Penmachine

16 August 2008

Camera Works: crop factors, 35 mm equivalents, and digital lenses

When you're shopping for digital cameras today, you'll see that they advertise lens focal lengths with numbers in "35 mm equivalent." Other specs might talk about a "crop factor" or "focal length multiplier" of 1.5 or 1.6 or 2.0 or more. What do those mean, and why didn't we hear about them back in the film days? Learning about 35 mm film will help us find out.

When you're shopping for digital cameras today, you'll see that they advertise lens focal lengths with numbers in "35 mm equivalent." Other specs might talk about a "crop factor" or "focal length multiplier" of 1.5 or 1.6 or 2.0 or more. What do those mean, and why didn't we hear about them back in the film days? Learning about 35 mm film will help us find out.

It's amazing how long 35 mm film (known as 135 film for still cameras) has been around. William Dickson, Thomas Edison, and George Eastman established its dimensions and specifications, right down to the distance between the sprocket holes, back in 1892—but that was for movie film. A number of still camera makers had the clever idea of using the same film stock for still pictures in the early 20th century, and it really took off among professional and enthusiast photographers in the 1920s, when Leica brought out its first tough little rangefinder cameras and excellent lenses.

NOTE: This article is now also available translated into Italian.

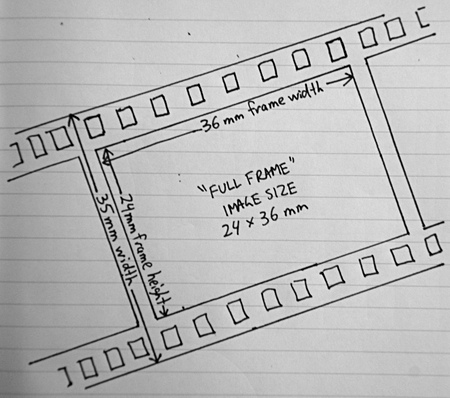

What is a full frame?

35 mm film gets its name honestly: the strips are 35 mm (about 1.4 inches) across, including the sprocket borders. In movie cameras it runs vertically, and the individual movie frames are 22 mm wide (leaving 13 mm for the margins and sprockets) by 16 mm high. But still cameras like the Leica M series (introduced in 1954) and Nikon F SLRs (first appearing in 1959) ran the film horizontally, as well as doubling the size of the image, making it 24 mm high by 36 mm wide. Today we call a film frame or digital sensor of that size "full frame."

Movie film was useful because it came in long rolls that could hold a lot of pictures, and it offered a good compromise between convenience, cost, and picture quality—especially compared to the sheet film and glass plates used by those big view cameras, where the photographer had to hide under a cloth and use bellows for focusing. The form of the standard 35 mm film roll cartridge was established pretty early too, which means that you can stick a brand-new roll of Fuji or Kodak film in a 50-year-old Leica. (And if you could find a well-preserved 50-year-old roll of film, it would fit in a new Canon film SLR too.)

The dominance of 135

Over the years many other film types came and went, from rolls for the popular Brownie in the '40s to small 120 cartridges for flashcube-equipped point-and-shoots from the '70s, disc film in the '80s, and Advanced Photo System (APS) rolls in the '90s. Polaroid did well with magical instant prints, and a big contingent of professionals has always used medium- and large-format film for extra high resolution in their Hasselblads and big studio cameras.

But nothing has lasted as long or been as ubiquitous and diverse as 135 film. You could get it as slide reversal film, colour or black-and-white print rolls, infrared strips, or super-sensitive cold-treated stock for telescope photography. Speeds ranged from super-slow but fine-grained Kodachrome to ultra-sensitive grainy print stocks for fast action and low light. You could buy 35 mm rolls anywhere from pharmacies in New York City to kiosks trailside in the Himalayas.

