Penmachine

21 April 2010

Back to 1978

A couple of years ago, I bought an old Nikon F4 film camera (introduced in 1988), and I've enjoyed taking pictures with it, especially in black and white. It's a pretty big beast, though, and over time I've been thinking about the first camera I bought for myself in the early '80s, a manual-focus Nikon FG. Then I spotted a surprisingly cheap deal on eBay, and this week it arrived:

It's a Nikon FE, a slightly older (introduced in 1978) and slightly higher-end model than my FG, and it came with a manual-focus 50 mm Nikkor lens. For many years, the electromechanical FE, its companion mechanical FM, and their successors the FE2 and FM2 were often the backup camera bodies of choice for professional photographers—less expensive than the top-of-the-line F2, F3, or F4, but still rugged and simple to use.

Like my F4, this thing feels like a brick, because unlike the digital cameras most people buy today, the FE is almost all metal, including the lens housing. It's also surprisingly small, since it lacks the rubberized covering and big handgrips that digital SLRs like my D90 have. (Since film is out of fashion, the FE also cost me a tiny fraction of the price of the D90.)

Besides my general Gear Acquisition Syndrome and the dirt-cheap price, another reason I bought the FE is that my younger daughter L has been wanting to learn a bit more about photography, and the principles are much easier to demonstrate on an old film camera. With a fixed (non-zoom) lens on it, there are really only three things to adjust: aperture, shutter speed, and focus. DSLRs let you change ISO (sensitivity) and white balance too—among many, many other features—but with the FE those are determined by the film you choose.

I've loaded the FE with some 400-speed black-and-white film, and we'll see how the first photos turn out, and how the photographic experience compares to the F4 and D90. A nice feature of film cameras (despite the inconveniences) is that, whenever you buy new film, you're effectively putting a new sensor inside, so they don't really become obsolete the way digital cameras do.

Labels: cameraworks, family, geekery, nikon, photography

17 March 2010

The Nikon FM3A

Camera nerds have strange obsessions. Among film cameras, the Leica M series of small rangefinder devices is probably top among photo fetishists, who might argue about whether the original 1950s M3 or the current M7 or MP is the optimum design.

Camera nerds have strange obsessions. Among film cameras, the Leica M series of small rangefinder devices is probably top among photo fetishists, who might argue about whether the original 1950s M3 or the current M7 or MP is the optimum design.

But to me, the manual-focus, precision-built electromechanical Nikon FM3A SLR is the real star of these old-school cameras. It was an oddity when Nikon introduced it in 2001—by which time ergonomically-shaped, plastic-bodied autofocus cameras were what almost everyone used, and digital was poised to take over from film almost entirely. (Even the FA of 1983, or the intro-level FG I owned around the same time, had more modern features in many respects.)

But Nikon was intentionally building a modernized retro camera for those fetishists. It offers basic but powerful light-metering, manual focus assistance, fill-flash compatibility, and aperture-priority automation if you want it. But it is also a fully-mechanical machine that will operate perfectly (except for the light meter) without any batteries. All the power to run it can come from energy stored in springs when you ratchet the film advance lever with your thumb, something that's hard to comprehend for anyone who's used to today's battery-sucking digital beasts, or even my 1988 autofocus Nikon F4.

Nikon only made the FM3A for five years, and manufactures nothing at all like it today. (Indeed, almost no one besides Leica makes fully mechanical cameras anymore.) If you can find one, it sells for pretty close to the $800 the model fetched when new, which is still a fraction the cost of a Leica or a top-of-the-line digital Nikon SLR. And it will use most Nikon-mount lenses made between 1977 and quite recently, when the company stopped including aperture rings on their SLR lenses.

I'd compare this rugged Nikon with modern versions of the Fender Stratocaster guitar, or a brand-new fountain pen: the FM3A looks superficially like something created decades earlier, and works pretty much that way too, but it has some clever modern enhancements that smooth the way for enthusiasts or professionals to use it elegantly. It's neat that Nikon ever decided to create it, and like the still-manufactured Nikon F6 film SLR, it's probably among the last of its kind.

