Penmachine

26 April 2009

Taking photos doesn't make you a terrorist

As far as I know, no actual or suspected terrorist has ever scoped out a potential target by walking around or in it in plain view, with a big camera and lens, and taking pictures. The 9/11 hijackers didn't, the U.S.S. Cole attackers didn't, the bombers of the London Underground and Madrid and Bali didn't. The FLQ kidnappers in 1970 didn't. Ahmed Rassam didn't. Suicide bombers in Israel and Iraq and Afghanistan don't.

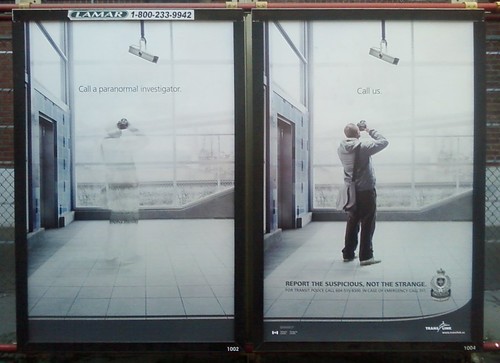

So ads like this one, postered at SkyTrain stations here in Vancouver as the 2010 Olympics approach, bother me:

The theme of the ad campaign is "report the suspicious, not the strange." It's an odd slogan. What's the difference between, "Hey, that's strange" and "Hey, that's suspicious"?

And the examples it gives are ridiculous. In this particular instance, if you see a camera floating in mid-air with a translucent, ghost-like figure beneath it, you should apparently call a paranormal investigator. But if you see a man with a DSLR taking photos of the security camera in the station, report that to the Transit Police, because he could be a bad guy.

Here's the thing. Taking photographs in public places isn't illegal in Canada. (Is a SkyTrain station a public place? Interesting question.) Neither is it illegal in the U.S., nor in Britain—though laws are more restrictive in the U.K.

A U.S.-based lawyer has put together a quick PDF card about photographers' rights, and it's also interesting to note that TransLink itself has responded to photographers' concerns about the campaign:

Specifically, the image of the photographer is not intended to say photography and photographers are bad. It's intended to say that a person who is intently making records of specific transit security elements like cameras should raise a flag as suspicious activity.

...but:

They're taking pictures of wiring, pipes, electrical panels. Well, I'm sorry, not many people go around doing that.

Really? Sure about that? Hmm?

The problem, of course, is that while TransLink staff and police may understand that intention (I hope!), the implication is that if members of the general public see a photographer taking pictures of something other than friends and family, they should be suspicious and report it. In short, that they should be afraid.

There's a more general message in these types of campaigns, and the way some reporters and photography enthusiasts are treated by authorities, too: that big cameras with big lenses are particularly evil, as this satire notes:

I don’t want to be too technical, but the focal length of the lens is directly correlated with hatred of America. It goes something like this:

You have a a cell phone camera, point and shoot, or 20mm wide angle lens: you are a red blooded American who wants to celebrate our national heritage by taking pictures of popular tourist locations.

A 50mm lens: you are also, by and large, a good American, but you have a disturbing interest in “understanding” the terrorists and why they attack us.

An 85mm lens: you loathe your own country and secretly admire the 9/11 hijackers for giving us our comeuppance. You are not a terrorist, but your camera should probably be confiscated and your pictures deleted, lest they find their way to al Jazeera message boards. Your middle name may be Hussein.

A 200mm lens: you are an al Qaeda henchman actively scouting for security vulnerabilities.

A 300mm lens: you ARE bin Laden!

This approach, of course, is the very opposite of sensible. If terrorists really were checking out a target, they would probably work to be as surreptitious as possible. Use small cameras, like the camera phone I used to photograph the ad poster. Memorize things and sketch them out later. Steal plans. Not plop down a big-ass tripod out in the open and carefully compose an image with a huge DSLR and a monster chunk of lens mounted it. At the very least, all that gear would make it hard to get away quickly and unobtrusively.

You know what I think has really prompted this security theatre? Spy movies and TV shows. That's where you see the telephoto lenses in the hands of the bad guys, and the good guys, for that matter. (Then again, James Bond prefers small cameras.)

What this approach fails to notice is that those are fiction.

Labels: controversy, olympics, photography, terrorism, transportation

Comments:

Wanna come along?

This reminds me of an anecdote from a friend who lived in the ex-Czechoslovakia, who spent some uncomfortable hours being interrogated because he took a photo of a freight train. "It looked interesting," was not a satisfactory answer - nobody takes pictures of trains unless they're up to no good.

Scott Bourne holds Rudi Giulliani responsible for the 'war on photographers' ... thankfully over here we haven't had too many zealous security guards .... yet!

Cheers

Steve Taylor (aka The_BigBlueCat)

Melbourne, Australia