For 135 film, the 24 x 36 mm frame size never changed, so you could put pretty much any film roll in nearly any camera you could find, from a $200 autofocus pocketcam to a $2000 Nikon F4. And the lenses that camera makers created, whether the tiny plastic globule at the front of a single-use disposable cardboard camera or a $10,000 Canon L series super-telephoto, used focal lengths that made sense for that standard frame. "Normal" lenses had focal lengths in the 40 to 60 mm range. Wide-angle lenses had shorter focal lengths, and telephotos longer ones.

And then, around the turn of the 21st century, digital cameras started taking over. That threw everything into chaos.

Smaller sensors, smaller circles, smaller lenses

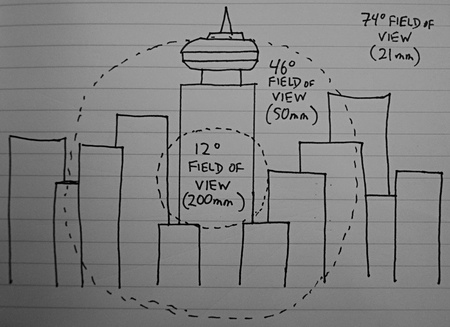

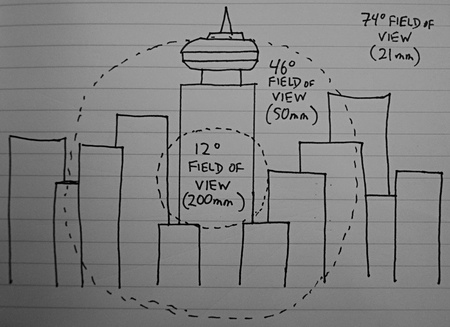

If you go back to my lens focal length article, you'll recall this diagram:

Fields of view for lenses of different focal lengths on a full-frame camera.

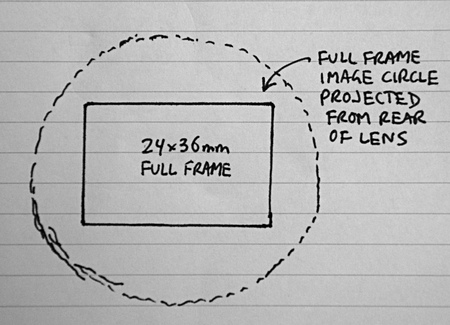

It shows the different fields of view from different lens focal lengths. When I first talked about that diagram, I discussed those angle-of-view circles as the cone of light that each lens "sucks in" from the front of the lens. But the whole point of the lens is that it not only sucks in that light, but projects it out the back too, onto the focal plane at the rear of your camera. That's where the projected image circle falls on the film or digital sensor when the shutter is open.

For most of the past century, lenses for SLRs and other 35 mm cameras were optimized to project a circle of roughly the same size, to cover the full 24 x 36 mm film frame behind the shutter:

That means that a full-frame image circle has to be at least 43.3 mm in diameter, because that's the diagonal width of the full film frame. Whether you're talking about a 500 mm telephoto, a 24 mm wide angle, or even an 8 mm fisheye or 70-200 mm zoom, whatever angle of view they're sucking in, they have to project a circle 43.3 mm across onto the film plane. (Actually, it's usually a bit wider, just to avoid the inevitable light falloff at the edges of lenses.)

Most digital cameras, however, are different. Until a few years ago, it was prohibitively expensive to produce a full-frame digital sensor, and it's still a lot costlier than making something smaller. As recently as 2003, the cheapest full-frame camera you could buy was a $5000 Kodak digital SLR, and that was a big price drop from its predecessors. Even today, there are only a few full-frame SLRs from Canon and Nikon (and soon, rumour has it, Sony), ranging from $2500 to $8000.