Labels: film, geekery, history, nikon, photography

19 October 2009

Links of interest (2009-10-19):

From my Twitter stream:

- My dad had cataract surgery, and now that eye has perfect vision—he no longer needs a corrective lens for it for distance (which, as an amateur astronomer, he likes a lot).

- Darren's Happy Jellyfish (bigger version) is my new desktop picture.

- Ten minutes of mesmerizing super-slo-mo footage of bullets slamming into various substances, with groovy bongo-laden soundtrack.

- SOLD! Sorry if you missed out.

I have a couple of 4th-generation iPod nanos for sale, if you're interested. - Great backgrounder on the 2009 H1N1 flu virus—if you're at all confused about it, give this a read.

- The new Nikon D3s professional digital SLR camera has a high-gain maximum light sensitivity of ISO—102,400. By contrast, when I started taking photos seriously in the 1980s, ISO—1000 film was considered high-speed. The D3s can get the same exposure with 100 times less light, while producing perfectly acceptable, if grainy, results.

- Nice summary of how content-industry paranoia about technology has been wrong for 100 years.

- The Obama Nobel Prize makes perfect sense now.

- I like these funky fabric camera straps (via Ken Rockwell).

- I briefly appear on CBC's "Spark" radio show again this week.

- Here's a gorilla being examined in the same type of CT scan machine I use every couple of months. More amazing, though, is the mummified baby woolly mammoth. Wow.

- As I discovered a few months ago, in Canada you can use iTunes gift cards to buy music, but not iPhone apps. Apple originally claimed that was comply with Canadian regulations, but it seems that's not so—it's just a weird and inexplicable Apple policy. (Gift cards work fine for app purchases in the U.S.A.)

- We've released the 75th episode of Inside Home Recording.

- These signs from The Simpsons are indeed clever, #1 in particular.

- Since I so rarely post cute animal videos, you'd better believe that this one is a doozy (via Douglas Coupland, who I wouldn't expect to post it either).

- If you're a link spammer, Danny Sullivan is quite right to say that you have no manners or morals, and you suck.

- "Lock the Taskbar" reminds me of Joe Cocker, translated.

- A nice long interview with Scott Buckwald, propmaster for Mad Men.

Labels: animals, apple, biology, cartoon, geekery, humour, insidehomerecording, iphone, ipod, itunes, linksofinterest, nikon, photography, politics, science, surgery, television, video, web

13 September 2009

It looks like Leica is back, finally

Back in the early 20th century, Leica cameras were the first to make 35 mm film practical for still photography (instead of movies). For decades, they defined well made, technically innovative photographic tools. But since the autofocus and digital revolutions of the 1980s and 2000s, Leica seemed to lose its way. Though the company made partnerships with Minolta and, more recently, Panasonic—repackaging Panasonic cameras as Leicas with a few cosmetic and firmware changes, and charging a lot more money for the name—its flagship German-made SLR and rangefinder cameras fell behind the rest of the industry.

Back in the early 20th century, Leica cameras were the first to make 35 mm film practical for still photography (instead of movies). For decades, they defined well made, technically innovative photographic tools. But since the autofocus and digital revolutions of the 1980s and 2000s, Leica seemed to lose its way. Though the company made partnerships with Minolta and, more recently, Panasonic—repackaging Panasonic cameras as Leicas with a few cosmetic and firmware changes, and charging a lot more money for the name—its flagship German-made SLR and rangefinder cameras fell behind the rest of the industry.

Some professionals continued to use Leica cameras, mostly because of the superb lenses, but among amateurs and enthusiasts, the brand became more of a cult, with its extremely high-priced cameras and lenses fetishized by collectors, but used less and less by regular people taking pictures. In 1982, Leicas were the official cameras taken by the first Canadian expedition to reach the summit of Mt. Everest. Almost 30 years later, it would be hard to imagine such an expedition making a similar choice.

Yes, today's popular cameras (amateur and professional) include a lot of what the Leica Man would call superfluous. But even hard-core photographers—or especially them—now demand autofocus, intelligent computerized exposure metering, and state-of-the-art digital capture. Leica, in contrast to Japanese latecomers like Canon, Nikon, and even Sony, could offer none of these things. Technically, Leica's bulletproof M-series rangefinders were stuck in the '60s, and their R-series SLRs in the '70s. For the huge amounts of money Leica charged, their digital offerings like the crop-frame M8 rangefinder and Modul R digital back seemed (quite literally for the Modul R) like bolt-on afterthoughts.

