The detonator

Permalinks to this entry: individual page or in monthly context. For more material from my journal, visit my home page or the archive.

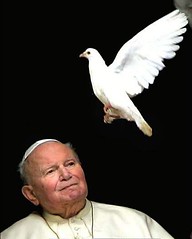

As someone who is neither a Catholic nor religious, the death of Pope John Paul II is much less personal for me than for the 1.2 billion adherents of his church around the world. Yet he is the only pope I remember clearly: the headlines from the brief reign of his predecessor John Paul I in 1978, when I was nine years old, are vague, and Paul VI is a historical shadow to me.

As someone who is neither a Catholic nor religious, the death of Pope John Paul II is much less personal for me than for the 1.2 billion adherents of his church around the world. Yet he is the only pope I remember clearly: the headlines from the brief reign of his predecessor John Paul I in 1978, when I was nine years old, are vague, and Paul VI is a historical shadow to me.

As John Paul II always reminded the world, despite humanity's great achievements in technology and knowledge in the past 100 years, the 20th century was one of great wickedness. His role was to fight that wickedness, in all the forms he and his church perceived it.

Even for those who disagreed with or actively opposed him, or those from radically different intellectual and spiritual traditions, the Pope was a man of unusual principle. Unlike so many politicians and others who bend concepts such as "sanctity of life" to fit their current priorities, John Paul was (as far as I know) consistent in his philosophy, following it through even when it was unpopular, or personally dangerous for him.

In many ways he was very conservative, slowing some of the changes begun by the Second Vatican Council and remaining firmly traditional in his views of sexuality, secular law, and women. He was, to put it plainly, an old man who opposed birth control. But he was also a radically new kind of pope: a world traveler on an unprecedented scale, a man in some ways more concerned with the poor and oppressed of the earth (regardless of their religion—but also limited by his beliefs in what he thought was best for them) than with the European heart of his church—and a celebrity superstar, one of the most famous and widely recognizable people in history. (Whose face is better known? Einstein's? Hitler's? Those are painful ironies.)

He forced everyone who heard him to think about the big questions: What is life? What is peace? What is love? What is good? What is right? (His answers sometimes differed from mine, but he made me ask.) In his many appearances around the globe, he probably addressed a larger proportion of the human population in person than anyone ever has. No matter how you feel about his message—or really, his many messages—no one can deny that he was a profoundly important man. One who presided over the key mysteries, myths, ideals, and beliefs of a vast number of people, and one who pushed them to real ends.

Pointedly, maybe Eastern European Communism would have collapsed without John Paul II, but would it have happened as soon as it did, and without much more dreadful bloodshed? Probably not. Former Polish Communist leader General Jaruzelski agrees with historians and analysts worldwide that the Pope's return to his home country in 1979 was the beginning of the end for the Iron Curtain. It may have taken another decade to take effect, but the general said, "that was the detonator."