Penmachine

07 November 2009

The end of the Wall

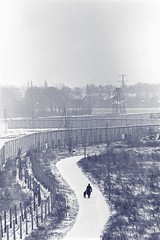

When I saw the footage of people hammering away at the Berlin Wall 20 years ago, I cried. I've never been there (the closest I came was Frankfurt Airport, three years earlier), but it's where my dad was born in 1939. Berlin has always loomed large in my family's history—through stories from him and my aunt, from my grandmother and step-grandfather, of the War, and the Blockade. And in the phone calls and letters to and from the city, where we still have relatives.

When I saw the footage of people hammering away at the Berlin Wall 20 years ago, I cried. I've never been there (the closest I came was Frankfurt Airport, three years earlier), but it's where my dad was born in 1939. Berlin has always loomed large in my family's history—through stories from him and my aunt, from my grandmother and step-grandfather, of the War, and the Blockade. And in the phone calls and letters to and from the city, where we still have relatives.

Berlin is where my grandfather Karl, my father's father, died in 1947. Thin and weakened in a Russian PoW camp, he returned to his family when the War ended, but never regained his full health. In the ravaged city, medical care wasn't quite good enough, or medicine available enough, to save him when he caught an infection—perhaps pleurisy, perhaps something else. With modern antibiotics and intensive care, he would probably have lived. And I would almost certainly never have been born.

My parents will be in Berlin again this week, able to cross back and forth across the city. The Wall is only shards now, the city and Germany itself now whole, if sometimes awkwardly. I visited Moscow and what was then Leningrad in 1985, while Russia was still fully Communist, though waning. Where today there are billboards, then the signs were only massive revolutionary slogans. To my children, the Cold War is history, long gone before they were born.

But it's not really gone. Current events emerge from what happened then. And my father told me that, a few years ago when he visited the village in the former East Germany to which he'd been evacuated late in the War, the buildings still had bullet holes in the walls.

Labels: anniversary, europe, family, history, war

04 November 2009

Family and flight

Today my parents flew to Frankfurt for a couple of weeks in Germany. They're staying with friends in Bad Zwischenahn, as well as visiting some of my father's relatives in Berlin, where he was born and lived until 1955. They had enough airline points to travel First Class, which I don't think they've ever done before.

Today my parents flew to Frankfurt for a couple of weeks in Germany. They're staying with friends in Bad Zwischenahn, as well as visiting some of my father's relatives in Berlin, where he was born and lived until 1955. They had enough airline points to travel First Class, which I don't think they've ever done before.

Their trip is shorter than they had initially planned. My parents live next door to us in our duplex, the same house where I grew up, and they offer us a lot of support, especially with the kids, and particularly since I've been ill over the past few years. I told them a few weeks ago that their initial trip seemed too long to me. It was hard to admit that—I'm 40 years old and don't like having to depend on my parents again.

Yet it wouldn't have been fair not to ask. I have a lot of side effects from the cancer medications these days, and while we can handle not having my mom and dad nearby for a week or two, longer than that is likely to put a lot of pressure on my wife, and my daughters, when I'm not feeling well.

The three of us, Mom, Dad, and I, drove to the airport today, and had a fancy lunch in the Fairmont Hotel overlooking the jetway. I dropped them at the gate, then walked around the airport a bit and watched the planes some more. Then I drove home and spent an hour in the bathroom, as happens these days.

I'm sure they'll have a fun trip, and I'm glad they could go. I'll be happy to pick them up when they return too.

Labels: airport, cancer, europe, family, travel

01 March 2009

Deep bathtubs and the sound of surf

I still have some more photos to upload, but early this evening we got back home after seven and a half hours and nearly 300 km by car and ferry returning from Tofino and Parksville. It was a great trip, one that will leave memories. As a nice capper, we managed to meet up with my friend Simon on the ferry in Nanaimo and, once we crossed the water, gave him a ride into West Vancouver to visit his family.

I still have some more photos to upload, but early this evening we got back home after seven and a half hours and nearly 300 km by car and ferry returning from Tofino and Parksville. It was a great trip, one that will leave memories. As a nice capper, we managed to meet up with my friend Simon on the ferry in Nanaimo and, once we crossed the water, gave him a ride into West Vancouver to visit his family.

We live in a huge part of the world. I mean huge oceans, huge mountains, huge trees, huge birds, huge beaches, and huge distances. At highway speeds (except for the really twisty parts, and lunch), it took us three hours to drive in the rain about half the way, across one of the narrowest parts of Vancouver Island. It's apparently a faster trip right across Ireland. We passed between snow-blanketed mountains 1400 m high—taller than any in Britain, to make another cross-Atlantic island comparison.