But this week, Leica introduced these:

They are the new Leica X1 compact camera ($2000 USD), M9 full-frame digital rangefinder ($7000 USD), and S2 medium-format digital SLR ($22,000 USD). (The X1 and M9 are just announced; the S2 first appeared last year, but only now is getting near release, with an actual price.)

No, I did not accidentally add an extra zero to those prices. Leicas remain among the most expensive still cameras available to those outside the military, space programs, and specialized technical and scientific fields. Their lenses, if you can believe it, are even more upscale and (many say) of unsurpassed quality. For the M series rangefinder cameras, a "low end" f/2 Summicron 50 mm is $2000 USD, while its big brother, the top-of-the-line f/0.95 super–low-light Noctilux 50 mm is $10,000 USD. The S-series lenses start at $4500.

And yet, for once, these cameras are unique and innovative. All three are assembled in Germany, to start. The X1 is probably still overpriced, but it does include a genuine Leica lens and an unusually large (and thus low-noise) sensor for a compact camera. The M9 is, for many aficionados, the holy grail they've been waiting for since digital cameras became mainstream: a Leica rangefinder, of the same dimensions and metallic heft of its predecessors, fully compatible with nearly every Leica M lens made since 1954, yet with a full-frame 18-megapixel digital sensor like those in high-end digital SLRs.

The S2, while well out of reach of any normal photographer (even those who might consider an M9), is the really unusual one: Leica's first real foray into medium-format photography. The sensor is more than 50% larger than a full-frame 35 mm chip, but the camera itself is similar in size to Canon's smaller-sensored 1D and 1Ds Mark III and Nikon's D3 and D3x cameras, and has a much simpler interface than other modern DSLRs.

The S-series lenses are huge and heavy, but until now (with the marginal exception of the Mamiya ZD), digital medium-format photography hasn't had the convenience of autofocus SLR handling and simplicity. From the initial quick impressions of people who've tried it, Leica may have created a winner for high-end studio and landscape photographers in the S2. And, for the first time in many years, Leica has a truly modern camera that no one else can match. For now.

Labels: canon, geekery, leica, nikon, photography, sony

10 September 2009

A few short movies by me

I made three short videos a little while ago, but forgot to link them up here. Silly me. Here they are:

All three were taken with my Nikon D90 SLR, which has a video mode.

Labels: animals, conferences, gnomedex, meetup, nikon, seattle, transportation, video, whistler

10 August 2009

More luscious black and white

It's partly because of the look of using a larger frame of film, partly the texture it imbues, and partly because I'm just more careful when using an expendable resource, but as I've mentioned before, I get more keeper photographs when I shoot with black and white film than when I use my digital SLR. These are from a couple of recent rolls:

I didn't have to go far to get them either—I took all these pictures either in our house, in the yard, or at my kids' school up the street, all with natural light and no flashes or reflectors. I'm certainly not regretting my purchase of that used Nikon F4 or macro lens last year.

Time to pick up another roll or two of B&W, I think. I've run out for now.

Labels: film, geekery, nikon, photography

18 March 2009

Camera Works: image stabilization (VR, IS, and SR)

I just acquired my first stabilized camera lens, and I'm impressed so far, especially because it didn't cost me anything. Here's the story.

I just acquired my first stabilized camera lens, and I'm impressed so far, especially because it didn't cost me anything. Here's the story.

Sent for service

Last year I had my relatively new Nikon 18-135 mm zoom lens (designed for the D80 SLR, but bought for my D50) repaired under warranty, after the autofocus became unreliable and the lens housing felt loose. Unfortunately, Nikon's low-end lenses don't seem to stand up especially well to the usual wear and tear of enthusiastic use, because recently I had the same problem again with the same lens: unreliable autofocus and loose feel with the lens mounted on my camera, less than a year after the repair.

(By the way, I have a couple of much older but higher-end Nikon lenses that continue to work flawlessly despite their advanced age and considerable use. The problem is either with the company's more cheaply made lenses or with the particular one I owned.)

