Penmachine

03 November 2009

Scary stuff, kiddies

For a long time (maybe a couple of years now), I've been having an on-and-off discussion with a friend via Facebook about God and atheism, evolution and intelligent design, and similar topics. He's a committed Christian, just as I'm a convinced atheist. While neither of us has changed the other's mind, the exchange has certainly got each of us thinking.

For a long time (maybe a couple of years now), I've been having an on-and-off discussion with a friend via Facebook about God and atheism, evolution and intelligent design, and similar topics. He's a committed Christian, just as I'm a convinced atheist. While neither of us has changed the other's mind, the exchange has certainly got each of us thinking.

Something that came up for me yesterday when I was writing to him was a question I sort of asked myself: what elements of current scientific knowledge make me uncomfortable? I try not to be someone who rejects ideas solely because they contradict my philosophy. I don't, for instance, think that there are Things We Are Not Meant to Know. However, like anyone, I'm more likely to enjoy a teardown of things I disagree with. Similarly, there are things that seem to be true that part of me hopes are not.

Don't be afraid of the dark

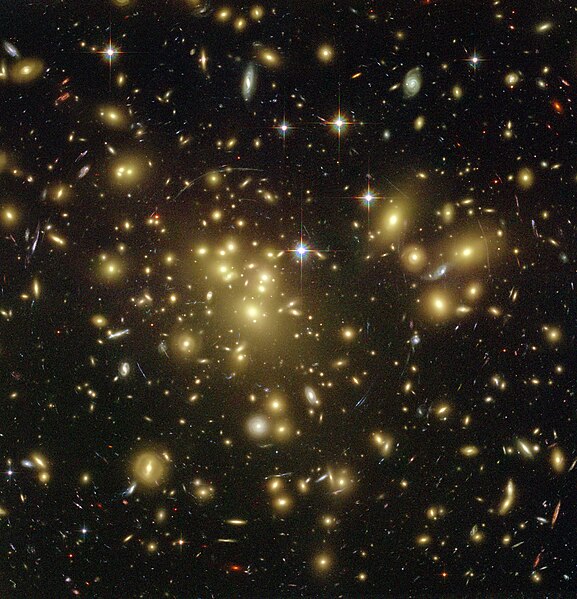

Recent discoveries in astrophysics and cosmology are a good example. Over the past couple of decades, improved observations of the distant universe have turned up a lot of evidence for dark matter and (more recently) dark energy. Those are so-far hypothetical constructs physicists have developed to explain why, for instance, galaxies rotate the way they do and the universe looks to be expanding faster than it should be. No one knows what dark matter and dark energy might actually be—they're not like any matter or energy we understand today.

But we can measure them, and they make up the vast majority of the gravitational influence visible in the universe—96% of it. So the kinds of matter and energy we're familiar with seem to compose only 4% of what exists. The rest is so bizarre that Nova host and physicist Neil deGrasse Tyson has said:

We call it dark energy but we could just as easily have called it Fred. The same is true of dark matter; 85 percent of all the gravity we measure in the universe is traceable to a substance about which we know nothing. We can call that Wilma, right? So one day we'll know what Fred and Wilma are but right now we measure the distance and those are the placeholder terms we give them.

We've been here before. Observations about the speed of light in the late 1800s contradicted some of the fundamental ideas about absolute space and time in Newtonian physics. Analysis yielded a set of new and different theories about space, time, and gravity in the early years of the 20th century. The guy who figured most of it out was Albert Einstein with his theories of relativity. It took a few more years for experiment and observation to confirm his ideas. Other theorists extended the implications into relativity's sister field of quantum mechanics—although there are still ways that general relativity and quantum mechanics don't quite square up with each other.

And if that seems obscure, keep in mind how much of the technology of our modern world—from lasers, transistors, and digital computers to GPS satellite systems and the Web you're reading this on—wouldn't work if relativity and quantum mechanics weren't true. Indeed, the very chemistry of our bodies depends on the quantum behaviour of electrons in the molecules that make us up. Modern physics has strange implications for causality and the nature of time, which make many people uncomfortable. But there's no rule that reality has to be comfortable.

