his twinkly eyes and off-kilter funny techie stories. I know many other people who surely do too. Together our memories will preserve what was best about him.

Labels: bbs, cancer, death, friends, geekery, memories, music, vancouver

15 November 2007

Why 2007 continues to suck

Early yesterday morning, my mom's oldest friend died. Sonia met my mother when they were both in elementary school here in Vancouver, almost 60 years ago. By comparison, that's like my older daughter staying friends with one of her classmates until 2066. There was an autopsy today, but I haven't heard the results yet; we expect a heart attack, following Sonia's bypass surgery not long ago.

I knew Sonia my whole life, along with my mother's two other longtime friends, who have all continued to cook each other fancy dinners and share social events for over half a century. The four of them traveled through Europe for two years in the early sixties, and returned for a month-long reprise in 1981. Sonia was one of my mom's bridesmaids, and the two of them took belly-dancing lessons together in the seventies.

Like her friends, Sonia was an intelligent, independent, and individual woman. She traveled extensively around the world for many years, made and sold paintings, and lived in the same East Vancouver walkup apartment—a few blocks from the house I first lived in as an infant, and where my aunt and uncle live now—as long as I can remember. She never married or had children, and retired from her job with ICBC, our provincial auto insurance agency, several years ago.

Theoretically, hers was not a death in the family, but it's as close as you can get. I last saw her and her dark hair at our Thanksgiving dinner in October. I'll miss her at Christmas.

Labels: death, family, friends

11 November 2007

Graves

10 November 2007

Worth remembering

I went to St. George's School, a private boys' high school in Vancouver. It was founded in the early 1930s, so many of the school's first graduates fought in World War II. Quite a number of them died.

I went to St. George's School, a private boys' high school in Vancouver. It was founded in the early 1930s, so many of the school's first graduates fought in World War II. Quite a number of them died.