Anyway, the lens is covered by Nikon's excellent five-year warranty. So once I sent the zoom in for its second repair, Nikon had a look at it and decided to send me a replacement instead: the newer 18-105 mm VR zoom, introduced with the new D90 SLR a few months ago. While it doesn't zoom in quite as far, the newer lens includes Nikon's vibration reduction system—that's what the VR stands for.

What is vibration reduction?

What Nikon calls vibration reduction (VR), other camera makers call image stabilization (IS) or shake reduction (SR).They're all the same thing. Vibration reduction is a new technology, emerging in commercially available optical devices only in the last ten years. It can be built into the lens (as Nikon and Canon do) or the camera body (as Sony and Pentax do), but both work basically the same way: motion sensors detect the tiny shaky movements you make when hand-holding a camera and compensate for them by moving lens elements (Nikon, Canon) or the camera sensor (Sony, Pentax) with tiny motors.

At slow shutter speeds or long focal lengths, that reduces shake-induced blur in your photos. The technology doesn't make moving subjects (people, vehicles, animals) less blurry, because it can only compensate for things that make the camera vibrate.

The results

But within its limitations, VR works quite well. Take a look:

When using VR, looking through the viewfinder can be a bit strange, because the image you see is steadier than your hands. It's even more noticeable on my dad's image-stabilized binoculars, which magnify the image quite a bit more than my zoom lens, and stabilize both eyepieces. You can feel your hands shaking quite a bit as you look through them, but the image moves in a much more "damped" manner.

The result is great, because both in a camera and through binoculars, you can see more clearly when VR is on. And when you take photos of stationary subjects, you can shoot with shutter speeds one or two stops slower (i.e. taking in only 25% as much light, maybe even less) and still get decently sharp pictures.

It's not the same as having a lens with a wider maximum aperture, or a camera with better low-light sensitivity (ISO), but it's another tool to help make better images.

Labels: cameraworks, geekery, nikon, photography, repairs

16 March 2009

A little walk

This is my kids' walk to school—and since I attended the same school in the '70s, it's also the same walk I took each day 30 years ago:

Compiled from 47 photos taken with my Nikon D50 every 15 to 20 steps on the way, and made with iMovie '09. Music is my tune "Camp Walk," from 2006.

Labels: family, memories, movie, nikon, penmachinepodcast, school

07 January 2009

Are there perhaps too many digital SLRs on the market?

One way to get lots of people to see a photo of yours on the image sharing site Flickr is to take a good picture. That requires talent, skill, and dedication. A few of my pictures have become popular simply because they're good photographs—at least I think so.

But my most popular pictures on Flickr aren't like that at all. They're nerdy: pictures of wacky guitars or geek conferences, of old computers or Linux running on a Mac.

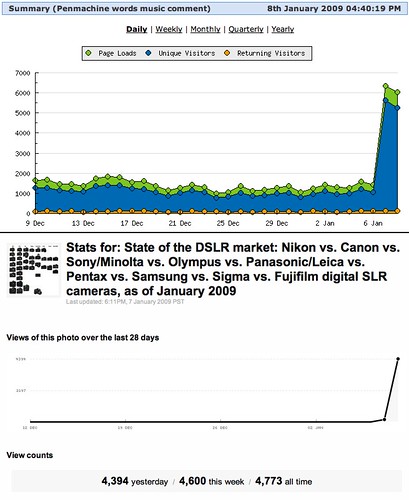

And what do you do to attract huge numbers of viewers and comments and favourites? Simple, go full nerd: just make a picture of a whole bunch of cameras and encourage people to argue about them. More than 38,000 views in six months, 208 favourite votes, and dozens and dozens of comments:

Old image of almost 25 cameras

State of the DSLR market - June 2008 (old)

An earlier attempt of mine at the same thing even had commenters threatening to kill each other about the kind of camera they like! But my favourite comment was from Axl Van Goks: "I like the black one with the buttons and stuff."

