Penmachine

25 January 2010

Ping-pong to the stars!

More than 30 years ago, I was a Star Wars–obsessed kid, like most of the pre-teen population at the time. I had a ton of action figures, as well as a large Millennium Falcon playset for them (which I'm pretty sure is in our attic somewhere).

My parents indulged my obsession in a pretty cool way. In our basement we had a ping-pong table we didn't use much. Because my dad's job involved installing and repairing vending machines and video game consoles of various sorts, he also had access to extremely large and sturdy cardboard boxes. We took a number of those boxes and connected them with duct tape to form a series of tunnels around the table—for me and my friends, they made corridors like the ones in the Falcon, though we had to crawl through them rather than walk.

The central area under the table was like the lounge where Chewbacca and the droids play 3D chess and Luke learns to use his lightsaber. To top it off, my dad installed a modified old broken video game console at one end of the table. It included an aircraft-style steering console and a radar screen with lights behind it, as well as buttons to generate laser-like noises.

As you can imagine, this was pretty much the Coolest Thing Ever when I was nine or ten years old. My friends and I played in that spaceship so much that we had to replace the boxes periodically, because they tended to get destroyed as we thrashed our way around the cardboard hallways, perpetually escaping asteroid fields and attacking Imperial forces.

I can't remember playing ping-pong even once on that table.

Labels: family, home, memories, space, starwars

17 January 2010

Considering "Avatar"

I'm still not sure quite what I think—on balance—about Avatar, which my wife and I saw last week. In one respect, it's one of very few movies (pretty much all of them fantasy or science fiction) that show you things you've never seen before, and which will inevitably change what other movies look like. It's in the company of The Wizard of Oz, Forbidden Planet, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Star Wars, Blade Runner, Tron, Zelig, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Jurassic Park, Babe, Toy Story, The Matrix, and the Lord of the Rings films. It's tremendously entertaining. Anyone who likes seeing movies on a big screen should watch it.

I also don't know if anyone is better at choreographing massive action sequences than Avatar's director, James Cameron—nor of making a three-hour film seem not nearly that long. Maybe, with its massive success, we'll finally see fewer movies with the distinctive cold blue tint and leathery CGI monsters stolen from the Lord of the Rings trilogy. (Maybe in a few years we'll all be tired of lush, phosphorescent Pandora-style forests instead.) Avatar is also the first truly effective use of 3D I've seen in a film: it's not a distraction, not a gimmick, and not overemphasized. It's just part of how the movie was made, and you don't have to think about it, for once.

But a couple of skits on last night's Saturday Night Live, including "James Cameron's Laser Cats 5," in which both James Cameron and Sigourney Weaver appeared, reminded me of some of Avatar's problems:

- Cameron has been thinking about this project since the beginning of his career over three decades ago, and it shows. Or rather, it shows in every other movie he's made. That's because Avatar includes a grab-bag of common Cameron concepts: humanoids that aren't quite what they seem (The Terminator and Terminator 2); kick-ass interstellar marines—including a butch-but-sensitive Latino woman—piloting big walking and flying machines (Aliens); state-of-the-art CGI effects pushed to their limits (The Abyss, Terminator 2, and Titanic); money-grubbing corporate/elite bad guys (Aliens, Titanic), hovering, angular, futuristic transport vehicles (True Lies, The Terminator, The Abyss, Aliens); a love story that turns one of its participants away from societal conventions (Titanic); people traveling to distant planets in suspended animation (Aliens), and of course a lot of stuff that Blows Up Real Good.

- The storyline, despite its excellent execution, is remarkably simplistic, and could easily have been adapted from a mid-tier Disney animation like The Aristocats or Mulan, or (most pointedly) Pocahontas. It's the Noble Savage rendered in blue alien flesh. No doubt much of that is intentional, since some of our most powerful and lasting stories are simple. But I think all the talent and technology behind this movie could have served something more sophisticated, or at least more morally nuanced.

