Penmachine

08 April 2010

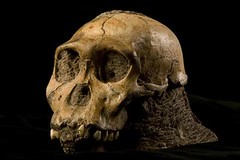

Another relative

It's quite astonishing how many fossils of extinct human relatives that paleontologists have found in recent years. Just in the past year, I've mentioned Darwinius and Ardipithecus. And this week we hear about Australopithecus sediba, which sheds further light on how ancient apes transitioned to walking upright like we do.

It's quite astonishing how many fossils of extinct human relatives that paleontologists have found in recent years. Just in the past year, I've mentioned Darwinius and Ardipithecus. And this week we hear about Australopithecus sediba, which sheds further light on how ancient apes transitioned to walking upright like we do.

It's a relief that in the latest coverage, the scientists involved have gone out of their way to say that A. sediba is not a "missing link":

"The 'missing link' made sense when we could take the earliest fossils and the latest ones and line them up in a row. It was easy back then," explained Smithsonian Institution paleontologist Richard Potts. But now researchers know there was great diversity of branches in the human family tree rather than a single smooth line.

All of evolution works that way: branching, somewhat messy relationships between organisms, with many extinct species and a few (or perhaps many) survivors. In the case of hominids, we humans are the only bipedal ones left, and we're also by far the most numerous of the surviving lineage, which includes chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans too. So our evolutionary past can look linear, at least during the past 5 to 7 million years since our ancestral line diverged from the chimp ancestral line, even though it wasn't.

While we have found quite a few fossils of human relatives, that's a very relative term. Until the past few thousand years, there weren't many of us around at all. All the Australopithecus fossils ever found can be outnumbered by the number of trilobite fossils (which are hundreds of millions of years older!) in a single chunk of stone at any rocks-and-gems store. Hominid fossils are still extremely rare things, so we can't reconstruct the branches of our family tree with perfect accuracy. That's because we can't be sure which (if any) of the species we've unearthed were our direct ancestors, and which were our "cousins"—branches of the tree that died out.

Still, we can make attempts with the data we have, some making more assumptions than others, and the options being quite complex. Yet as we find out more, and discover more, our family tree becomes clearer. That's pretty cool.

Labels: africa, evolution, history, science