Since the digital camera market changes like crazy, my big collage from June 2008 was out of date within weeks. I waited for all the pre-Christmas camera introductions to shake out, and now I've made a new version that includes all the current digital SLR cameras I could find (almost 40) from Nikon, Canon, Sony, Olympus, Pentax, Panasonic, Leica, Samsung, Sigma, and Fujifilm:

New image of almost 40 cameras

State of the DSLR market - January 2009 (new)

I expect the arguing to begin soon in the comments. The picture has 139 views and 4 favourites since I posted it three and a half hours ago. And yes, yes, I know, I know: they're not all strictly SLRs, but I think they're all of interest to SLR buyers.

Ah, art. Have at it.

UPDATE: My thesis appears to be correct. As a rule of thumb, the more cameras you put in a picture on Flickr, the more popular it is:

Links from John Gruber and 37signals didn't hurt either.

Labels: canon, controversy, flickr, geekery, leica, linkbait, nikon, olympus, panasonic, pentax, photography, sony

28 December 2008

Wasted megapixels

I like what the team at Digital Photography Review have to say about the world of digital SLR cameras (my emphasis below):

I like what the team at Digital Photography Review have to say about the world of digital SLR cameras (my emphasis below):

...the biggest issue facing manufacturers today [is that] ever-increasing sensor resolutions are simply not being backed up by lenses capable of delivering enough detail, [so what are] all those extra megapixels [...] supposed to achieve (other than take up storage space and slow the camera down). [...] we'd rather see manufacturers directing their R&D resources towards improving sensor efficiency, to give reduced noise and increased dynamic range, rather than continuing the megapixel marketing mania.

What Andy Westlake is saying is that, especially for the crop-sensor DSLR cameras most people buy, even the best lenses that Nikon, Canon, Zeiss, Leica, and others make don't provide enough resolution to take full advantage of all the megapixels packed onto the sensors in the cameras they connect to. Certainly the inexpensive lenses that most DSLRs come with don't do that.

For a long time, I used my 2006-era Nikon D50, which has "only" a 6-megapixel sensor, in reduced-resolution mode, taking pictures that were a bit over 3 megapixels. They were big and detailed enough for me as an amateur photo enthusiast, but I eventually moved up to the full 6 MP resolution when I got a bigger hard drive and didn't mind the extra room that larger files sucked up. So while I lust after the improved low-light performance and faster burst modes of newer cameras like the D90 and D300, their increased resolution on the same size sensor actually turns me off a bit, because of the extra storage I'll need for the images. (They do have reduced-resolution 6.9 MP and 3 MP modes, however.)

It is true that a 12-megapixel crop-sensor DSLR still gives you a significant real resolution advantage—when using quality lenses. But pushing up to 15 MP and beyond, as crop-sensor DSLRs are starting to do, seems to be going further than what our lenses are capable of. (As DPReview notes, that won't happen for full-frame DSLRs until they get into the 38-megapixel range, which I expect in the next couple of years.) In the point-and-shoot market, with even smaller sensors and smaller, lower-quality lenses, the problem is worse.

Until recently, Nikon has generally resisted the more-more-more megapixels bandwagon with their DSLRs—more so than Canon, Sony, and others—and emphasized performance instead. But I wish all of them would look at the example of Panasonic's recent DMC-LX3 point-and-shoot: "Other cameras offer more pixels, more zoom, and bigger LCDs," says review Jeff Keller, "[but it] does deliver very good quality images for a compact camera."

That's what we photographers really want, isn't it? Good pictures? Especially if we're paying for megapixels that out-resolve our lenses, and are therefore largely going to waste!

Labels: controversy, geekery, nikon, panasonic, photography

28 November 2008

Practical extravagance

If money were no object, I wouldn't be one to buy a fancy car or a mansion—I'd get something good in each case, but also something practical. It's the same with cameras.

If money were no object, I wouldn't be one to buy a fancy car or a mansion—I'd get something good in each case, but also something practical. It's the same with cameras.

I've used Nikon's top-end D3, and it's a fine instrument, but far more camera than I'd need. The D3x, just mistakenly announced today, would be even further overkill. Never mind the various medium format cameras and the upcoming ultra-luxe Leica S2.