- With all the spectacle of Pandora—the glowing forest plants, the bizarre pulsing and spinning animal life, the floating mountains, the lethal multi-limbed predators—somehow it didn't feel alien enough to me. The most jarring foreign feeling came in the views of Pandora's sky, reminding us that it is not a planet but one of many moons of a looming, ominous gas giant like Jupiter. The humanoid Na'vi, despite all the motion capture that went into translating human actors' performances into new bodies, still seem, in a way, like very, very well-executed rubber suits. The pre-CGI aliens of Aliens (especially the alien queen) were, to me, more convincing despite often actually being people in suits.

- Overall, Avatar isn't James Cameron's best film. I'd choose either Aliens or Terminator 2: Judgment Day as superior. I remember each one leaving me almost speechless. That's because they were exhilarating and—more important—profoundly satisfying, both emotionally and intellectually. Avatar, despite its many riches, didn't satisfy me the same way.

Now, if you're among the 3% of people who haven't seen Avatar yet, I still recommend you do, in a big-screen theatre, in 3D if you can. Like several of the other technically and visually revolutionary movies I listed in my first paragraph (Star Wars and Tron come to mind), its flaws wash away as you watch, consumed and overwhelmed by its imaginary world.

James Cameron apparently plans to make two Avatar sequels. Normally that might dismay me, but his track record of improving upon the original films in a series, whether someone else's or his own (see my last bullet point above), tells me he might be able to pull off something amazing there. Now that he has established Pandora as a place, and had time to develop his new filmmaking techniques, it could be very interesting to see what he does with them next.

Labels: film, movie, review, sciencefiction, space

20 November 2009

See the world

Since 1972, the Landsat satellites have been photographing the surface of the Earth from space. However, the amount of data involved meant that only recently could researchers start assembling the millions of images into an actual map, where they could all be viewed as a mosaic.

Since 1972, the Landsat satellites have been photographing the surface of the Earth from space. However, the amount of data involved meant that only recently could researchers start assembling the millions of images into an actual map, where they could all be viewed as a mosaic.

NASA has posted an article explaining the process. The map covers only land areas (including islands), but it is not static—it includes data from different years so you can see changes in land use and climate.

Here's the neat thing. Back in the 1980s, while the information was there, putting even a single year's images into a map would have cost you at least $36 million (USD). Now you can get the whole thing online for free. Take a look. If you poke around, there's a lot more info than in Google Earth.

Labels: astronomy, geekery, photography, science, space

24 July 2009

Splashdown

Today we mark 40 years since the Apollo 11 Command Module Columbia splashed down in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, a few hundred kilometres from the now-closed Johnston Island naval base:

Our first (and sixth last!) trip to the surface of the Moon was over. The seared, beaten Columbia (weighing less than 6,000 kg, and which had remained shiny and pristine until its re-entry into the Earth's atmosphere), with its passengers, was the only part of the titanic Saturn V rocket (3 million kg) to return home after a little over one week away. Every other component had been designed to burn up during launch or return, to stay on the Moon's surface (where those parts remain), to smash into the Moon, or to drift in its own orbit around the Sun.

All three astronauts returned safely, and suffered no ill effects, despite being quarantined for two and a half weeks, until August 10, 1969, when I was six weeks old.

Labels: anniversary, astronomy, holiday, moon, oceans, science, space

21 July 2009

Going home

Just before noon today, Pacific Time, marks exactly 40 years since Neil armstrong and Buzz Aldrin launched their Lunar Module Eagle and left the surface of the Moon, to rendezvous with their colleague Michael Collins in lunar orbit:

They were on their way home to Earth, though it would take a few days to get back here.

Labels: anniversary, astronomy, holiday, moon, science, space

20 July 2009

Today was the day

The beginnings of human calendars are arbitrary. We're using a Christian one right now, though the start date is probably wrong, and the monks who created it didn't assign a Year Zero. Chinese, Mayan, Hindu, Jewish, Muslim, and other calendars begin on different dates.

If we were to decide to start over with a new Year Zero, I think the choice would be easy. The dividing line would be 40 years ago today, what we call July 16, 1969. That's when the first humans—the first creatures from Earth of any kind, since life began here a few billion years ago—walked on another world, our own Moon:

They landed their vehicle, the ungainly Eagle, at 1:17 p.m. Pacific Daylight Time (the time of my post here). Just before 8 PDT, Neil Armstrong put his boot on the soil. That was the moment. All three of the men who went there, Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins, are almost 80 now, but they are still alive, like the rest of the relatively small slice of humanity that was here when it happened (I was three weeks old).