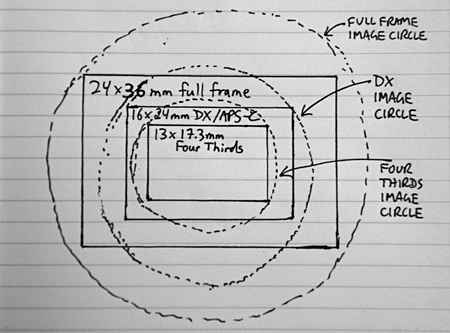

Most people who buy cameras are never going to spend that kind of money, so the solution was to make the sensors smaller (and thus cheaper to manufacture). Most digital SLRs have sensors with dimensions called "APS-C" or "DX" size, which is roughly 16 x 24 mm. Cameras using the Four Thirds system developed by Olympus and Panasonic have even smaller sensors, 13 x 17.3 mm. Most digital point-and-shoot cameras use smaller sensors still.

What does that mean for lenses? Two different things:

- Lens makers can manufacture lenses that project a smaller image circle for those smaller sensors, or

- Existing full-frame lens designs can work with smaller sensors, but those sensors only capture the middle portion of the image circle.

What's nice is:

- Someone like me, who already had a couple of lenses for his Nikon film camera, can buy a Nikon digital SLR (a D50, in my case) and mount those lenses right on it. They work great, even though the camera has a DX-sized sensor in it. The full-frame lenses project an image circle that's too big, but that's okay: the sensor just picks up the middle of that circle, and ignores the edges. Same for anyone with recent film lenses from Canon, Pentax, or other makers.

- Nikon, Canon, Pentax, Olympus, Sigma, Tamron, and other lens manufacturers can make lenses optimized for the DX-sized or Four Thirds sensors—lenses that project a smaller image circle. For a given focal length, those lenses can be smaller, lighter, and less expensive because they don't need as much precision-ground glass to project that smaller circle.

- It's also possible to make reasonably priced zoom and super-wide-angle lenses in focal-length ranges that would be extremely expensive for full-frame cameras. Again that's because of the smaller image circle they project. I have a lens for my D50's DX sensor that is an 18-135 mm zoom, and it cost a few hundred bucks. A lens like that for a full-frame camera would be huge and cost thousands, if it could be made at all.

- For point-and-shoot digicams with even smaller sensors, the lenses can be really tiny and inexpensive, because their image circles are even smaller in diameter. So you can get super-thin and small cameras to fit in your pocket and still take decent photos—much smaller and thinner than any 35 mm pocket cameras ever were.

There are problems too. Smaller sensors tend to create more image noise, especially as manufacturers pack more and more megapixels into them. Bigger sensors, while expensive, can not only handle more pixels cleanly, but can also be designed to work better in lower light. Yet even aside from those issues, different sensor sizes make things messy.

What does "35 mm equivalent" mean?

It turns out that the focal length for a "normal" lens (neither wide-angle nor telephoto), where the objects in the photograph appear in proper proportion as we see with our eyes, isn't universal. It depends on the size of the sensor or film frame. And, as luck would have it, a normal focal length is about the diagonal width of a film frame.

So for a frame of 135 film, or a full-frame sensor, a normal lens would have a focal length of 43.3 mm. (Most often, lens makers create 50 mm lenses instead, probably for technical reasons I don't understand, but that's close enough.) However, for a DX-sized sensor, a normal lens would instead be 28.4 mm. For a Four Thirds sensor, you're looking at 21.6 mm, almost exactly half the focal length of a normal lens for a full-frame SLR.

Point-and-shoot digicams with smaller sensors use even shorter focal lengths for a normal view. And for all those smaller sensors, wide-angle and telephoto mean different things too—my wife's Canon A540 has a 5.8-23.2 mm zoom lens, for instance. The whole range would be super-wide on a full-frame camera, but for a sensor only about 10 mm across, that lens covers medium-wide to medium-telephoto.

Point-and-shoot digicams with smaller sensors use even shorter focal lengths for a normal view. And for all those smaller sensors, wide-angle and telephoto mean different things too—my wife's Canon A540 has a 5.8-23.2 mm zoom lens, for instance. The whole range would be super-wide on a full-frame camera, but for a sensor only about 10 mm across, that lens covers medium-wide to medium-telephoto.