So, if I were suddenly independently wealthy, I'd still get myself a new Nikon, but it would be the D700, which packs most of the power of the D3, including its wonderful low-noise, high-sensitivity full-frame sensor, into a smaller (we're talking relatively smaller here) package. I've also tried the similarly sized D300, so I think the D700 would fit better in my hand.

And I'd buy some great lenses too, of course, because that's where money is best worth spending. I'm still using an inexpensive but quality lens I bought in 1995, while the camera it went with is long, long gone.

Finally, I'd travel to beautiful places with my family, to make photos with them.

Labels: gadgets, money, nikon, photography, travel

01 October 2008

I'm interviewed about film photography

Last week fellow Canadian podcaster John Meadows, whose show is called "On the Log," interviewed me about my recent return to dabbling in film photography.

Last week fellow Canadian podcaster John Meadows, whose show is called "On the Log," interviewed me about my recent return to dabbling in film photography.

John's episode 38 (MP3 file) is titled "Film at 11." I talk about how I now approach making black and white pictures, as well as the cross-processed colour photographs I've taken in the past couple of months. Plus John and I discuss other differences between film and digital photography for archiving and backup.

The podcast is a good corollary to my recent talk at Vancouver's PhotoCamp and my Camera Works series here on the blog.

Labels: film, geekery, nikon, photography, podcast

30 September 2008

My black and whites are more popular

Since I started taking black and white film photos again back in July, I've noticed something. People like them a lot, on average more than my other pictures.

I'm not sure if it's that I take these photographs differently, because I know they are single shots on a limited medium, and will lack colour, so I compose and shoot them more carefully than others.

Or perhaps it's just that they are striking purely because they don't have colour and people aren't used to that anymore, epecially online. Maybe if I converted some of my other pictures to B&W, they might get a similar response too.

I know I enjoy making those images. It's pricey compared to digital photography, but that's part of what makes them different too.

Labels: film, friends, geekery, nikon, photography

04 September 2008

Up to ten thousand

It's not exactly a brilliant piece of photographic art, but it is pretty funny: this is the 10,000th picture taken with my Nikon D50 digital camera since I got it pretty much exactly two years ago. I didn't even take the photo, which is of "Bongo Neurotic," who was playing percussion with us yesterday; guitar player Sean borrowed my camera to snap it.

It's not exactly a brilliant piece of photographic art, but it is pretty funny: this is the 10,000th picture taken with my Nikon D50 digital camera since I got it pretty much exactly two years ago. I didn't even take the photo, which is of "Bongo Neurotic," who was playing percussion with us yesterday; guitar player Sean borrowed my camera to snap it.

To reach 10,000 photos in two years is around 13.7 photos per day, on average, every day. Every. Single. Day. So while I like my film camera too, I'm glad I haven't had to pay for a roll of film (plus processing and printing) every day or two during that time.

Interestingly, the shutters on modern DSLR cameras are often tested for 100,000 or 150,000 or even 300,000 actuations—at my current rate, I'd have to keep going for between 10 and 30 years before the shutter wears out. I expect I'll probably replace the camera a few times in that span, assuming I even live that long.

Labels: anniversary, band, nikon, photography

01 September 2008

Links of interest (2008-09-01):

- It's a fact: I find it astonishing that the governor of Alaska (Alaska!), and new vice-presidential running mate for John McCain, doesn't think that climate change is human-generated. I'm guessing her house isn't built on melting permafrost.

- I'll let Dan Savage give his trademark trenchant take on the other Sarah Palin news.

- This past week Canon introduced its new EOS 50D SLR (a nice upgrade from the 40D), and Nikon followed with its D90 (which supersedes the D80 and takes movies, a first for an SLR camera). While I use Nikon myself, and the D90 would be great if I needed a new camera, for people just getting into the market, I still think the Pentax K200D is an excellent deal.

- Speaking of photography, the always-snarky Ken Rockwell has (as usual) excellent advice on how to carry less stuff so you make better pictures. I should have heeded his advice when I went up Whistler mountain a few weeks ago. I took a bunch of photos, but only used one lens, even though I schlepped a whole bag's worth of stuff (plus a tripod I never unfolded) up there—just like the guys Ken was making fun of at the zoo.