If the sky is clear tonight, look up carefully for the Moon: it's just a sliver right now. Although it's our closest neighbour in space, you can cover it up with your thumb. People have been there, and when the Apollo astronauts walked on its dust, they could look up and cover the Earth with a gesture too—the place where everyone except themselves had ever lived and died. Every other achievement, every great undertaking, every pointless war—all fought over something that could be blotted out with a thumb.

Even if it doesn't start a new calendar (not yet), today should at least be a holiday, to commemorate the event, the most amazing and important thing we've ever done. Make it one yourself, and remember. Today was the day.

Labels: anniversary, astronomy, holiday, moon, science, space

16 July 2009

Launch day

Forty years ago today. July 16, 1969, 9:32 a.m. EDT, Launch Complex 39A, Cape Canaveral, Florida. Three nearly hairless apes—human beings in pressure suits—left for the Moon:

They were aboard the world's greatest machine, which put out about 175 million horsepower during launch. Less than three hours later, they exited Earth orbit and were on their way.

Labels: anniversary, astronomy, moon, science, space

05 July 2009

Links of interest 2006-06-28 to 2006-07-04

Once again, while I'm on my blog break, my edited Twitter posts from the past week, newest first:

- Photo of Obama picking up his infamous housefly victim.

- Guess that U2 iPod is never coming back.

- And now: "Ant and Buttercup," my debut HD macro closeup movie from our summer garden:

- My first experiments with off-camera flash during close-up photography:

- If I'm passed at high speed by someone with a Washington plate BOKEH, I now know who it is. He says he'll wave.

- Mammals will play, even between species, even when you'd never expect it—wild polar bear and huskies (slide show via Dave Winer).

- A couple of crows are nesting nearby; they keep landing in our birdbath and on the house and lamp stands, looking ominous. Too smart, crows.

- Sitting in a B.C. garden

No waiting for the sun - CompuServe finally shuts down.

- Just in case you're looking for a $2.1 million convertible.

- Congratulations to Buzz Bishop, Jen, and Zacharie.

- I presume this tiny USB-driven monitor screen is Windows-only, because of drivers? Looks pretty swell. (Via Neal Campbell.)

- Definitive proof I'm not afraid of heights: I love this idea.

- Via John Biehler, I found that as well as MythBuster Adam Savage, his co-workers Grant Imahara and narrator Robert Lee are also on Twitter.

- When I had my first Nikon 25 years ago, I wouldn't have believed I'd ever own one (a D90) with 66 pages of the manual (out of a couple hundred total, in a 16 MB PDF file) just for menu options. Then again, 25 years ago, a friend showed me a shoulder-mounted Betamax camera from Hong Kong, and it was the latest in high tech video too.

- That's the funkiest beat I've ever heard a marching band play (via Jared Spool). Maybe some James Brown next?

- Has anyone pinpointed the exact day that Victoria Beckham stopped being able to smile? Angus Wilson speculates, "whatever day she began to look less like a hot English babe and more like a velociraptor."

- Meg Fowler: "Sarah Palin's quitting politics like Ann Coulter's quitting evil."

- As the 40th anniversary of the first moon landing approaches, some fabulous photos from the missions, via Bad Astronomy.

- From Ben Englert: "Thank you, gdgt, for institutionalizing the arduous task of dick-measuring by figuring out who has more toys."

- Ten best uses of classical music in classic cartoons.

- Our fridge magnet: "I love not camping."

- How did I manage to bite the inside of my upper lip while eating a peach? If this were high school, the guys would say, "Each much?"

- Back to short hair for summer. And now I realize that it's Colbert hair.

- I think my guts have calmed down now. Time for bed. In the meantime, enjoy a naked Air New Zealand flight crew.

- In case you'd like to watch Jeff Goldblum reporting on his own "death," on Colbert Monday: links for Canada and the U.S.A. (sorry if you're elsewhere!).

