Hit me

Permalinks to this entry: individual page or in monthly context. For more material from my journal, visit my home page or the archive.

UPDATE: Three days after I wrote this post, Bill Carson, the guitarist for whom Leo Fender most directly designed the Stratocaster guitar, died. There's a good biography of Carson on the Fender site. (Fender himself died in 1991.)

UPDATE: Three days after I wrote this post, Bill Carson, the guitarist for whom Leo Fender most directly designed the Stratocaster guitar, died. There's a good biography of Carson on the Fender site. (Fender himself died in 1991.)

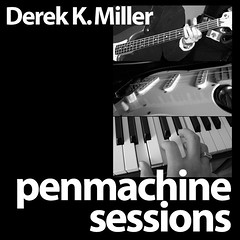

In the 12 years since I quit being a musician full time, and 25 years since I stopped taking guitar lessons, music has become more important in my life, not less. More people hear my tunes through the Internet than ever did when my band traveled from bar to bar on B.C.'s winding highways. My daughters both study piano now, an instrument I knew nothing about before they began. (My oldest, who turns nine in two days, managed an astonishing 84%—First Class Honours—on her Grade 1 Royal Conservatory exam in January.)

We have iPods throughout the house, and iTunes libraries well into the tens of gigabytes. I even co-host a podcast about making and recording music. My home office is stuffed to the brim with cheap but well used drums, keyboards, PA gear, microphones, effects, cables, and of course, guitars.

There's a certain fetishism among guitar players—they are, like many musicians, extremely particular about their instruments, right down to the very slightest curve of the fretboard and the type of lacquer used to finish the body wood. Recently, there has even been a trend for manufacturers to create slavish (and very expensive) clones of famous instruments, right down to measuring and duplicating the scrapes, nicks, wear, oil stains, and cigarette burns of the originals.

I find that weird, but I do understand how a particular instrument can speak to, or through, its player. I'm a pretty mediocre guitarist, but nevertheless, there are five guitars in this house: the classical guitar I learned on when I was 10; an old, cheap Squier Stratocaster I bought and souped up a bit in 1990; a Godin LG electric I found a couple of summers ago; my daughter's half-scale Chinese-made Northland steel string acoustic; and a heavily modified Yamaha Pacifica I picked up in Seattle last year.

Despite all those choices, I consistently find myself gravitating to the Strat. I like the feel of the neck of the Pacifica better, the Godin is better built, and the acoustic guitars of course have their place, but in the end I get the most diverse, satisfying tones from my scraped-up Squier with its low-end pickups and laminated, slightly too-heavy body.

My latest podsafe instrumental MP3, "Fakeout," is a perfect example. I wanted a chiming, chunky, articulate, and focused sound from the guitar, and I knew from the outset that the Stratocaster would give it to me. I was quite right—it's probably the best guitar tone I've ever recorded, even better than what I imagined before I started.

There's a reason that Leo Fender's Stratocaster design, refined in a couple of years of work in the mid-1950s, remains almost entirely unchanged more than 60 years later. There have been innumerable attempts, from the Fender company and all others, to do better, but the retro-futuristic shape of the body and neck, the headstock, the controls, the bridge, the angled cable jack, and the three hum-susceptible single-coil pickups were the same in 1954 as they were in 1990, and as they are in 2007.

Why? Because the Strat works, for country pickers, metalheads, blues benders, avant-garde experimentalists, bar-band truck stompers, pop studio sidemen, polka rhythm players, psychedelic dropouts, reggae chanksters, world music fusionsts, jazzbos, neoclassical prog-rockers, drum-n-bass DJs in need of some six-string attack, and students just starting out. No other guitar—no other single instrument design, except perhaps the human voice—has been the right sound in so many diverse circumstances.

Music is a great mystery. Why do we humans enjoy it? How and why can we distinguish such remarkable subtleties in sound and timing? Why do I, for instance, prefer the sound of a set of overdriven EL84 vacuum tubes in a guitar amplifier to that of a pair of 6L6 tubes, when neither was designed to be overdriven in the first place?

There's pleasure in not knowing.