(Incidentally, it works the other direction as well. Medium-format cameras like Hasselblads use a much larger film frame or digital sensor, so a normal lens has a focal length of 80 mm or even 120 mm.)

All this makes shopping for a digital camera complicated. 50 mm is a normal lens on a full-frame SLR, but normal is 33 mm on a DX sensor, 25 mm on Four Thirds, and perhaps 8 mm on a point-and-shoot.

For point-and-shoot cameras it's actually worse than that. With different-sized tiny sensors, even different models from the same manufacturer might have different focal lengths for the same fields of view, and most camera buyers aren't in the mood for making frame-ratio calculations in the store.

So most smaller cameras list their lens zoom ranges as 35 mm equivalents. On my wife's Canon A540, for instance, the only place you'll see that 5.8-23.2 mm specification is on the lens itself. Marketing materials describe the lens as a "35-140 mm equivalent" in 35 mm-film full-frame focal lengths.

What does "crop factor" mean?

There's another way to look at that same relationship between full-frame and smaller sensors. Look again at the image circles for the various different sizes of sensors, and compare that to the field-of-view diagram I showed for wide angle, normal, and telephoto lenses:

Left, sensor size image circles. Right, focal length fields of view.

Notice that, since the smaller sensors cut off the outer portion of the image circle, they essentially crop the picture to the centre portion only. And cropping narrows the angle of view of a picture, similar to using a lens with a longer focal length. But cropping does it at the focal plane at back of the camera instead of at the front of the lens. (You can even crop the image later, in a program like Photoshop, effectively turning a normal-lens picture into a telephoto shot—but at the cost of a fuzzier picture, because you delete pixels too.)

Since both a smaller sensor (cropping the image) and a longer focal length (closer perspective) narrow the angle of view of a scene, you can treat them as the same thing. A full-frame sensor (measuring 43.3 mm corner to corner) is about 1.5 times further across than a DX-sized sensor (measuring 28.4 mm corner to corner). That means the angle of view for a lens of any particular focal length is 1.5 times wider on a full-frame sensor than a DX sensor.

Remember that a 200 mm telephoto lens provides an angle of view 12° across on a full-frame sensor. But a DX sensor crops that down, dividing it by 1.5, so the angle of view is only 8°. That's the same angle of view as a 300 mm lens would have on a full frame, so you can say that the DX sensor makes a 200 mm lens behave like a 300 mm lens. Any lens used with a DX sensor will behave like a lens with 1.5 times the focal length. (Or, more accurately, the way a lens 1.5 times longer would behave on a full-frame sensor.)

That 1.5-times multiplier is called the crop factor or focal length multiplier of a sensor, which expresses two things:

- The diagonal width of a full-frame sensor compared to the cropped sensor.

- How much longer a lens would have to be to project the same angle of view onto a full-frame sensor.

Neatly, those are the same number, because the ratios are the same. Both of them are like zooming in 1.5 times on a full-frame image, so you can only see the middle part.

The Four Thirds sensor is even smaller, about 21.6 mm across. Since that's about half the diagonal width of a full frame, lenses connected to a Four Thirds camera have a crop factor of 2.0, so a 200 mm lens behaves like a 400 mm lens. And a 25 mm lens behaves like a 50 mm lens.

Once you get to point-and-shoot digicams, the crop factors get silly. My wife's Canon has a crop factor of about 6.0, for instance (which is how a 5.8-23.2 mm lens becomes "35-140 mm equivalent"). So the math is the same. Which numbers you see depends on marketing considerations:

- Because point-and-shoot cameras come with a single zoom lens, and because their crop factors are pretty extreme, they're usually advertised in full-frame equivalent terms ("35-140 mm equivalent"). That makes it simple to compare cameras.