- Didn't attend various Canada Day parties because of tired family and my usual intestinal side effects. Hope you had fun in my stead. Managed to avoid intestinal chemo side effects for a few days, but they're back with a vengeance. Could be a looooong night. (And it was. At 2 a.m., my chemo side effects were "over" and I went to bed. Bzzt! Wrong! Finally got to sleep at 9 a.m., woke up at 1 the next afternoon. As Alfred E. Neuman says, Yecch.)

- Whatever you think of the 2010 Olympics here in Vancouver, VANOC is doing a good job with graphic design.

- I, too, welcome our new ant overlords.

- I had no alcohol on my birthday yesterday, but still had a Canada Day headache on July 1. Here's my new free instrumental.

- Inside Home Recording #72 is out: Winners, Studio Move, Synth 101, Suckage! AAC enhanced and MP3 audio-only versions.

- Normally I really like our car dealer's service dept, but today the steering wheel came back oh-so-slightly to the left. They had to re-fix it.

- World's geekiest pillows (via Chris Pirillo). My guess: they didn't license the Apple icons. Get the pillows while you can.

- Officially made it to 40. Thanks everybody for the birthday wishes. Most people are bit melancholy to reach 40, but I am extremely glad to have made it.

- Just returned from a Deluxe Chuck Wagon burger (with cheese) at the resurrected Wally's Burgers in Cates Park, North Vancouver:

- From Rob Cottingham: "The hell with putting a ring on it. If you liked it, you shoulda made a secure offsite backup."

- Info about recording old vinyl records into a computer: You need a proper grounded phono preamp, with good hot signals into an audio interface or other analog-to-digital converter. A new needle might be wise if yours is old, but the real phono preamp (w/RIAA curve) is the most necessary bit after that. Route it thru an old stereo tuner if needed! See my old post from 2006 at Inside Home Recording.

- Myth confirmed: Baby girl evidence (named Stella) shows MythBusters' Kari Byron actually was pregnant.

- My new Twitter background image is the view we saw at sunset during my birthday party on Saturday. (I've since replaced it again.)

- Back from another fun sunny summer BBQ at Paul Garay's new house—it's been a burgers-n-beer weekend.

- Photos from my 40th birthday party now posted (please use tag "penmachinebirthday" if you post some).

Labels: animals, band, birthday, cartoon, family, food, geekery, insidehomerecording, linksofinterest, moon, movie, music, mythbusters, news, paulgaray, photography, politics, space, transportation, usb

28 June 2009

Links of interest 2006-06-21 to 2006-06-27

While I'm on my blog break, more edited versions of my Twitter posts from the past week, newest first:

- My wonderful wife got me a Nikon D90 camera for my 40th birthday this week. I'm thinking of selling my old Nikon D50, still a great camera. Anyone interested? I was thinking around $325. I also have a brand new 18–55 mm lens for sale with it, $150 by itself or $425 together. I have all original boxes, accessories, manuals, software, etc., and I'll throw in a memory card, plus a UV filter for the lens.

- Roger Hawkins's drum track for "When a Man Loves a Woman" (Percy Sledge 1966): tastiest ever? Hardly a fill, no toms, absolutely delicious.

- Thank you thank you thank you to everyone who came to my 40th birthday party—both for your presence and for the presents. Photos from the event, held June 27, three days early for my actual birthday on Tuesday, are now posted (please use tag "penmachinebirthday" if you post some yourself).

- I think Twitter just jumped the shark. In trending topics, Michael Jackson passed Iran, OK, but both passed by Princess Protection Program (new Disney Channel movie)?

- AT&T (and Rogers, presumably) is trying to charge MythBusters' Adam Savage $11,000 USD for some wireless web surfing here in Canada.

- After more than 12 years buying stuf on eBay, here's our first ever item for sale there. Nothing too exciting, but there you go.

- Michael Jackson's death this week made me think of comparisons with Elvis, John Lennon, and Kurt Cobain. Lennon and Cobain still seemed to have some artistic vitality ahead of them. Feel a need for Michael Jackson coverage? Jian Ghomeshi (MP3 file) on CBC in Canada is the only commentator who isn't blathering mindlessly. But as a cancer patient myself, having Farrah Fawcett and Dr. Jerri Nielsen (of South Pole fame) die of it the same day is a bit hard to take.