- I'm a little too old to have ever been all that interested in going to Burning Man, but I'm particularly glad to have avoided this year's dust storm. Yuck.

- Looks like Americans won't be the only ones having an election this fall.

Labels: canon, environment, linksofinterest, nikon, pentax, photography, politics

18 August 2008

Photo gearheaddery from Sigma, Canon, and DPReview

Photo buffs (yeah, like me) will be interested to read two new gear reviews at DPReview today:

Photo buffs (yeah, like me) will be interested to read two new gear reviews at DPReview today:

- Sigma's new 50 mm f/1.4 lens is unusual: the first genuinely modern 50 mm lens design in a long time, not from one of the camera manufacturers, and both huge and expensive compared to lenses made by Canon, Nikon, and Pentax (whose comparable lens is half the weight and price!).

- Canon's $8000 EOS 1Ds Mark III is the top of the heap for price and resolution among digital SLR cameras. It's taken awhile for DPR to review it, but it's interesting to see how it compares to Nikon's very different top model, the D3.

Labels: canon, nikon, photography, review, sigma

28 July 2008

My slightly lazy choices for black and white film

Black and white photos make for compelling images, because they are inherently unrealistic, without any colour information, so you look at them differently. And as a photographer, you create them differently, with different composition and exposure, if you know they will be black and white in the end.

Black and white photos make for compelling images, because they are inherently unrealistic, without any colour information, so you look at them differently. And as a photographer, you create them differently, with different composition and exposure, if you know they will be black and white in the end.

There are numerous ways to create excellent B&W (or, to be accurate, greyscale) images from colour digital originals using Photoshop or similar software tools—but there is still something to be said for black and white film photography.

When I first got into photography in the 1980s, and when I didn't plan to process and print the film myself, I would use Ilford's XP2 film for black and white, because unlike most B&W films, any regular colour photo lab could process it using their automated C-41 chemical machines. And I found myself a roll of XP2 for the first set of photos I took with the Nikon F4 film camera I bought recently.

What I didn't know is that the two big film manufacturers, Kodak and Fuji, also make similar chromogenic black and white films that can be processed using C-41: BW400CN and Neopan 400 CN respectively. I don't know when those were introduced, but I don't think they were around 20 years ago along with Ilford. I also discovered that many local photo retailers (even non-specialist, non-pro stores) carry at least one of the three—London Drugs has triple-packs of Kodak BW400CN for a reasonable $4 or so per roll, for instance.

What I didn't know is that the two big film manufacturers, Kodak and Fuji, also make similar chromogenic black and white films that can be processed using C-41: BW400CN and Neopan 400 CN respectively. I don't know when those were introduced, but I don't think they were around 20 years ago along with Ilford. I also discovered that many local photo retailers (even non-specialist, non-pro stores) carry at least one of the three—London Drugs has triple-packs of Kodak BW400CN for a reasonable $4 or so per roll, for instance.

While I've tried cross processing of slide film pictures taken with the F4 camera recently, and the wacky colours there are fun, I think I'll be spending most of my film shooting time in black and white. I'll see whether I prefer the Ilford or Kodak (and maybe Fuji) stocks when I do.

While I've tried cross processing of slide film pictures taken with the F4 camera recently, and the wacky colours there are fun, I think I'll be spending most of my film shooting time in black and white. I'll see whether I prefer the Ilford or Kodak (and maybe Fuji) stocks when I do.

Yes, I may try some traditional black and white silver halide film (which requires different processing), but the C-41 black and whites are just so easy to take it to the local supermarket for one-hour processing, printing, and scanning to CD. It's almost like the instant gratification we're used to in the digital era. Or as close as I can get while still using film anyway.

Labels: film, geekery, nikon, photography

12 July 2008

First roll

I said I'd show you the first photos with my new/old Nikon F4 film camera. Here they are. Just for extra retro appeal, my first roll of film was black and white, using an expired roll of Ilford XP2 film:

I took all of them with a single fixed-length prime lens, my Nikkor 50 mm f/1.8, the kind of lens all cameras used to come with.

P.S., I told you the camera was big. But it really is a marvel of electromechanical engineering—the promo materials say it has more than 1700 parts, including the clever tiny LCD and LED panels inside the camera body showing exposure information.