Bummer, man

To the extent that I understand them, I've come to accept the fuzzy, probabilistic nature of reality at quantum scales, and the bent nature of spacetime at relativistic ones. Dark matter and energy are even pretty cool as concepts: most of the composition of the universe is still something we have only learned the very first things about.

But dark energy in particular still gives me the heebie-jeebies. That's because the reason physicists think it exists is that the universe is not only expanding, but expanding faster all the time. Dark energy, whatever it is, is pushing the universe apart.

Which means that, billions of years from now, that expansion won't slow down or reverse, as I learned it might when I was a kid watching Carl Sagan on Cosmos. Rather, it seems inevitable that, trillions of years from now, galaxies will spread so far apart that they are no longer detectable to each other, and then the stars will die, and then the black holes will evaporate, and the universe will enter a permanent state of heat death. (For a detailed description, the later chapters of Phil Plait's Death From the Skies! do a great job.)

To understate it rather profoundly, that seems like a bummer. I wish it weren't so. Sure, it's irrelevant to any of us, or to any life that has ever existed or will ever exist on any time scale we can understand. But to know that the universe is finite, with a definite end where entropy wins, bothers me. But as I said, reality has no reason to be comforting.

Either dark energy and dark matter are real, or current theories of cosmology and physics more generally are deeply, deeply wrong. Most likely the theories are largely right, if incomplete; dark matter and energy are real; and we will eventually determine what they are. There's a bit of comfort in that.

Labels: astronomy, death, science, time

Comments:

Anomaly #1: Most of the universe is missing.

The book is focused on describing the anomalies, but Brooks often wonders how many of these mysteries are actually Kuhnian paradigms on the cusp of a shift.

Thinking about infinity makes me dizzy.

But the gravity of nearer groups of galaxies is bending the light from those far-away ones, creating a gravitational lens that distorts that distant light, but also concentrating it so we can actually see it by the time it reaches us. The lensing confirms Einstein's theory of general relativity, and the amount of distortion is what indicates that dark matter is involved, because there's not nearly enough visible mass to cause the amount of lensing we're witnessing.

I think that's a whole lot cooler than the prosaic creation myths people have come up with over the millennia.

I love getting into philosophical debates with people convinced that there is a higher power out there. Like you, I respect their opinion, but it still makes me confirm that my feelings are still the same.

Science in itself makes me think, too.

And of course we humans, and even our descendants or relatives, will be long extinct before the heat death of the universe (which will occur after there's nothing but black holes left anyway). Our sun is already about half-way through its life, and its self-destruction is still five billion years or so away. No species has survived here beyond a few hundred million years anyway, and humans are latecomers already, only a few hundred thousand years old, depending on what you count as human.

So this is all a philosophical discussion: we and our descendants will all be annihilated well before the universe even changes significantly from how it is now.

Anyway, I find the immensity of the universe in time and space and the problems that it poses for human comprehension very interesting.

This didn't sit well with my Kurzweilian plans to first replace old or failing organs with cloned improvements, then become a brain in a jar, then a brain in a jar mounted in a giant robotosaurus, and continue along a sequence of upgrades until my consciousness is migrated to a communal, immortal databank. I didn't give this scenario a high probability, but it really disturbed me for a while that it truthfully had an absolute zero probability. This revealed to me that my Motive was founded on the assumption that I might theoretically create, initiate, or maybe just contribute to some process that would survive indefinitely. Without that foundation, it felt like we were exerting a lot of sweat just to build metaphorical sandcastles.

For me, it worked to adjust my motivational foundation away from any assumptions of permanence or objective morality, and strive purely for the endorphins that the body and brain I drive around in rewards me with. Selfish as that sounds, it works out in the wash because I find I am powerfully rewarded with these chemical Scooby Snacks when exercising altruism to those whose lives I can affect in the present. Beer does a reasonably good job too.

I don't pretend to understand it perfectly, being a layman, but its proponents say that it does away with the need for a period of rapid inflation, as well as providing a way for the math of the big bang(s) not to have to reduce to a singularity.

It still leaves me wondering about first causes though.