- Seattle's KCTS 9 (PBS affiliate) showed "The Music Instinct" with Daniel Levitin and Bobby McFerrin. If you like music or are a musician, it's worth watching, even if it's a bit scattershot, packing too much into two hours.

- New rule: when a Republican attacks gay marriage, lets assume he's cheating on his wife (via Jak King).

- The blogs and podcasts I'm affiliated with are now sold on Amazon for its Kindle e-reader device, for $2 USD a month. I know, that's weird, because they're normally free, and are even accessible for free using the Kindle's built-in web browser, so I don't know why people would pay for them—but if you want to, here you go: Penmachine, Inside Home Recording, and Lip Gloss and Laptops. Okay, we're waiting for the money to roll in...

- Great speech by David Schlesinger from Reuters to the International Olympic Committee on not restricting new media at the Olympics (via Jeff Jarvis).

- TV ad: "Restaurant-inspired meals for cats." Um, have they seen what cats bring in from the outdoors?

- I planned to record my last segment for Inside Home Recording #72, but neighbour was power washing right outside the window (in the rain!). Argh.

- You can't trust your eyes: the blue and green are actually the SAME COLOUR.

- Can you use the new SD card slot in current MacBook laptops for Time Machine backups? (You can definitely use it to boot the computer.) Maybe, but not really. SDHC cards max out at 32GB (around $100 USD); the upcoming SDXC will handle more, but none exist in Macs or in the real world yet. Unless you put very little on the MacBook's internal drive, or use System Preferences to exclude all but the most essential stuff from backups, then no, SD cards are not viable for Time Machine.

- Some stats from Sebastian Albrecht's insane thirteen-times-up-the-Grouse Grind climb in one day this week. He burned 14,000+ calories.

- Even though I use RSS extensively, I find myself manually visiting the same 5 blogs (Daring Fireball, Kottke, Darren Barefoot, PZ Myers, and J-Walk) every morning, with most interesting news covered.

- I never get tired of NASA's rocket-cam launch videos.

- Pat Buchanan hosts conference advocating English-only initiatives in the USA. But the sign over the stage is misspelled.

- Who knew the Rolling Stones made an (awesome) jingle for Rice Krispies in the mid-1960s?

- Always scary stuff behind a sentence like, "'He is an expert in every field,' said a church spokeswoman."

- Kodachrome slide film is dead, but Fujichrome Velvia killed it a long time ago. This is just the official last rites.

- My friends Dave K. and Dr. Debbie B. did the Vancouver-to-Seattle bicycle Ride to Conquer Cancer (more than 270 km in two days) last weekend. Congrats and good job!

- My daughter (11) asks on her blog: "if Dad is so internet famous, I mean, Penmachine is popular, then, maybe I am too..."

- Evolution of a photographer (via Scott Bourne).

Labels: amazon, apple, backup, birthday, cancer, film, geekery, linksofinterest, music, news, olympics, photography, politics, religion, science, space, television, twitter

06 June 2009

Han Solo, P.I.

I would have loved this show about 30 years ago:

Via All Things D.

Labels: humour, memories, movie, space, starwars, television

21 December 2008

Science is amazing

Okay, so here's a movie (via Bad Astronomer) of Jupiter's moon Ganymede passing behind the giant planet. Pretty darn amazing and cool:

Now here's the really amazing part. The movie was assembled from a series of images taken not from a probe sent to Jupiter from Earth. Nope, they were taken by the Hubble Space Telescope, in low orbit around our own planet. These pictures were taken, over the course of two hours in April 2007, from here, something like 600 million kilometres away from the subjects. The light from Ganymede and Jupiter took almost an hour to reach the Hubble camera.

Talk about your telephoto lens.

Labels: astronomy, movie, photography, science, space, video

14 November 2008

Today, it's Japan, China, and India at the Moon

Remember when the U.S. and Russia were the only countries with space programs and their own rockets? Then came the European Space Agency, mostly launching commercial satellites from French Guyana. Somehow my 1970s kid brain is still stuck in that mindset.