It's common for us British Columbians to take day trips or short vacations over distances that would cross several countries in Europe, as my family did this week. I'm glad to be home, but as I noted on on Twitter, I miss the huge, deep, comfortable hotel bathtubs. And the heated tile floor in Tofino. And the sound of surf, gentle or roaring.

Labels: animals, canada, europe, family, friends, memories, oceans, travel

05 February 2009

The big gap

For the past couple of weeks I've been reading God's Crucible

For the past couple of weeks I've been reading God's Crucible, a history book by David Levering Lewis—which I gave to my dad for Christmas, but which he's loaned back to me. Today I got a lot of reading done, because my body was screwing with me: I'll have to skip my cancer medications for the next day or two because the intestinal side effects, unusually, lasted all day today and into the night, and I have to give my digestive system (and my butt) a rest.

Lewis's book covers, at its core, a 650-year span from the 500s to the 1200s, during which Islam began, and rapidly spread the influence of its caliphate from Arabia across a big swath of Eurasia and northern Africa, while what had been the Roman Empire simultaneously fragmented into its Middle Ages in Europe. That's a time I've known little about until now.

The history I took in school and at university covered lots of things, from ancient Egypt and Babylon up to the Roman Empire, and from the Renaissance to the 20th century, as well as medieval England. I learned something about the history of China and India, as well as about the pre-Columbian Americas. But pre-Renaissance Europe and the simultaneous rapid expansion of the dar al-Islam are a particularly big gap for me.

Whose Dark Ages?

I knew a little about Moorish Spain, and a tad about Charlemagne and Constantinople, but otherwise it was just the Dark Ages for me, and for a lot of students who learned the typical Eurocentric view of history. There was much more going on in more populated and interesting parts of the world, though. While Europeans (not even yet named that) eked along with essentially no currency, trade, or much cultural exchange beyond warfare with horses, swords, and arrows:

- China went through the Sui, Tang, and Song dynasties, reaching the peak of classical Chinese art, culture, and technology.

- India also saw several dynasties and empires, as well as its own Muslim sultans.

- Large kingdoms of the Sahel in near-equatorial Africa arose, including those of Ghana, Takrur, Malinke, and Songhai.

- The Maya in Central America developed city-states and the only detailed written language in the Western Hemisphere.

- The seafaring Polynesians reached their most distant Pacific outposts, including Easter Island, Hawaii, and New Zealand.

Crucially important, of course, was Islam. Muhammad was born in the year 570, and shortly after he died about six decades later, Muslim armies exploded out of Arabia and conquered much of the Middle East and North Africa, then expanded east and north into Central Asia. By the early 700s, the influence of the caliphate headquartered in Damascus had reached Spain (al-Andalus), where Muslims would remain in power for 700 years.

In his book, Lewis flies through the origins of Islam, the foundations of the Byzantine and Roman branches of the Catholic Church after the fall of Rome, the interminable conflict between it and Zoroastrian Persia to the east, the Muslim caliphate's sudden rise up the middle to take over the eastern and southern Mediterranean, and the crossing of Islamic armies into Europe at Jebel Tariq (now called Gibraltar) in 711. Then things bog down a little.

I'm about half-way through the book, and Lewis throws out so many names, alternate names for the same people, events, places, and such that it's hard to keep up. He hops back and forth in time enough that what story he's trying to tell isn't always clear—he was won the Pulitzer Prize, but that was for more focused historical biographies, such as of W.E.B. Du Bois, rather than sweeping surveys like this one. His writing isn't overly complex, and I'm learning a lot, but it's a tough go sometimes. Still, I think it will be worth sticking it out.

Labels: books, europe, history, religion, review

20 November 2008

Berlin 1965

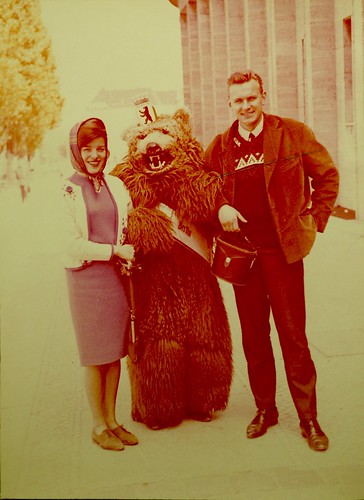

For as long as I can remember, my parents have had this photo hanging on their bedroom wall:

I made a copy last night because my younger daughter has a project at school where she's discussing Germany, and she wanted a copy of this picture to illustrate Berlin, where it was taken. It was 1965, on my parents' honeymoon. My mom and dad were 26 at the time, and that's the city's mascot, a bear, between them. Here they are today (without the bear):

My dad still wears collared shirts most of the time, though my mom isn't into the bonnets anymore.

They look young in that first photo. My wife and I were the same age, 26, when we got married 30 years later. We didn't feel so young then, but we were too.