- Since digital SLRs have interchangeable lenses, they're usually advertised using the crop factor ("1.6 focal length multiplier") instead—you might be putting all sorts of lenses on them, and it's less confusing if those lenses advertise their actual focal lengths. That makes it simple to compare lenses.

Interestingly, if camera manufacturers used the same terms in describing sensor sizes as they do with resolution (megapixels), they'd have to say that a DX sensor is only 43% the resolution of a full-frame sensor, and a Four Thirds sensor is only 25%! That's another reason why crop factor is the term they prefer.

Tradeoffs

The math makes it seem like you can just shrink your sensor and get more telephoto power for free. That's not quite true:

- Smaller sensors are noisier, as I've already mentioned.

- It's harder to get lots of pixels on them without microscopic electrical interference degrading the image, so it's also harder to make small sensors perform well in low light.

- There are changes in the depth of field: for a given field of view and lens aperture, smaller sensors put more of the image in focus. That's fine if you want deep focus, but if you prefer those nice out-of-focus backgrounds I described in my aperture and f-stops article, it will be harder to accomplish with a smaller sensor.

There are also problems at the wide-angle end. I have a 24 mm lens that gives a very wide field of view on my film camera, but on my DX-format digital SLR (1.5 crop factor), it acts like a 36 mm lens, which isn't all that wide at all. For a similar view, I would need a 16 mm lens, or maybe 18 mm if I don't mind a little closer view.

Building a lens that wide which works on both DX and full-frame sensors is difficult and costly—Nikon and Canon make them, but they cost at least $1500. Now, you can get 16 mm or 18 mm lenses (or zooms that go that wide) for digital SLRs, for much less money. But they are "digital only"—being built smaller and less expensively, they project a smaller image circle, which means that if I put my 18-135 mm DX zoom lens on my old Nikon F4 film camera, there's a big black vignette circle around the image when I look through the viewfinder and take photos:

So a serious wide-angle lens for a DX camera could be pretty much useless on a full-frame camera, unless you spend a lot of money. And the problem only gets worse with smaller sensors like Four Thirds.

It's all relative to full-frame

The full-frame 35 mm film size, which camera and lens designers have been working with for a century or so (it became an accepted standard for movies in 1909), remains an excellent compromise between image quality and portability. Some people still prefer medium-format cameras, and will pay tens of thousands of dollars for a digital Hasselblad, and thousands more for lenses, all of which are beastly to lug around. Most of us are content with smaller-sensor SLRs and point-and-shoot pocket cams.

But most professionals and many enthusiastic amateurs are returning to that full-frame sensor size, and in the past few years cameras with sensors that size have become at least somewhat affordable (if you consider $2500 cheap). That will likely continue, and full-frame cameras will get less expensive.

So in a few years, we could be back to the same old 35 mm standard popularized by Leica more than 80 years ago. Even if not, it looks like we'll be speaking in terms relative to that old 135 full frame for a long time to come.

Read more

Some useful resources:

- Wikipedia: The Science of Photography

- Wikipedia: 135 film

- Wikipedia: Crop factor

- Ken Rockwell: Crop Factor

- DSLR Magnification

- Crop Factor Explained

- The Field of View Thing

« Previous: apertures and f-stops

Next: shutters, flashes, and sync speed »

Labels: barcamp, cameraworks, geekery, photography

Comments:

This is a great series. This is the first article I read in it and I found it really interesting. You've done a great job of making it so simple that I am left wondering if I really knew that all along or if my brain is just trying to convince me that it did. Even if I did know parts of it at a theoretical level, I definitely can explain it better now. In any case, this particular article kind of helped inspire me to start my own blog, about something I know a little bit about... high school robotics competitions. I've set up camp at https://botshop.wordpress.com for now, but will probably move it over to our team's website https://www.trobotics.ca this winter.

In any case, thanks for the inspiration that comes from your writing.