Remember when the U.S. and Russia were the only countries with space programs and their own rockets? Then came the European Space Agency, mostly launching commercial satellites from French Guyana. Somehow my 1970s kid brain is still stuck in that mindset.

But it's wrong, wrong, wrong. Yes, the U.S. still sends plenty of astronauts into orbit, and has wonderful robotic probes venturing throughout the solar system. But how about the Moon? As far as I can tell, the last time America sent anything to the Moon was ten years ago, when the Lunar Prospector orbited, then intentionally crashed into a crater to test for water. Russia hasn't sent anything since the Luna 24 probe in 1976. The ESA was there more recently, with its SMART 1 five years ago.

Who is sending spacecraft to the Moon now? That would be Japan, China, and (most notably today) India, which hit the moon with a flag-painted impact probe sent from its Chandrayaan-1 lunar orbiter mere hours ago.

The U.S. has a lunar orbiter scheduled to launch next year, and both it and Russia have grand plans to send people back, but for now, it is the countries of Asia that are telling us about our nearest neighbour in space. I think that's pretty cool.

Labels: astronomy, geekery, moon, politics, science, space

17 October 2008

Links of interest (2008-10-17):

Sorry, I'm not keeping very good track of my sources for these:

- Eighty-four variations of the iconic Obama "HOPE" poster.

- "...incentive plans based on measuring performance always backfire. Not sometimes. Always."

- "If I have grown more cynical in recent years, it is travel, I think, that has pushed me in this direction. Exploring other parts of the world is beneficial in all the ways it is typically given credit for [...] But traveling can also burn you out, suck away your faith in humanity. You will see, right there in front of you, how the world is falling to pieces."

- A $15 USB controller shaped like the classic Atari 2600 joystick.

- Fabulous video of the recent SpaceX launch—the first successful commercial orbital rocket launch ever. If you're interested, here's a Google Maps satellite photo of the launch facility in the South Pacific, midway between Hawaii and New Guinea.

- Why we can't imagine what it's like to be dead.

- Blues guitar legend Robert Johnson died 70 years ago. Someone might have recently discovered a new photograph of him, one of at most a handful existing.

Labels: death, gadgets, linksofinterest, money, music, photography, politics, space, travel

01 October 2008

I'll be indisposed

I'm having another colonoscopy on Thursday, my first in more than a year and a half. It's in preparation for surgery next week to reconnect my intestines so I can get rid of the bag of poop I've had to keep glued to my belly since the summer of 2007. So I won't be posting here tomorrow, I don't think.

And you know, in the scheme of what I've been through in the past couple of years, a colonoscopy is nothing. If you're over 50 or (like me, it turned out) are otherwise at risk for colorectal cancer, go get one. They give you good drugs, so you won't mind.

In the meantime, check out 50 images in honour of NASA's 50th birthday, via Bill.

Labels: cancer, colostomy, hospital, ileostomy, science, space, surgery

28 September 2008

The world's greatest machines

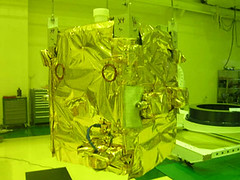

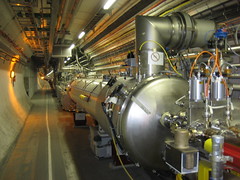

There's been a lot of talk recently about how the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is the largest and most powerful machine ever built. I guess it is that. But there is another machine I still like better: the Apollo Saturn V moon rocket, retired more than 35 years ago. Each one was constructed not for years and years of experiments by thousands of people, as the LHC is, but for a single task lasting a mere week: to get three men to the moon and back.

There's been a lot of talk recently about how the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is the largest and most powerful machine ever built. I guess it is that. But there is another machine I still like better: the Apollo Saturn V moon rocket, retired more than 35 years ago. Each one was constructed not for years and years of experiments by thousands of people, as the LHC is, but for a single task lasting a mere week: to get three men to the moon and back.

The Saturn V was the most powerful machine of its time. I still think it is the most important device we've ever built, and as far as I know it remains the most expensive—in adjusted dollars, the Apollo program cost about $135 billion, many times the price of the LHC.