I'm sure modern cameras have a variety of equally interesting stuff, but what's cool about the F4 is that it's designed to be disassembled so you can actually get at the guts. The focusing screen, shutter, mirror, film winding mechanism, and so on are all easily visible, so it's much easier to understand what the camera is doing when you take a picture.

Labels: film, geekery, nikon, photography

09 July 2008

The monster film camera arrives

Yesterday I got an online notice that my eBay purchase Nikon F4 film camera had cleared Canada Customs. I thought that might mean it would take a few more days to arrive, but the Canada Post truck showed up with it this afternoon. I made some camera nerd unboxing photos with my digital SLR if you'd like to see them.

Yesterday I got an online notice that my eBay purchase Nikon F4 film camera had cleared Canada Customs. I thought that might mean it would take a few more days to arrive, but the Canada Post truck showed up with it this afternoon. I made some camera nerd unboxing photos with my digital SLR if you'd like to see them.

I have to say this: wow. For a 20-year-old design, the F4 is an amazing camera. It weighs a ton, because it's both huge (freakin' huge) and made of thick metal under the rubber covering, but it feels great in my hands. It's remarkably responsive, easy to figure out for anyone who grew up with the dials, knobs, and buttons of an analog SLR, and fast.

I'd also forgotten what it's like to look into a bright, full-frame, 100%-coverage viewfinder with minimal clutter. Compared to the finder view in my D50, it's expansive, and having only one central autofocus point plus a couple of etched circles (to show where the different types of light metering act) means there's a lot less other stuff busying up the view.

All my Nikon-mount lenses fit and work—even ones with technology designed more than a decade after the camera ceased production—although the newest, designed for a smaller digital sensor and lacking an aperture ring, is limited and vignettes heavily. Most surprising, my SB-600 flash functions pretty much fully, including reading lens focal length, working with through-the-lens (TTL) metering, and acting as an autofocus illuminator (which the camera otherwise lacks).

Running the motor drive at top speed yields a full paparazzi kssht-kssht-kssht-kssht-kssht, much faster than my lower-end D50 digital SLR from 2006. Autofocus is surprisingly quick too, though not up to complete modern standards. Unlike my D50, the F4 has mirror lockup, dedicated buttons for exposure and focus lock, depth of field preview, and an eyepiece shutter on a removable viewfinder pentaprism.

I loaded the F4 up with some Ilford black-and-white film and took it along while my younger daughter and I walked to the store and the park this sunny afternoon. I also picked up a new camera strap at Kerrisdale Cameras, since none of my current ones have the keychain-style metal rings at the ends that work with the F4's teeny tiny metal strap connectors. And I'll have to track down a rubber eyepiece ring, since that's the only stock item missing from the camera.

Of course, the key frustration with any film camera is that you can't see your pictures right away—I'll have to wait to finish the roll and get it processed, just like I did my entire picture-taking life from childhood until I bought my first digital camera in 2002. And yet that also forces me to think a bit more: How will this look in black and white (for this roll)? What's the best angle for this shot (I can't waste film trying a bunch of different ones)? What works in this light at this film ISO setting (since I can't adjust that)? What kind of depth of field and shutter speed do I want? And so on.

Perhaps the greatest pleasure comes from something I haven't had in more than 15 years: an SLR camera with analog controls for every feature, not multifunction digital buttons and mode dials and four-way controllers and LCD screens. Other than the lack of a manual film winding lever, and the info LCD inside the viewfinder, the F4 has the same kind of excellent tactile controls and analog displays photographers relied on for decades, from the first Leica rangefinder shooters to the astronauts walking on the moon.

There's definitely a difference adjusting the lens opening with an aperture ring on the lens, and the shutter speed with a dedicated dial on the top of the camera, than with the one or two thumbwheels on the handgrips of modern digital (and even film) SLRs. In the digital era, only the otherwise imperfect Panasonic Lumix DMC-L1 and Leica M8, with their retro aesthetic, offer anything like that.

Obviously, I don't have any of my photos from the F4 yet. But I'll link them up when I do.

Labels: film, gadgets, geekery, leica, moon, nikon, photography