Labels: anniversary, europe, family, photography, school

07 October 2008

London this morning

When I was a kid, financial news was perhaps the most boring thing in the whole world, except maybe the TV farm report that frustratingly preceded early-morning cartoons. (That farm news seems to have disappeared here in Vancouver. Even the telephone weather line I used to check, pre-web, before bicycling to university each day, no longer reports hay drying conditions in the summer.)

When I was a kid, financial news was perhaps the most boring thing in the whole world, except maybe the TV farm report that frustratingly preceded early-morning cartoons. (That farm news seems to have disappeared here in Vancouver. Even the telephone weather line I used to check, pre-web, before bicycling to university each day, no longer reports hay drying conditions in the summer.)

I can't say that my opinion of money and business news has changed much in the intervening decades. It's usually a snore-fest of inscrutable numbers, impenetrable market analysis, and a parade of old guys in dark suits and ties. (Yeah, I hire an accountant to sort out my taxes after my perfunctory sorting of income and expenses each year.) Despite the impacts of global markets on everyone's ability to get a job, buy things, use credit, and so on, it always seemed so disconnected from my daily life that I just couldn't get interested.

Well, these past few weeks have certainly removed world financial news from the "boring" category, but I still can't pretend to understand what's going on very well. If you're like me, I strongly recommend This American Life's recent audio episode "Another Frightening Show About the Economy." Before you listen to that, however, I suggest you check out its predecessor from May 2008, "The Giant Pool of Money," which dissects the American sub-prime mortgage disaster that preceded the current credit crisis.

Both shows do an amazing job of explaining terminology such as "commercial paper," "credit default swaps," "leverage," "financial instruments," and other stuff I never bothered to learn about, and of putting together the chain of insanity that led to today's bizarro state of affairs, where supposedly laissez-faire conservative governments around the world are desperately spending hundreds of billions of dollars to nationalize banks and insurance companies. Even if you work in the finance industry, are a savvy investor, or otherwise have a handle on this stuff, check out the two shows. You'll likely learn something anyway.

UPDATE: Here's an even more direct explanation (via Kottke).

Labels: americas, europe, money, news, podcast, politics

17 May 2008

It was acceptable in the eighties

Back in 1986, a group of kids from my all-boys' private school (St. George's School in Vancouver) and a couple of affiliated girls' schools (Crofton House and York House) took a Spring Break "art tour" trip to Italy, with whirlwind visits to Rome, Florence, Pisa, Venice, Turin, and so on.

I have photos in an album somewhere, but Anne Pewsey Richards, who was also on the trip, has done much better. She posted a bunch of pictures to Facebook, and gave me permission to repost them at Flickr. If you thought my glasses were big the year before in my geekiest photo, check them out here with the accompanying sunglass clip-ons:

Anne's group shot also includes some prime '80s hair and fashions. (I'm on the far right, squinting—shoulda worn the clip-ons.)

Finally, you can see that I was a camera nerd, with the Nikon, big zoom lens, and obnoxious camera strap, even then (again, I'm far right—guess I had the contact lenses on there):

I'm sure there was no way at all that local Italians could tell that we were tourists. There are several people in her photos (Anne included—but she noted that she's lived in England since the early '90s) whom I have not seen even once in the intervening 22 years.

I also haven't been back to Europe since this trip.

Labels: europe, friends, memories, photography, retro, school, travel

12 April 2008

Bomb days

A few days ago I wrote about the 50th anniversary of the Ripple Rock detonation, which sent me hunting around the Web for information. Inevitably, I came across lots of pictures of explosions of all sorts.

I think many people in a broad cohort around my age (38), who grew up during the Cold War, have a morbid fascination with photos of nuclear bomb tests. Some of them are chillingly, starkly, awfully beautiful, especially this set from the French Licorne ("Unicorn") test in the Pacific in 1970:

Reports say that the day of the Licorne detonation had "cloudy conditions but good visibility," but notice how the bomb's shockwave punches right through those clouds, sweeping them entirely away and leaving blue sky in the later pictures. Scary.

Of the hundreds of above-ground nuclear detonations by the U.S., the U.S.S.R., the U.K., France, and China between 1945 and 1980, no two seem to have looked the same. The photographs that freak me out the most are those where the surrounding landscape (and thus the scale) is clear. Or where soldiers walk towards a mushroom cloud in the Nevada desert.

China performed the last atmospheric test of a nuclear weapon almost 28 years ago—these sorts of photos are all, thankfully, now historical. But North Korea conducted what may have been a failed atomic explosion uderground as recently as 2006.

So those mushroom-cloud images don't worry me like they used to when I was a kid. But the worry isn't entirely gone either, is it?

Labels: age, americas, china, europe, history, korea, science, war