I've just watched In the Shadow of the Moon again, this time on television. (It was worth seeing in the movie theatre before, for the size of the images.) I was less than three weeks old during the launch and the eventual landing of the Lunar Module. If I'd been an adult, I think I would have burst into tears at both events. I've come pretty close just watching the footage, almost 40 years later.

I've just watched In the Shadow of the Moon again, this time on television. (It was worth seeing in the movie theatre before, for the size of the images.) I was less than three weeks old during the launch and the eventual landing of the Lunar Module. If I'd been an adult, I think I would have burst into tears at both events. I've come pretty close just watching the footage, almost 40 years later.

I'm very happy that people think basic physics important enough to spend billions of dollars constructing the LHC. But, while it is impressive, that device is an experimental apparatus, carefully assembled over many years. Although the Apollo rockets were also a massive endeavour, it happened instead in an astounding rush, a little over eight years from conception to success, less time than it takes for Peter Gabriel to make a new album. It remains the only time we've taken people to another world. That's some really awesome machinery.

Labels: astronomy, moon, movie, science, space

09 March 2008

Links of interest (2008-03-09):

- "You call this traveling? Twenty-one days, 15 countries, 45,000 miles—without setting foot outdoors."

- "The more affluent a country gets, the more things parents come to see as essential for raising children [so] as long as the world keeps creeping out of poverty, families will continue to shrink."

- jamNOW lets you jam online with other musicians, interact with fans, and listen to live streams from nightclubs all over the place. Haven't tried it, so I'm not sure how well it works.

- Looks like the iMac DV in our kitchen is finally officially obsolete. It's slow, but it still works pretty well.

- Are things really this bad for biology teachers in significant portions of the U.S.A.?

- "If all you do is work, your value judgements are unlikely to be sound."

- "I rejoice in this life that I have, and in the grandeur of a world that preceded me, and an earth that will abide without me."

- "Studies have shown that abstinence-only education does virtually nothing to prevent kids from having sex [and that] abstinence-only group[s] used birth control less frequently."

- "When I get a resume, the first thing I do is type the person's name into Google. If nothing comes up, I trash the resume without reading it."

- "I don't want my ISP looking at how I use the Internet to target ads to me, period, any more than I want the phone company listening in on my conversations in order to sell me stuff."

- TripIt looks like one of the best online travel resources out there, though I haven't tried it.

- How to make your website or blog faster.

- The Universe is 13.73 billion years old, give or take only about 120 million years. Now that is a cool finding.

Labels: apple, astronomy, evolution, family, google, linksofinterest, music, school, science, sex, space, travel, web

12 October 2007

Moon men reviewed

My oldest daughter and I saw In the Shadow of the Moon today. She's a nine-year-old Discovery Channel junkie, and so agreed right away when I suggested we go. The screening was sparsely attended because the film has been out for about a month, and it is a documentary, after all.

My oldest daughter and I saw In the Shadow of the Moon today. She's a nine-year-old Discovery Channel junkie, and so agreed right away when I suggested we go. The screening was sparsely attended because the film has been out for about a month, and it is a documentary, after all.

I was three weeks old when Neil Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin landed on the Moon, so obviously I don't remember it. But just as obviously, it's been part of my psyche my whole life, especially because my dad is a keen amateur astronomer, fascinated by the Moon since his childhood. (I even had the privilege of examining some real moon rocks loaned to my grade 8 science lab back in 1982.) I thought I'd seen almost all the lunar footage out there, especially the stuff from Apollo 11.

Wrong. In the Shadow has tons of new stuff, totally aside from the entertaining interviews with the surviving Apollo astronauts (except the notoriously reclusive Neil Armstrong). Slow-motion HD-restored film of snow-like ice shedding from the sides of the Saturn V rocket as it lifts off the pad and slides through clouds of steam rotating across its metal skin. New views of Armstrong descending the ladder of the Lunar Module (LM) for his "one small step." Sound and video of the ground crew wiping their sweaty brows as the LM crew skims their craft over dangerous lunar boulder fields, almost out of landing fuel, trying to find a flat place to set down. Precious, fearsome liquid oxygen—instantly frozen to tiny crystals in space—spewing past the window of the crippled Apollo 13 command module.

Wrong. In the Shadow has tons of new stuff, totally aside from the entertaining interviews with the surviving Apollo astronauts (except the notoriously reclusive Neil Armstrong). Slow-motion HD-restored film of snow-like ice shedding from the sides of the Saturn V rocket as it lifts off the pad and slides through clouds of steam rotating across its metal skin. New views of Armstrong descending the ladder of the Lunar Module (LM) for his "one small step." Sound and video of the ground crew wiping their sweaty brows as the LM crew skims their craft over dangerous lunar boulder fields, almost out of landing fuel, trying to find a flat place to set down. Precious, fearsome liquid oxygen—instantly frozen to tiny crystals in space—spewing past the window of the crippled Apollo 13 command module.

At some moments, I got a bit weepy. We haven't been back to the Moon since I was three, so I don't remember any of the Apollo lunar missions. In the following few years, as I learned about them, I became convinced that moon missions would be common when I grew up. But, as Roger Ebert wrote some years ago, in reviewing Ron Howard's Apollo 13 docudrama:

When I was a kid, they used to predict that by the year 2000, you'd be able to go to the moon. Nobody ever thought to predict that you'd be able to, but nobody would bother.

This film reminded me how amazing it was that we got there at all when we did, at pretty much the first moment it was technically possible. Not safe, not wise, not sensible, just possible. The men in the movie—garrulous and funny Michael Collins, wry Aldrin, grandfatherly Jim Lovell, frail but firm John Young, and stern and trustworthy Gene Cernan among them—are old now, but they were young then (the same age as I am today). They achieved a great thing, maybe the greatest thing anyone has ever done. That's worth remembering.

Labels: astronomy, moon, movie, science, space

04 October 2007

Happy birthday, Sputnik

Back in the late 1970s, a traveling exhibition of Soviet space program artifacts and replicas came to the H.R. MacMillan Planetarium here in Vancouver. My parents had bought a lifetime membership to the Planetarium when it opened in the late '60s, so we went there all the time, and this was a particularly exciting event.

Back in the late 1970s, a traveling exhibition of Soviet space program artifacts and replicas came to the H.R. MacMillan Planetarium here in Vancouver. My parents had bought a lifetime membership to the Planetarium when it opened in the late '60s, so we went there all the time, and this was a particularly exciting event.

The part that made the biggest impression on me was the very loud demonstration scale model of the massive Soyuz rocket that launched (and still launches) Russian space capsules. I remember its distinctly Russian shape, with the flared boosters at the bottom, so different from the straight-arrow American designs such as the Saturn moon rockets.

When I saw the exhibition, Sputnik was not even a quarter century in the past, but to me as a kid it was ancient history. In that time, people had orbited the Earth, gone to the Moon, sent robots throughout the solar system, and were about to launch the first reusable Space Shuttle.

Today is the 50th anniversary of that first-ever Sputnik orbital flight. As far as people going into space, not much genuinely new has happened since I saw those Soviet rockets. We have the space station now (built through cooperation between post-Soviet Russia, NASA, and other space programs around the world), but we're also still flying Soyuz and Shuttle missions, and no one has been back to the Moon since 1972.

Sputnik was the first, and it turns out to have been the model too. Its successors, robotic space probes, have accomplished remarkable things since, from examining the Sun to plunging into the atmosphere of Jupiter, landing on Saturn's moon Titan, and going way beyond. Every day, people across the globe use communications satellites and GPS and satellite views on Google Maps without a second thought. Sputnik, by striking fear of Communist supremacy into our hearts, also energized the Western world's science education programs. Indirectly, I'm probably alive today because of the scientific and medical research prompted by those changes, which improved treatments for both diabetes and cancer.

That tiny beeping metal sphere really did change the world. S dniom razhdjenia, Sputnik.

UPDATE: IEEE Spectrum has a nice feature on the anniversary, including an interview with Arthur C. Clarke in which he points out that "space travel is a technological mutation that should not really have arrived until the 21st century. But thanks to the ambition and genius of [Wernher] von Braun and Sergei Korolev, and their influence upon individuals as disparate as Kennedy and Khrushchev, the Moon—like the South Pole—was reached half a century ahead of time."

Labels: anniversary, astronomy, birthday, science, space